New research suggests that one of the state’s greatest historians had a hand in perpetrating an infamous hoax.

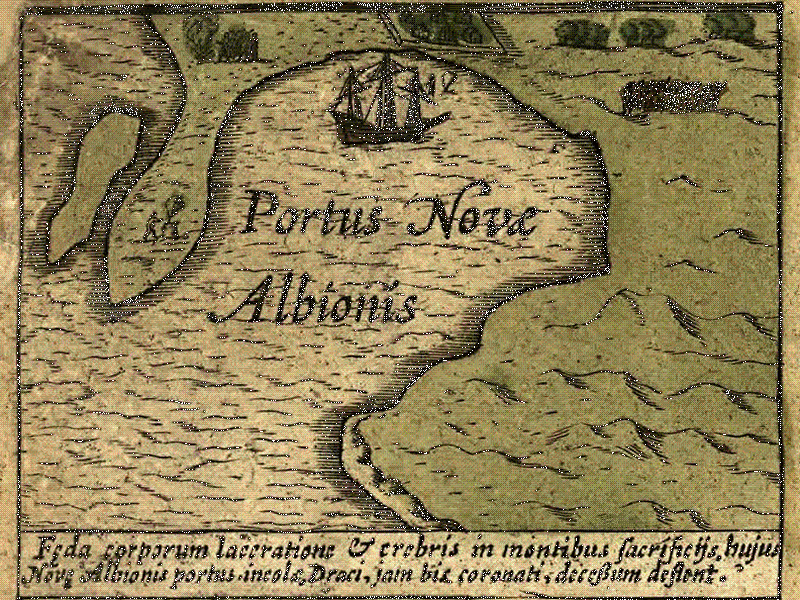

The Hondius map of 1589 inset depicts Drake’s encampment at New Albion, Portus Novas Albionis. (Wikicommons)

Few sea voyages are as famous as that of the Golden Hind, privateer Francis Drake’s around-the-world voyage that ended with his arrival into England’s Plymouth harbor in 1580. Along with being a remarkable feat of seamanship, the world’s second circumnavigation, among other achievements, was the first to map large portions of North America’s western coast. Filling the Hind’s hold as it berthed in Plymouth were a half-ton of gold, more than two-dozen tons of silver, and thousands of coins and pieces of jewelry looted from Spanish ports and ships along the western shore of South and Central America. Drake’s lucrative journey helped spark England’s ambitions for global empire.

After their Spanish raids, as described in written reports by Drake and other crew members, the Golden Hind landed along the west coast of North America for several weeks to caulk his leaky ship and claim the land for Elizabeth I, the first formal claim by an Englishman to a piece of the Americas. To commemorate that act, Drake posted a “a Plate of Brasse” as a “monument of our being there,” according to an account by one of the crew.

But just where Drake, about 80 crewmen, and one pregnant African woman named Maria stepped ashore has been a matter of acrimonious dispute for nearly a century-and-a-half. Most of the expedition’s details were immediately classified by the queen, who worried that the news of Drake’s claim would instigate open war with Spain. What was published in subsequent decades was often incomplete and ambiguous. As a result, professional and amateur scholars poring over contemporary maps, letters and other documents have proposed candidate harbors from Mexico to Alaska.

In 1875, an English-born geographer named George Davidson, tasked with conducting a federal survey of the U.S. West Coast, pinpointed a bay about 30 miles northwest of San Francisco, a site that seemed to match the geography and latitude described by Drake and his crew. He had the bay renamed in honor of the privateer. Influential Californians quickly embraced the treasure-hungry captain as the natural native son of a state that prided itself on the Gold Rush. Drake also gave the state an English “founder” who arrived long before the settlement of Jamestown and Plymouth, an alternate origin story that could replace those of Spanish missionaries and indigenous populations.

Californians in the early 20th century celebrated the man knighted for his piratical exploits with memorials, parades and pageants. His name was bestowed upon a boulevard in Marin County and San Francisco’s premier hotel at Union Square. In 1916, the California legislature passed a resolution commemorating the man who “landed on our shores and raised the English flag at Drakes Bay.”

