Firsthand accounts reveal worse damage than expected in war-torn regions

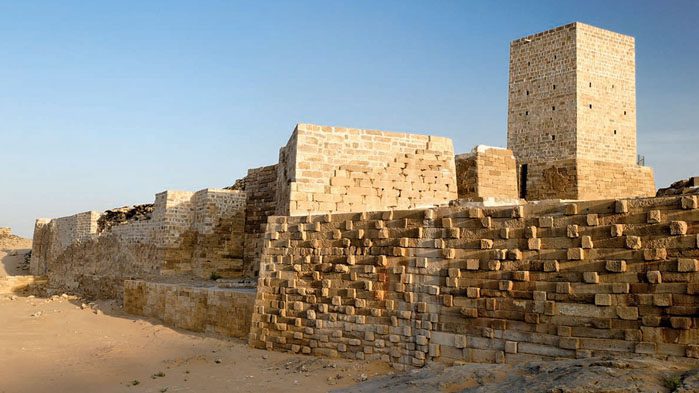

Some Yemenis suggest that the 2800-year-old Marib Dam, one of the country’s best known ancient sites (shown

before it was bombed), was deliberately targeted.

A new front has opened in the destruction of archaeological heritage in the Middle East. Across northern Iraq and Syria, the Islamic State (IS) group devastated antiquities during its reign of terror starting in 2014, pulverizing classical statues such as those of Palmyra in Syria and bulldozing a 3000-year-old ziggurat at Iraq’s Nimrud. The IS group has now been routed by Iraqi and Syrian forces, curbing the destruction but giving archaeologists a firsthand look at an aftermath that is grimmer than many had expected. Meanwhile, the assault on antiquity has extended to Yemen, 2000 kilometers to the south, another archaeological treasure house riven by conflict.

“Our immortal history has been wasted by wars,” lamented Mohanad Ahmad al-Sayani, chair of Yemen’s General Organization of Antiquities and Museums in Sana’a.

In Yemen, the cultural losses have gone largely unnoticed by the wider world but are keenly felt by archaeologists. Although the country has been far less studied than Mesopotamia, it played a critical role in the rise of empires and economies in the region starting around 1000 B.C.E., researchers said at a meeting here last week of the International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East.

By 1200 B.C.E., the kingdom of Saba in what is now central Yemen controlled the export of frankincense, derived from a tree that grew only along the country’s southern coast. The prized resin was burned for a millennium and a half in temples from Persia to Rome. The vast wealth of Saba—home to the biblical Queen of Sheba—funded impressive temples, cities, and engineering marvels.

Among them was the Marib Dam, built on Wadi Adhanah in the eighth century B.C.E. to help expand agriculture in this arid region; some claim it is the world’s oldest dam.

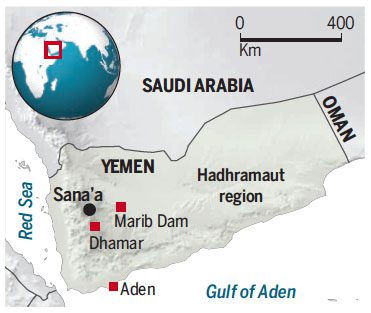

Today, Yemen is racked by civil war and Islamic extremists who, in a campaign against heresy, have destroyed ancient mosques in the port city of Aden, and a multidomed shrine in the Hadhramaut region (see map, right).

Bombs dropped by the Saudi-led coalition have wreaked the most damage, Al-Sayani said. The Marib Dam, in an unpopulated area far from the capital, was struck in 2015, leaving a deep gash in the well-preserved northern sluice gate. The regional museum of Dhamar in the southwest, which contained thousands of artifacts from the Himyarite Kingdom, was completely destroyed. The Himyarites conquered Saba in 280 C.E., took over the frankincense monopoly, and became key players in the expanding Indian Ocean trade between the Roman Empire and India until Ethiopian forces overthrew them in 525 C.E.

Al-Sayani showed images from a dozen flattened or severely damaged sites, including medieval castles such Aden’s Sira Fortress, and the centuries-old al-Qassimi neighborhood in Sana’a. More than 60 sites have been destroyed or severely damaged since the conflict began in 2015, Al-Sayani said, chiefly from Saudi bombings. Although some were strategic targets, he charged that the Saudi attacks were a conscious campaign to wreck Yemen’s heritage and demoralize its citizens. “After 3 years of assessing the damage, I believe the bombing is being done with a purpose, since many of these sites are not suitable or useful for military use,” he says.

