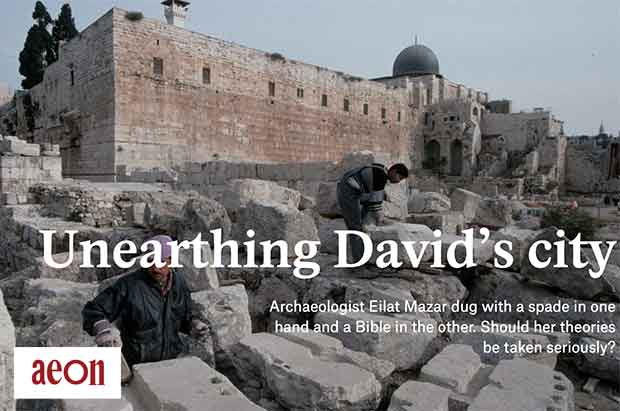

Archaeologist Eilat Mazar dug with a spade in one hand and a Bible in the other. Should her theories be taken seriously?

By Andrew Lawler, Published December 10, 2021

One day in 2017, the archaeologist Eilat Mazar asked her colleague Haggai Misgav to stop by her office at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. ‘She closed the door, opened a locker, and said: “Read this!”’ Mazar handed him a tiny piece of rounded and flattened clay, broken on one side and no larger than his thumbnail; he saw that it had distinct markings on its surface.

Misgav, who specialises in ancient inscriptions, glanced at what he recognised were archaic Semitic letters. ‘It says “Isaiah” – a common name,’ he told her. Then Mazar handed him a magnifying glass. He peered more closely at other markings below the name. ‘It looks like the word “prophet”,’ he added.

‘That,’ said Mazar, ‘was why I called you in!’

She explained that the small oval of clay had been recovered in a 2,700-year-old garbage pit at the foot of Jerusalem’s acropolis – what Jews call the Temple Mount, and Muslims refer to as the Noble Sanctuary. The artefact was found less than a dozen feet from another clay lump that had been stamped with the personal seal of King Hezekiah. That Judean monarch is mentioned in the Bible as the 13th leader in a lineage that began with David.

According to scripture, Hezekiah and Isaiah not only lived at the same time – the 8th century BCE – but they had a stormy relationship. In one passage, when the ruler was deathly ill, the prophet told him it was a curse sent by God for his failure to marry. Hezekiah promptly recovered when he married Isaiah’s daughter.

Uncovering the men’s personal stamps, which are akin to modern signatures, in such close proximity would bring to life a pair of famous figures from the Hebrew Bible, what Christians call the Old Testament. If the seal she showed to Misgav did indeed read ‘Belonging to Isaiah the prophet’, as she believed, then Mazar had found the first physical evidence for one of Judaism’s most important prophets, as well as that of Hezekiah himself.

By this time, Mazar was already arguably the world’s most renowned biblical archaeologist. Her Jerusalem discoveries were legion. In 2005, she had uncovered what she argued was the palace of King David, and went on to pinpoint remains that she believed were the quarters of his successor and son, Solomon. She had also found evidence for the wall built by Nehemiah after the Judean elite returned from Babylonian captivity in the 6th century BCE. One particularly surprising discovery was that of a golden medallion featuring a menorah from the height of Christian Byzantium in the 7th century CE. And she had unearthed an array of other seal impressions linked to individuals also mentioned in the Bible.

On closer analysis, however, Misgav began to have grave doubts about his first reading. The word he had initially read as ‘prophet’ was broken off and missing a key letter. He became convinced that a far more likely reading was that of a personal name unrelated to the religious seer. He also noted that seals from that era were typically used only by businessmen or government officials. Misgav estimated there was less than a one-in-five chance that the impression in clay was made by a seal owned by the famous Isaiah.