In 1937, a leading historian at the University of California, Berkeley, Herbert Bolton, announced the discovery of Drake’s “Plate of Brasse” at a site not far from Drakes Bay. The sensational find, etched with words claiming Nova Albion—New England—for Elizabeth, included Drake’s name. Dated June 17, 1579, the plate reads in part, “BY THE GRACE OF GOD AND IN THE NAME OF HERR MAIESTY QVEEN ELIZABETH OF ENGLAND AND HERR SVCCESSORS FOREVER, I TAKE POSSESSION OF THIS KINGDOME ….”

The discovery made headlines across the country, and turned Bolton into a national figure. The Berkeley professor, however, authenticated the rectangular plate and heralded it as physical proof of Drake’s landing north of San Francisco before conducting detailed historical and metallurgical tests. Though some historians expressed doubts about the plate’s legitimacy at the time, the university raised $3,500 to buy it, and the piece of tarnished metal became a cherished artifact still displayed at Berkeley’s Bancroft Library. For California’s elites, “the plate was not just a metal document or a valuable antique. It was the holy grail—a venerable Anglo-American, Protestant, religious relic,” writes Bolton’s biographer, Albert Hurtado.

Four decades later, however, researchers from Lawrence Berkeley National Lab subjected the plate to rigorous testing and concluded that California’s most famous artifact was made using modern material and techniques. It was, without question, a forgery, as many historians had long suspected. But other evidence, including the 1940s discovery of a cache of 16th-century Chinese pottery—thought by some archaeologists to have been purloined by the Hind—still pointed to Drake’s presence in northern California.

In a new scholarly book, Thunder Go North, to be published next week, Melissa Darby, an archaeologist from Portland State University, argues that Drake likely never made it to California at all—and that he wasn’t simply a privateer. Instead, she points to official English documents that show he was on a secret government mission of exploration and trade. She also cites Drake’s own writings that say that after raiding the Spanish to the south, he went far out to sea before heading back to the coast. Darby analyzes wind currents in that time of year—late spring—and contends that this would have put the Hind far to the north, likely in present-day Oregon.

She also highlights an overlooked contemporary document in the British Library that says Drake was seeking the Northwest Passage as a way to return to England—that would naturally have led to a more northerly course—and mentions a latitude consistent with central Oregon. As for the Chinese porcelain, she notes that a 2011 study concluded it all came from a 1595 Spanish shipwreck. In addition, Darby contends that anthropological evidence, such as plank houses and certain indigenous vocabulary, points to Drake meeting Native Americans living in the Northwest rather than on the California coast.

“Because the vexed question [of where Drake landed] has largely been in the domain of rancorous proponents of one bay or the other, the question has become a quagmire that professional historians and archaeologists have largely avoided,” writes Darby of her book. “This study is a necessary reckoning.”

Her most explosive assertion, however, implicates Bolton, one of California’s most distinguished historians and a man heralded as a pioneer in the study of colonial Spanish America, in the hoax of Drake’s brass plate, one of the country’s most infamous cases of forgery.

“He was a flim-flam man,” Darby tells Smithsonian magazine. “It is almost certain that Bolton himself initiated the ‘Plate of Brasse’ hoax.”

Though the laboratory analysis revealed the plate as fake in 1977, who was behind the deception and their motive remained a mystery until 2003, when a team of archeologists and amateur historians published a paper in the journal California History concluding that the plate was a private prank gone awry. They told reporters that the episode “was an elaborate joke that got terribly out of hand.”

A highly respected academic, Bolton also served as Grand Royal Historian of the Clampers, a men’s satirical club that sought to keep the ribald pioneer life of California alive and was “dedicated to protecting lonely widows and orphans but especially the widows.” The team failed to find a smoking gun but drew on published material and personal recollections. They concluded that the object was fabricated by a group of prominent San Franciscans, including one Clamper, and was “found” north of San Francisco as a prank to amuse Bolton, who had previously asked the public to keep an eye out for what Drake had left behind. By the time the news went viral, the prank had spun out of control and the hoaxers remained silent. Bolton, according to the researchers, was the butt of the joke.

