Workers are trying to protect key religious sites damaged in the recent earthquakes before the rains come.

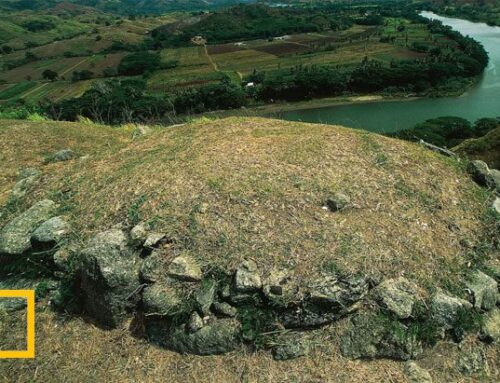

One of Nepal’s oldest and most venerated shrines, the Swayambunath temple complex suffered damage in the April 25th and May 12th earthquakes. Conservators hope to shore up the main stupa before monsoon rains arrive.PHOTOGRAPH BY NIRANJAN SHRESTHA, AP

High on a hill overlooking Kathmandu, the golden-spired Swayambhu shrine has drawn Hindu and Buddhist pilgrims for at least 1400 years. Now it is drawing conservators racing to fix ominous fissures in the main white-domed stupa as the summer monsoon fast approaches.

“There is fear of a landslide, and we have to take care of these cracks before the rainy season,” says Christian Manhart, the head of UNESCO’s mission in Nepal.

Nepalese and foreigners are working to pick up the pieces of the country’s heritage following the April 25 earthquake and a second tremor on May 12 that together killed more than 8,500 people, injured some 23,000, and left hundreds of thousands homeless. (Watch: Why Earthquakes Are Devastating Nepal.)

The quakes also wreaked havoc on Nepal’s ancient heritage that is central to the day-to-day lives of many Nepalese, and is a big draw for revenue-producing tourists. According to UNESCO documents, more than 30 monuments in the Kathmandu Valley collapsed in the quakes, and another 120 incurred partial damage.

Nepalese troops look for bodies at Patan Durbar Square. Looting at damaged and destroyed shrines and temples has been minimal, according to UNESCO officials. Bulldozers used to clear debris are a bigger threat.PHOTOGRAPH BY BRIAN SOKOL, PANOS

Manhart and Nepali colleagues estimate that it will take at least $160 million to repair and restore 1,000 damaged and destroyed monasteries, temples, historic houses, and shrines across the country. For this deeply religious nation, the reconstruction is a high priority, particularly in a time of despair and mourning. (Read about Nepalis interpreting the quakes as divine retribution.)

“In many places, devotees can’t access the temples because they are unsafe or simply destroyed,” says French archaeologist and art historian David Andolfatto, a UNESCO consultant in Kathmandu. “At Swayambhu, people used to go every morning to circumambulate the main stupa [a mound housing sacred relics]. Now it isn’t possible as the site isn’t safe.”

Trying to Stop the Bulldozing

Andolfatto was in his office when the second quake hit. He rushed to the street and jumped on his bike to check on Swayambhu, which lies just west of the city. He has spent most of his days there ever since.

Along with repairing the stupa cracks, he is supervising efforts to remove endangered mural paintings from a small nearby temple named Shantipur. This requires careful coordination with the local clergy, since only priests can enter the inner sanctuary.

VIRGINIA W. MASON, NG STAFFSOURCE: UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE CENTRE

In Kathmandu’s Durbar Square in the center of the capital, the Hanuman Dhoka Palace Museum is in a dire state, according to Manhart. “The walls and roof have disintegrated,” he says. “There are 6,000 objects and no storage space. Other museums have been destroyed.” (See 13 pictures from a father and son who are shooting quake-ravaged Kathmandu, their hometown.)

The army is guarding the site, and workers are now shoring up the walls and finding other parts of the palace to store objects before the rains arrive.

Fortunately, Manhart says, looting has been minor. Statues and carved lintels litter the sites of collapsed temples and shrines, but local communities are policing these areas. The biggest threat comes from bulldozers clearing debris that may contain ancient and fragile materials.

