A bare-chested Viking offers a slave girl to a Persian merchant in an artist’s rendering of a scene from Bulgar, a trading town on the Volga River. Illustration by Tom Lovell, National Geographic Creative

New clues suggest slaves were vital to the Viking way of life—and argue against attempts to soften the raiders’ brutish reputation.

The ancient reputation of Vikings as bloodthirsty raiders on cold northern seas has undergone a radical change in recent decades. A kinder, gentler, and more fashionable Viking emerged.

But our view of the Norse may be about to alter course again as scholars turn their gaze to a segment of Viking society that has long remained in the shadows.

Archaeologists are using recent finds and analyses of previous discoveries—from iron collars in Ireland to possible plantation houses in Sweden—to illuminate the role of slavery in creating and maintaining the Viking way of life.

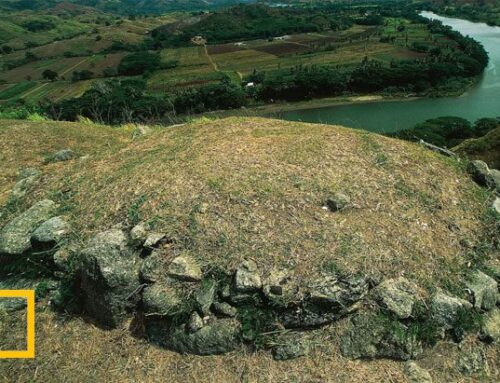

Small houses surround a great hall at a Viking site in Sweden called Sanda. Some archaeologists believe this may have been a Viking plantation with slaves as the labor force.

“This was a slave economy,” said Neil Price, an archaeologist at Sweden’s Uppsala University who spoke at a recent meeting that brought together archaeologists who study slavery and colonization. “Slavery has received hardly any attention in the past 30 years, but now we have opportunities using archaeological tools to change this.”

Scandinavian slavery still echoes in the English language today. The expression “to be held in thrall,” meaning to be under someone’s power, traces back to the Old Norse term for a slave: thrall.

Slavery in the region long predates the Vikings. There is evidence of vast economic disparity as early as the first century A.D., with some people living with animals in barns while others live nearby in large, prosperous homes. In 2009, archaeologist Frands Herschend at Uppsala detailed a burnt structure from this early era in which people and animals were immolated. The human bodies were left in the ruins rather than retrieved for burial.

Ancient chronicles long mentioned that people, as well as precious objects, were a target of the Viking raids that began in 793 A.D. at the Scottish monastery of Lindisfarne. The Annals of Ulster record “a great booty of women” taken in a raid near Dublin in 821 A.D., while the same account contends that 3,000 people were captured in a single attack a century later.

Ibn Hawqal, an Arab geographer, described a Viking slave trade in 977 A.D. that extended across the Mediterranean from Spain to Egypt. Others recorded that slaves from northern Europe were funneled from Scandinavia through Russia to Byzantium and Baghdad.

Shortage of Women and Workers

Price suspects that “slavery was a very significant motivator in raiding.” One key factor may have been a dire need for women.

Some scholars believe that the Vikings were a polygamous society that made it hard for non-elites to find brides. That may have driven the raids and ambitious exploration voyages for which Vikings are best known. Some genetic studies, for example, suggest that a majority of Icelandic women are related to Scottish and Irish ancestors who likely were raid booty.

As Viking fleets expanded, so did the need for wool to produce the sails necessary to power the ships. This also may have driven the need for slaves. “There was a significant shift in agriculture,” said Price. The pressing need for wool production likely led to a plantation-like economy, a topic now being studied by researchers.

Slavery was a very significant motivator in raiding.

Neil Price | Archaeologist

For example, at a Swedish site called Sanda, researchers in the 1990s found a great hall surrounded by small houses. Some Swedish archaeologists now believe this could have been a Viking plantation with slaves as the labor force.

“What you likely have is a slave-driven production of textiles,” said Price. “We can’t really know who is making the cloth, but the implications are clear.”

William Fitzhugh, an archaeologist at the Smithsonian Institution, added that “female slaves were concubines, cooks, and domestic workers.” Male thralls likely were involved in cutting trees, building ships, and rowing those vessels for their Viking masters.

Human Sacrifices

Other studies suggest that Viking slaves were sometimes sacrificed when their masters died, and they ate more poorly during their lives.

Elise Naumann, an archaeologist at the University of Oslo, recently discovered that decapitated bodies found in several Viking tombs likely were not related to the other remains. This lack of kinship, combined with signs of mistreatment, make it likely that they were slaves sacrificed at the death of their masters, a practice mentioned in Viking sagas and Arab chronicles.

The bones also revealed a diet based heavily on fish, while their masters dined more heartily on meat and dairy products.

The harsh treatment accorded slaves is amply recorded both in the archaeological and historical record.

The harsh treatment accorded slaves is amply recorded both in the archaeological and historical record. On the Isle of Man in the Irish Sea, a wealthy male Viking’s tomb includes the remains of a young female killed by a ferocious blow to the top of her head and mixed in with the ashes of cremated animals. Other such examples can be found across northern Europe.

Life for thralls was clearly harsh. A 14th-century poem—the original likely dates from the end of the Viking era—gives an idea of how Vikings saw their slaves. Among their names were Bastard, Sluggard, Stumpy, Stinker, and Lout.

Ahmad Ibn Fadlan, an Arab lawyer and diplomat from Baghdad who encountered the men of Scandinavia in his travels, wrote that Vikings treated their female chattel as sex slaves. If a slave died, he added, “they leave him there as food for the dogs and the birds.”

But one recent discovery challenges ideas about the status of slaves. In recent years, researchers have identified nearly 80 Viking skeletons that feature deep grooves across their upper front teeth. Some speculate that these may have been a mark of a warrior class, since the skeletons were all male.

Anna Kjellstrom at Stockholm University, noted that the remains of two men in central Sweden that appear to be buried as slaves include the teeth grooves.

“This is not the same as saying that modified teeth is a feature only found in slaves,” Kjellstrom added. But it is forcing scholars to rethink the idea that it was solely for warriors, as well as the place of slaves in Viking society.

Nevertheless, as scholars focus on the Norse need for human chattel, the kinder and gentler aura surrounding Vikings today may begin to diminish.