The very first English colonists brought with them people of varied ethnicities, and the historical record is clear that they also promptly intermarried with Native Americans.

When white nationalists clashed with their opponents in the streets ofCharlottesville last August, the violence marked the latest battle in an old war. For many anxious and angry whites, our roots as an English-speaking Protestant nation under British laws are under attack. U.S. Attorney GeneralJeff Sessions alluded to this in February, when he praised the country’s “Anglo-American heritage.”

But recent historical and archaeological finds don’t square with the traditional view of doughty colonists “taming a continent,” as President Donald Trump put it in his May speech to Naval Academy graduates. Foreigners, it turns out, were essential to English success in the New World, as were the indigenous groups they encountered. And long before Ellis Island, at the very start of the American experiment, whites flouted English law by mixing their genes as well as their culture with peoples from three continents.

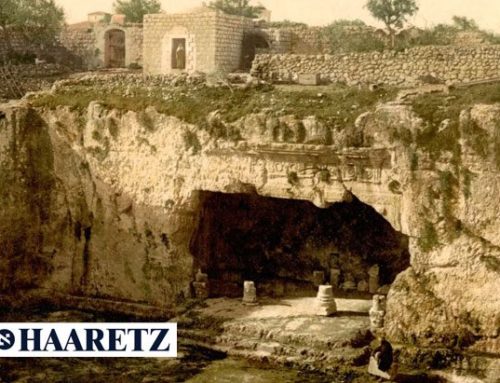

When Sir Walter Raleigh launched England’s first attempt to settle the Americas in 1585, his country was a poor and backward place on Europe’s fringe. The knight had to hire a Portuguese pirate to transport the colonists to Roanoke Island on the coast of North Carolina, and a German Jew to identify precious metals once they arrived—a radical move for a country that had banned Jews for three centuries. Two decades later, at Jamestown Island in Virginia, one London backer noted “we have already provided and sent thither skillful workmen from foreign parts.”

Once the English arrived on Roanoke and Jamestown and, still later, at Plymouth in Massachusetts, they depended heavily on the local Algonquian-speaking peoples for food supplies traded to the ill-prepared immigrants. Excavations also show that the two peoples did not live as rigorously separate as once thought. At Jamestown, for example, vast numbers of Indian artifacts found recently in the early fort, from mussel shell beads and stone tools to earthen pots, show that indigenous people were living and working among the English.

They inevitably shared genes, as well as goods and technology, despite harsh punishments designed to prevent this. Spanish spies at Jamestown reported that forty or fifty English abandoned their countrymen to live with Indian wives. In 1612, the Virginia governor had the deserters captured and then “hanged, sunburned, some broken up on wheels, others to be staked and some shot to death” to discourage others from following suit.

Pocahontas’ marriage to John Rolfe two years later proved the exception to the rule. In 1691, Virginia forbade settlers from marrying the indigenous people, as well as the Africans brought in to work the expanding tobacco plantations, “for prevention of that abominable mixture and spurious issue.” Similar laws remained on Virginia’s books until 1967.

Yet Colonial America’s dirty little secret, exposed by historians in the past decade or two, was that most of the settlers who were captured by or who willingly fled to Native American societies usually refused to return. In 1747, New York’s surveyor general reported with dismay to the king’s council that “no arguments, entreaties, no tears of their friends and relations, could persuade many of them to leave their new Indian friends.” The few who did “run away again to the Indians and ended their days with them.”

Benjamin Franklin remarked with only some exaggeration that “no European who has tasted savage life can afterwards bear to live in our societies.” This wasn’t a case of Stockholm syndrome, in which hostages develop a close bond with their captors—it didn’t work both ways. “We have no examples of even one of these Aborigines having from choice become Europeans,” wrote one New Yorker in 1782.

For English settlers, who firmly believed that they brought the tools of civilization and the light of Christianity to their barbaric neighbors, these desertions were deeply troubling. Nowhere is that more evident than with Raleigh’s second attempt to establish an English settlement on Roanoke Island. In 1587, 115 English men, women, and children landed on Roanoke. War with Spain severed their contact with England, and when a rescue mission arrived three years later, the settlers had vanished.

Elizabethans quite sensibly assumed that the abandoned colonists mixed with the locals. “They have married with the Indians, and make ’em bring forth as beautiful faces as any we have in England,” wrote Ben Jonson in a 1605 smash-hit comedy on the London stage. But later Americans largely ignored what was seen as an embarrassing failure until the 1830s, when a Harvard historian re-envisioned the effort as a romantic mystery.

Everything from aliens to zombies have since been evoked to explain the disappearance of the Lost Colonists.

Yet most historians, anthropologists, and archaeologists today agree with the Elizabethans—that at least some of the settlers became Indians rather than starve. When the second wave of English arrived in the 17th century, those Native Americans who had survived European diseases retreated into remote Carolina swamps, where they were, in time, joined by renegade whites and escaped African slaves. These mixed communities were deemed colored. The colonists’ likeliest descendants, therefore, would today be considered African American.

“America was founded by white people,” says David Duke. “It was founded for white people. America was not founded to be a multiracial, multicultural society.” It’s an old belief, but one that is factually incorrect.

There is no denying the American debt to British representative democracy and common law, not to mention our language. And it is true that the bulk of our citizens trace most of their ancestry back to Europe. But thanks to excavations in trenches and among archives, we know that the United States was, from its very beginning, a multiracial and multicultural society, and it never ceased being so.

Of course, myths can’t be conquered by facts, and beliefs are not subject to scientific proof. But if we want to prevent the sort of violence that wracked a quiet Virginia college town one year ago, we will have to move beyond the corrosive concept of a nation founded by only one sort of people. We will have to embrace an America that is, as Vice President Hubert Humphrey said, is “all the richer for the many different and distinctive strands of which it is woven.”