They were looking for the past. They created the present.

By Andrew Lawler, Published January 27, 2022

The tome was perhaps not an obvious bestseller, but people snatched it up on both sides of the Atlantic. For some, it wasn’t just interesting; it was divinely inspired.

“They were obeying an impulse from on High,” one British reviewer wrote. “Jehovah meant them to be witnesses of His truth.”

Whether or not their trip was divinely guided, this novel marriage of science with religion proved irresistible to millions of Christian believers. It also put Jerusalem back on the physical map for Westerners at a moment when steamships and trains made it more accessible. Robinson and Smith had laid the basis for “an entire new scholarly, religious, and political enterprise in the Holy Land,” notes historian Neil Asher Silberman.

It was an enterprise that would reshape the Middle East.

One of those inspired by Robinson was a Disciples of Christ missionary from Virginia named James Turner Barclay. After settling in Jerusalem in 1851, he heard “marvelous tales about its subterranean passages, galleries, and halls.” An Ottoman official assured Barclay that beneath the city were “the magnificent subterranean remains of the gorgeous palaces of King David, Solomon, and various other monarchs of former times.”

Barclay didn’t find many Jews interested in converting to Christianity, so he spent his time surreptitiously exploring various caves and wrote a popular book about his adventures.

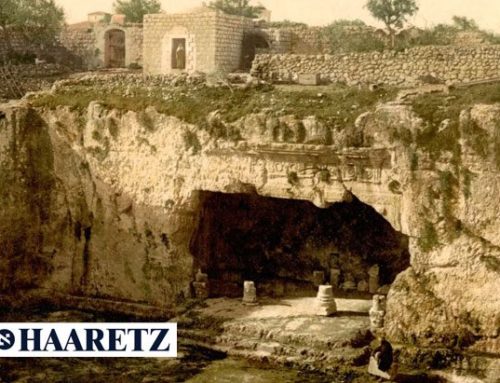

A dozen years later, in 1863, the Ottoman sultan in Istanbul issued the first license to excavate in Jerusalem. It went to a French senator named Louis Félicien de Saulcy.

A devout Catholic and confidante to French Emperor Napoleon III, de Saulcy quickly discovered an ancient sarcophagus in the Tombs of the Kings, the city’s largest tomb complex, located just north of the walled Old City. Despite complaints from Jerusalem’s Jews, who accused him of robbing their ancestors’ graves, the Frenchman declared he had discovered the bones of an ancient Judean queen. He had them shipped to the Louvre. His claim later proved false, but the exhibition of the world’s first purported biblical artifact proved a public sensation.

Not to be outdone by their French Catholic rivals, British Protestants quickly organized the Palestine Exploration Fund to bring back biblical remains for the British Museum. Their star explorer was an Anglican military officer named Charles Warren, who was also a dedicated Freemason fascinated by Solomon’s temple.

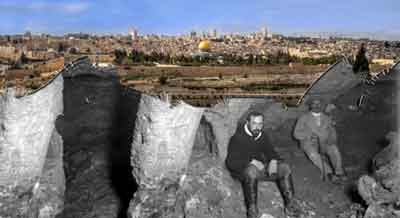

Scholars presumed that temple—said to have been destroyed by the Babylonians in 586 BCE—had once stood on the city’s acropolis. Muslims call this vast rectangle held up by massive stone walls the Noble Sanctuary, while Jews know it as the Temple Mount. Digging in what has long been Islam’s third-holiest site was strictly forbidden, so Warren tunneled his way around the enormous walled enclosure, sometimes using dynamite to remove underground obstacles.

This did little to endear him to Arab Muslims, who suspected the Englishman, quite plausibly, of attempting to undermine their holy site.

Soon enough, the residents of Jerusalem saw an unexpected side effect of all this excavation: tourists. Bevies of visitors—mostly American Protestants—started flocking to the city.

Like Robinson, early Western visitors often found themselves disappointed by the Holy City. Most Jews spoke Arabic, and Muslim imams jostled past Christian priests in the narrow alleys. The place seemed at odds with the Jerusalem they had learned about in Sunday school. One contemporary guidebook warned that little was left of the “far-famed capital of the Jewish Empire.”

Image: Illustration by CT / Source Images: WikiMedia Commons / Unsplash

Underground tunnels in Jerusalem.

The Westerners were happier underground. Warren’s tunnels, exposing passages and rooms from the days of Herod the Great, became major attractions, satisfying tourists’ appetite for what Jerusalem was “supposed to” look like.

Soon, German and Russian archaeologists joined the British and French in probing for evidence of the ancient Judean past. These explorers sought more than proof of Jerusalem’s biblical role. They also wanted to unearth remains that were valuable materially as well as spiritually. In 1909, a British aristocrat named Montagu Brownlow Parker even assembled a team of European psychics, code breakers, and engineers to seek out the temple treasures—including the ark of the covenant—rumored to lie beneath the city.

Parker estimated the artifacts were worth $5.7 billion in today’s currency. He and his peculiar excavation team tunneled for two years but failed to find anything beyond a few potsherds. Desperate to pay off investors, he used bribes to obtain access to the Dome of the Rock on the Noble Sanctuary. Discovered hacking away at the sacred stone beneath the dome, the team fled for their lives. It was rumored—falsely—they had made off with Solomon’s riches. The incident soured Arab Muslims on both Western explorers and the city’s Ottoman rulers. The scandal that ensued nearly brought down the Ottoman government in Istanbul.

European Jews were no more pleased with the ongoing excavation efforts than the local Muslims. From their perspective, Christians were attempting to abscond with important remnants of their heritage.

“We, who should be the most interested party in these archaeological excavations, do almost nothing in this field and leave to whomever else wants it: Germans, Americans, British,” one writer complained in a 1912 Russian-Jewish newspaper article.

Edmond de Rothschild, a French-Jewish banker, launched his own expedition to find the ark of the covenant in 1913. It was the first Jewish-led effort in the Holy Land. Rothschild, who also was working to settle displaced European Jews in Palestine, was eager to beat out Christians in the hunt for ancient Jewish treasures.

“Excavations be d___,” he told a friend. “It’s possession that counts.”

That dig ended without success when World War I broke out the following year. Yet the attention lavished on subterranean Jerusalem by the early Western explorers—and the tremendous press coverage accompanying each find—nourished a growing interest in the city among those Jews seeking an independent homeland for their people.

By the time the British conquered the city in 1917 from the Ottomans, Western Jews saw Jerusalem’s ancient sites as more than simply places of prayer. They became symbols of a Jewish nation. And what had begun as a Christian effort to prove the veracity of biblical history led to the beginnings of the state of Israel.

In the wake of World War II, the British relinquished the territory to the United Nations, and the nation of Israel was born. By then, in the aftermath of the Holocaust, many Jews felt a deep yearning to make Jerusalem their capital.

After 1967, when Israel captured the Old City from Arab forces, excavations continued but under the auspices of the Israeli government. These have focused on the Judean past, and Israeli politicians have often cited archaeology to claim all of Jerusalem as Israeli territory. This has drawn complaints, prompted protests, and sparked riots by Palestinians who see the Holy City as their own.

The search for biblical Jerusalem begun by Robinson continues to stir political and religious controversy. In fact, it is this very search that has made Jerusalem the contested city that it is today.