But in her book, Darby contends that Bolton was far more likely to be a perpetrator rather than a victim of the hoax. She tracks how Bolton and other prominent California men sought for decades to ignore and discredit scholars who opposed the story of Drake as a rogue pirate landing on the shores of Drakes Bay. For example, he blocked Zelia Nutall, a respected anthropologist, from publishing a paper suggesting Drake landed north of California. Darby also describes a pattern of deception going back to his early years as an academic.

“A thief does not begin his career with a bank heist,” she writes. “The plate was not Bolton’s first attempt at pulling the wool over the eyes of the public.”

Darby details how Bolton was often associated with a host of scams and schemes relating to Spanish or pirate treasure. In 1920, he publicly authenticated a 16th-century Spanish map pointing to a rich cache of silver and gold in New Mexico that set off a media frenzy. It proved a fake, but gave Bolton his first taste of national renown.

The next year Bolton claimed to have translated an old document that gave clues to an ancient trove of nearly 9,000 gold bars hidden near Monterrey, Mexico. When he declined a spot in the expedition organized to find it and a share in the profits, he again made headlines by turning down the offer because of his pressing academic duties (“18 Million Spurned by U.C. Teacher” read one; another said “Bolton Loses Share in Buried Treasure”). No treasure ever surfaced.

In other instances of old documents and lost treasure, he brushed off accusations of fudging the truth.

“This was Bolton’s method,” writes Darby. “Create a good story for the gullible public, and if it was exposed, call it a joke.” In participating in the Drake plate hoax, she adds, he could reap not just media attention but draw new students to his program, which suffered during the depths of the Depression.

She suspects another motive as well. “The plate enabled Bolton to trump up the find and turn his sights to the largely white and Protestant California elites, who embraced Drake,” says Darby, because it “served to promote an English hero and stressed a white national identity of America.” Leading Californians of the day included members of men’s clubs like the Native Sons of the Golden West, which fought for legislation to halt most Asian immigration and to restrict land rights to many of those already in the state. “Bolton orated in front of the Native Sons, and they provided scholarships for his students,” Darby adds.

Bolton’s biographer, Hurtado, an emeritus historian with the University of Oklahoma, acknowledges that Bolton was “careless” in giving his stamp of approval to the plate without conducting adequate analysis. “There’s no question he was a publicity hound,” he adds. But he is skeptical that Bolton would actively risk scandal in the sunset of his career, when he was nearly 70 and highly esteemed. “He had no need to create a fraud to gain an international reputation. This risked his reputation.”

Members of the Drake Navigators Guild, a nonprofit group championing the Drakes Bay theory, soundly reject Darby’s assertion about Bolton. “The idea of a conspiracy doesn’t work,” says Michael Von der Porten, a financial planner and second-generation member of the guild whose father was part of the 2003 team that studied the hoax. He also dismisses her conclusions about a landing north of Drakes Bay. “This is yet another fringe theory, a total farce.”

Michael Moratto, an archaeologist who has been digging around Drakes Bay for decades, agrees. “I’ve spent 50 years listening to all sides of the debate, and for me it is settled.” Darby favors an Oregon landing site for parochial reasons, he adds, and “is twisting all of this to suit her own purposes.” He still maintains that some of the Chinese porcelain found at the bay came from Drake’s cargo.

Others find Darby’s arguments persuasive. “[Darby] did a superb job of mustering evidence and deciphering it,” says R. Lee Lyman, an anthropologist at the University of Missouri in Columbia. “And it is highly likely Bolton was perpetuating a subterfuge.” Nevertheless, he says that it will be an uphill struggle to alter the prevailing narrative, given the deep emotional resonance that Drake continues to have for many in the Golden State.

Darby says she expects pushback, particularly from the guild, which she characterizes as “an advocacy organization not an academic organization.” She adds that her conclusions about Bolton “will be a deep shock, and their denial is understandable.” But Darby is also confident that they will be swayed by careful study of her evidence. Lyman is not so sure. “The historical inertia placing Drake in California is so great,” says Lyman. “You get wedded to an idea, and it is hard to question it.”