“The Ministry of Culture is trying to stop the bulldozing at places like Kathmandu’s Durbar Square, but the government is under pressure to find bodies that might be under the rubble,” Manhart says.

Ancient carvings at Patan Durbar Square are extracted from the rubble. Three other important squares in the Kathmandu Valley, part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site, were hard hit by the quakes, but most are well documented. That will make it possible for them to be rebuilt.PHOTOGRAPH BY BRIAN SOKOL, PANOS

Buildings Collapsed in a Heap

According to UNESCO’s damage assessment, which will soon be publicly released, the destruction from the quakes is concentrated in the Kathmandu Valley, which holds a special place in South Asian history. While Buddhism largely disappeared in India by the 12th century, it continued to flourish in Kathmandu. “We have this wonderful mixture of Hinduism and Buddhism,” says Andolfatto.

For example, the pagoda-style temple likely evolved there and spread across Asia, he adds. And these traditions remain vibrant—or did, until the earthquakes toppled dozens of structures.

“People go to the temples on a daily basis for their worship or spend some time in the Durbar Square, enjoying the architecture, a cup of tea, and the mountains in the background—when the pollution is not too bad,” says Andolfatto.

UNESCO designated seven groups of multi-ethnic monuments clustered in the valley as a single World Heritage Site, including Swayambhu, the Durbar squares of Kathmandu, Patan, and Bhaktapur, and the Hindu temples of Pashupati and Changu Narayan. Most of the temples were built with brick, timber, and mud mortar, with richly decorated windows and doorways and terracotta roofs often supporting golden cubes emblazoned with Buddha’s all-seeing eyes.

Especially hard hit in the quakes were the structures in the three Durbar squares, as well as Changu Narayan, according to Andolfatto. The 1655 temple in Sankhu in the northwestern end of the valley, famed as the site of caves where spiritual masters attained unusual powers, suffered extensive damage as well. Many of the ancient buildings simply collapsed in a heap.

Manhart says that UNESCO and the Ministry of Culture are focusing now on consolidating damaged monuments at risk of collapse during the coming rainy season that lasts through the summer. Then they will turn to restoring collapsed structures, including historic houses.

Fortunately, he says, there are extensive architectural drawings that provide a solid basis for reconstruction. Donations now top $400,000, he adds, and a total of $2 million is pledged from Sri Lanka, Germany, Austria, Japan, Korea, and other nations.

Drones provided by California-based Skycatch is providing engineers, planners, and donors with a clear view of the earthquake damage.PHOTOGRAPH BY CASEY STOKELY, SKYCATCH

Mapping Damage With Drones

Meanwhile, the California-based company Skycatch is flying drones above cultural heritage sites to provide engineers, planners, and donors with a clear view of the damage. The company’s CEO, Christian Sanz, sent a team with two drones to Kathmandu days after the first quake, and later donated a total of five drones, computers, and training sessions to UNESCO and the Ministry of Culture’s Department of Archaeology.

These vehicles, which are two-feet in diameter, cost about $10,000 to $15,000 and produce high-resolution 3D images. Sanz, who just returned from Kathmandu, says that so far the drones have shot 50,000 images over 50 flights, producing 50 maps that are now being used to analyze the extent of damage across the valley.

While the death toll and destruction from the tremors is horrific, it is not new. A tremor in 1255 killed up to one third of the valley’s population, and the Machhendra Nath temple at Patan collapsed during a quake in 1408. Other seismic events are recorded in 1681, 1810, and 1833.

A century later, in 1934, the most devastating tremor yet recorded in Nepal—8.0 on the Richter scale–killed double the number who died in the most recent quakes.

Andolfatto is confident that the Nepalese people will overcome the tragedy and recover a cultural heritage that is as much about private worship, group rituals, and communal festivals as it is about venerated buildings. “We’ve lost the spirit of many places,” he says. “But it will come back.”