The destruction seems deliberate, agrees archaeologist Sarah Japp of Berlin’s German Archaeological Institute. “The Saudis were given information on important cultural heritage sites, including exact coordinates,” by UNESCO, said Japp, who was based in Sana’a before the war. UNESCO intended to protect the sites, but she fears that the data may instead have been used for targeting. “There is no reason to say all of these [bombings] are just accidents.” The Saudi embassy in Berlin and officials in Riyadh did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Meanwhile, 2000 kilometers to the north in Syria and Iraq, the damage wrought by years of IS group control is only now coming into focus. “It is nothing short of a catastrophe,” said Michel al-Maqdissi, former head of excavations in Syria’s antiquities department in Damascus, who now works at the Louvre in Paris and maintains contacts in Syria. Some of the worst reports come from Mari, a 60-hectare site on the banks of the Euphrates River that 4000 years ago was one of the world’s largest cities. Just north of Sumer and the Akkadian Empire, Mari served as a key trading center for Mesopotamian goods and Anatolian metals and stone, and once boasted the best preserved early palace in the Middle East.

But no longer. Archaeologist PascalButterlin of Pantheon-Sorbonne University in Paris, who worked at Mari for years and has gathered information from Syrian sources, displayed an image of the palace from the ground that shows near total destruction of Mari’s central area. The site’s ancient statues were removed to museums long ago, so the reasons behind the destruction remain murky, although the IS group’s desire to profit from antiquities is well-known. A nearby large moundcalled Tell Medkouk was bulldozed completely to unearth objects for looting. From satellite data on the center of Mari, Butterlin estimates that looters dug some 1500 pits, many of them more than 5 meters deep and 6 meters wide. The vehicle tracks “make it look like they had traffic jams there,” he said. He suspects that thousands of looted cuneiform tablets, small figurines, and bronze objects won’t show up on the art market for years, as sellers wait for international outrage to cool.

But no longer. Archaeologist PascalButterlin of Pantheon-Sorbonne University in Paris, who worked at Mari for years and has gathered information from Syrian sources, displayed an image of the palace from the ground that shows near total destruction of Mari’s central area. The site’s ancient statues were removed to museums long ago, so the reasons behind the destruction remain murky, although the IS group’s desire to profit from antiquities is well-known. A nearby large moundcalled Tell Medkouk was bulldozed completely to unearth objects for looting. From satellite data on the center of Mari, Butterlin estimates that looters dug some 1500 pits, many of them more than 5 meters deep and 6 meters wide. The vehicle tracks “make it look like they had traffic jams there,” he said. He suspects that thousands of looted cuneiform tablets, small figurines, and bronze objects won’t show up on the art market for years, as sellers wait for international outrage to cool.

The situation is even worse at Dura-Europos, which until recently was a remarkably well-preserved city upstream of Mari. From the first century B.C.E., this city lay on the frontier of the Roman and Persian empires, which took turns controlling it, and once held both one of the world’s oldest Jewish synagogues and oldest Christian churches. “The scale of the disaster there is profound,” said Chekmous Ali, a Syrian archaeologist now at the University of Strasbourg in France. “There are innumerable pits—some 9500—and the necropolis is gone.” Across the border in Iraq, the old city of Mosul once boasted a host of Islamic and Christian monuments, many destroyed or damaged during the IS group’s 3 years of control. But the worst devastation came last summer, when more than 30,000 bombs and missiles hit historic buildings during the battle for the city, said Karel Novácˇek of Palacký University Olomouc in the Czech Republic. “The old city was annihilated,” he said at the meeting. He charges that the destruction continues, as Iraqi construction crews clear the wreckage without trying to preserve what’s left or tally the damage.

“The heritage management is nonexistent,” he said. “We need careful removal of the rubble, but that is not happening.” His team is assembling what data they can from old reports and photographs that could provide

some basis for reconstructing historic sites. He plans to lead an on-the-ground assessment in June, in hopes of providing Iraqis a chance to mend what they can of their battered cultural heritage.