He relayed his concerns to Mazar, who nonetheless published the article ‘Is This the Prophet Isaiah’s Signature?’ (2018). While she acknowledged the missing letter and admitted that it was ‘speculative’ to assign the seal impression to Isaiah the prophet, Mazar insisted that its proximity to the Hezekiah seal impression was important circumstantial evidence. She ended on an upbeat note, concluding that the find ‘leads us to consider the personality and the proximity of the prophet Isaiah as one of the closest advisors to King Hezekiah’.

That Bible-as-guidebook approach fell from favour among academics long ago

Predictably, her announcement drew extensive media coverage. Discovering a seal matching the name of figures mentioned in an old Egyptian or Mesopotamian text typically would cause a stir only in limited scholarly circles. But given there are 15 million Jews and 2.5 billion Christians, a find directly related to well-known characters in the Bible can immediately generate widespread international publicity.

While much of that reporting mentioned the academic parsing of ancient Semitic letters, the discovery was greeted by many as the latest example of archaeology confirming a passage in the Bible. One Israeli publication, for example, brushed aside the letter controversy by naming it the top biblical archaeology find of 2018, while an online exhibit by the evangelical Christian college in Oklahoma that supported Mazar’s dig proclaimed: ‘Seals of Isaiah and King Hezekiah Discovered’. Though technically correct – there was no question the seal was that of a man named Isaiah – this statement was at best misleading.

Mazar’s career was cut short when she died this May, aged 64, leaving a legacy of notable finds and an impressive publication record. Up until the end of her life, she remained one of the last university scientists digging with a spade in one hand and a Bible in the other, eager to uncover clues to the people and places described in scripture.

That Bible-as-guidebook approach fell from favour among academics long ago. Excavators today are generally less enamoured of unearthing royal tombs and ancient shrines than with determining what people ate, with whom they traded, and how their material culture changed over time. Yet the Hebrew holy book continues to exert a peculiar hold over Israeli archaeology. That pull is directly related to the furious political and religious struggle that roils a city held in esteem by billions of people of different faiths, and claimed as the capital of two distinct peoples. Mazar’s passing marks the end of a long era, but it is unlikely to alter that stark reality.

American Protestant clerics launched the field of biblical archaeology nearly two centuries ago, when holy writ was under attack from the revolutionary ideas generated by geology and biology. They seized on the new tools of excavation to combat growing scepticism about Christian ideas on the origins of Earth and humans. That singular mission morphed into a desire to pinpoint places mentioned in the Bible and to confirm the events and people familiar to its readers.

Starting in the 1830s, biblical explorers flocked to the Holy Land and Jerusalem with their compasses, shovels, and well-thumbed copies of the Good Book as their all-purpose guide.

In the early decades of Near Eastern archaeology, ancient texts such as the Bible played a critical role in forwarding research. Thanks to the Rosetta Stone, Egyptian hieroglyphics were deciphered in the 1820s, opening a door to a civilisation that until then was poorly understood. Later scholars cracked the code of the cuneiform writing of Mesopotamian empires such as Babylon and Assyria, providing a wealth of data on those societies.

Over time, however, archaeologists grasped that Near Eastern rulers, priests and scribes were apt to exaggerate and even make up historical events to suit their political and religious needs. Archaeologists confirmed, for example, that the mythical Sumerian figure of Gilgamesh was, in fact, king of the ancient Sumerian city of Uruk. But they did not have to take literally the well-known story of his discovery of the secret of immortality.

Ben-Gurion looked to the Bible much as Americans look to the Declaration of Independence

The Bible, of course, was no exception. Yet since it was taken literally by many Protestants, biblical archaeologists were slow to confront the contradictions and even fabrications that riddle the text. By the Second World War, academics had come to chafe at what they saw as strained efforts by devout Christian scholars to align their finds with the word of God.

Then came the creation of the state of Israel in 1948. The first generation of Israeli Jewish archaeologists fanned across the land, many of them searching for evidence of ancestors described in the Bible. Unlike their American and European predecessors, who often were Christian clergy, these excavators were typically Zionist and secular. They shared the view of Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, who looked to the Bible much as Americans look to the Declaration of Independence or the Constitution, as the very foundation of national life.

When Israel conquered East Jerusalem, including the Old City with its many religious sites, in the Six-Day War in 1967, the country’s archaeologists gained access to the heart of the Holy Land that had long been under Jordanian occupation. One of the largest subsequent digs took place just south of the Western Wall Plaza, in an area that was created when Israeli bulldozers demolished a medieval Arab quarter.

The man who led the excavation was hailed as the dean of Israel’s biblical archaeologists. Benjamin Mazar, grandfather to Eilat, was a Polish-born immigrant educated in prewar Germany who received Israel’s first dig permit. He went on to become president and rector of the premier institution of higher learning at the time, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Digging at the foot of the city’s acropolis, his team uncovered early Islamic palaces and Roman homes.

But public imagination was especially captured by what lay below. The excavation revealed monumental buildings from the Judean metropolis in the century before the Roman destruction of 70 CE. For many Israeli Jews, Benjamin Mazar’s discoveries provided physical evidence backing Israel’s claim to Jerusalem as its ‘eternal capital’.

The 10-year-old Eilat Mazar worked on her grandfather’s dig, and each weekend she served coffee to leading Israeli academics and politicians who gathered in her grandfather’s living room. The younger Mazar went on to study archaeology at Hebrew University, and spent much of her time researching a Phoenician cemetery in northern Israel. She returned to Jerusalem for good in 1981 to assist in a dig led by a former Israeli paratrooper-turned-archaeologist named Yigal Shiloh.

While the elder Mazar had uncovered the Judean Jerusalem under Herod the Great, Shiloh hoped to find the city captured by David and embellished by his son Solomon 1,000 years earlier. Archaeologists had long believed this City of David – the original core of the city – lay outside the walls of the Old City, on a rocky spur of land extending south from the city’s acropolis. Biblical accounts suggested that Jerusalem in that era was an impressive city that became the centre of a short-lived empire, but excavators had yet to find any sign of early Israelite occupation. After a half-dozen years of intensive excavations, Shiloh uncovered impressive ruins, but most appeared to date to previous eras in which Canaanites dominated or to later centuries.

This absence of evidence was more than a scientific puzzle. It was also a political embarrassment. Israel had incorporated the ridge, along with the rest of East Jerusalem, into the borders of its national capital. What Israeli Jews called the City of David was a crowded Palestinian village that Arabs called Wadi Hilweh. Right-wing Jewish groups sought to settle Jews on the ridge, and tensions between the two peoples sparked occasional violence. Lacking concrete proof of the glory days of David and Solomon, Israel’s claims to the ridge rang hollow.

He argued that David was little more than a tribal chieftain, and Jerusalem a scruffy mountaintop village

This gap in Jerusalem’s history gnawed at the younger Mazar. ‘This lack of evidence encouraged the argument that, in the time of David and Solomon, the city didn’t exist as the Bible said,’ she explained. She and her grandfather collaborated in 1986 on a small dig just to the north, near the southern wall of the Temple Mount, but failed to find material that could be attributed to David or Solomon’s reign. Then came word in 1993 that excavators in northern Israel had found an inscription mentioning ‘the house of David’. It was the first non-biblical reference to this king from ancient times. Soon after, researchers at the Louvre announced that a carved stone on display there contained a similar reference. These finds seemed to corroborate David’s existence, which some scholars had doubted.

Both Mazars were emboldened by the discoveries. After looking through old dig reports and examining biblical accounts, they agreed that David’s palace would likely be found at the northern end of the newly created City of David National Park, which lay on the northeastern shoulder of the rocky ridge. Their analysis hinged on a mention of David ‘going down’ to the city’s Canaanite fortress from that palace. His administrative centre, therefore, would be found just uphill from a fort that presumably was located on the slope above the town.