The metallurgist came to the Roanoke settlement looking for raw materials to support the English war effort.

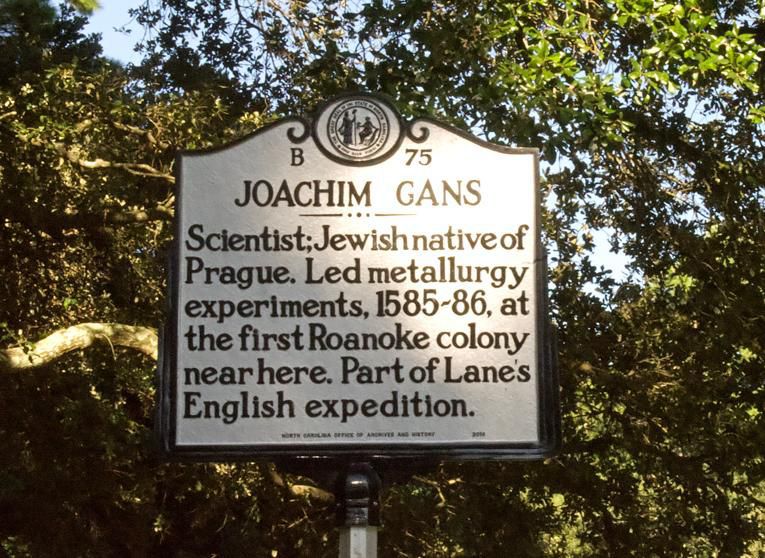

This marker now resides beside Highway 64 near the site of where the Roanoke settlement is believed to have sat. (Courtesy of Brindley Beach vacations)

Late last month, in a ceremony alongside a North Carolina highway, a small group of scholars and politicians unveiled a black-and-gray plaque dedicated to Joachim Gans, the first recorded practicing Jew in North America. A metallurgist from Prague, Gans played a key role in the first attempt by the English to settle the New World. His accomplishments in the 1580s helped plant the seed for what became the United States.

Gans’ long-delayed recognition comes at a time of escalating anti-Semitic attacks such as the deadly shootings targeting Jews earlier this year in Pittsburgh and near San Diego. The modest sign commemorating Gans is a potent reminder of the largely forgotten but surprising diversity that marked early English colonization.

It also arrives amid a national debate about the meaning of monuments and memorials to the Confederacy. The Gans marker now stands 200 miles east of the University of North Carolina campus where Silent Sam, a bronze statue of a Confederate statue, once stood. Erected in 1913, student activists toppled the statue last year and the controversy over whether or not to raise him back up continues to roil the state. Amid these controversies, highway markers like the one dedicated to Gans offer a quiet, cheap, and democratic alternative to memorialize new heroes ignored by previous generations.

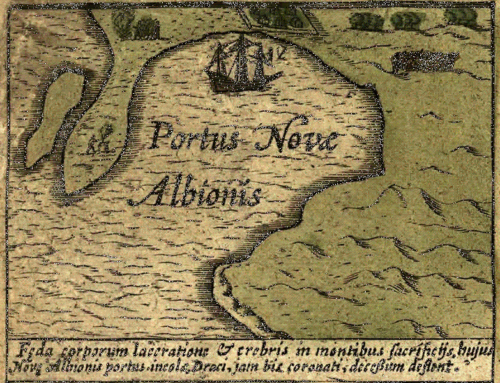

How did a German-speaking Jew end up in the first English colony in the Americas? Gans grew up in 16th-century Prague, then the center of innovation in mining and metallurgy. England was still a relatively poor and backward European country, desperate for help in extracting copper and tin. Growing tensions with the Spanish Empire would soon would lead to war, and the English needed cannon to arm their merchant ships and navy. Jews had been banned since 1290, but a courtier of Elizabeth I secured Gans a kind of Tudor H-1B visa. Soon after, Sir Walter Raleigh sought a credible scientist to join England’s first venture to colonize the Americas on what is now the North Carolina coast. In Gans, Raleigh saw the perfect candidate for the specialized job of sourcing and analyzing metals.

Gans arrived on Roanoke Island in 1585, along with a motley crew of more than 100 men that included French, Portuguese, Belgian, Irish and Scottish men as well as English soldiers and merchants. The Prague Jew, who made no secret of his religious background, quickly constructed a state-of-the-art chemistry lab outfitted with Bavarian crucibles and a high-temperature furnace. He tested metals brought to him by local Algonquian-speaking tribes and tramped through the swamps in search of mineral deposits. Though he failed to find gold, , as Raleigh had hoped, there is evidence he isolated iron, silver, and copper in his experiments. That was promising news for an England eager to access metal deposits.

Hunger and conflict with the indigenous population drove the settlers, including Gans, to catch a ride home aboard a passing fleet the following year. A second attempt to establish a beachhead at Roanoke in 1587 ended abruptly when the English war with Spain severed ties with the settlers. The fate of the 115 men, women, children, along with two infants born on the island, remains colonial America’s oldest mystery.

Raleigh’s venture failed, and memory of Gans’ contribution likewise vanished—as did he. The last known mention of the metallurgist has him facing trial in London for denying Christ was the son of God. Jews would not be officially allowed in England for another generation.

In the 1990s, archaeologists studying the former Roanoke settlement stumbled on the remains of his equipment and workshop; the material is the only undisputed physical evidence we have of the Roanoke settlement. The town described in contemporary documents has yet to be located. Historians have since realized that the metallurgist’s solid data on New World resources encouraged later skittish investors, who remembered Roanoke’s failure, to try again two decades later. Jamestown, located about 100 miles to the northwest, gave England its first firm foothold in the New World.

Those settlers searched in vain for valuable metals, but they did discover tobacco cultivation, and the weed became as valuable as copper, or even gold. Jamestown’s eventual success encouraged the Puritans to seek a home in the New World, and ultimately led to the formation of the American colonies and the United States. Yet the National Park Service has never commemorated the workshop or Gans at Fort Raleigh National Historic Site, its property devoted to telling the story of the Roanoke voyages.

“Here was an exceptional individual, whose efforts had not been recognized,” says Brent Lane, a heritage economist and history buff who was irked at Gans’ obscurity. He partnered with historian Leonard Rogoff of the University of North Carolina and applied to the state for a marker dedicated to the Prague scientist. “Gans really is a model for later generations,” adds Rogoff. “He was truly cosmopolitan; he is the perfect example of a globalized world of immigrants.”

State officials accepted the application. Motorists along Highway 64, the road running past the historic site, now can learn that Jews were an essential ingredient in the American experiment, long before 19th-century pogroms brought millions more to the United States. Such markers can be proposed and set up relatively quickly and cost effectively through the old-fashioned highway marker. Anyone can propose one, and there is typically no application fee.

That makes historical markers a surprisingly effective way to bring history to the people, particularly in small towns and rural counties where the past might otherwise be overlooked. Digital technology also is making it possible to read plaques even while whizzing by at 65-miles an hour. New phone apps allow drivers to hear the markers’ words spoken out loud, while websites like The Historical Marker Database enhance the online experience.

Comparing historical markers favorably to tweets, Lane argues that historical markers represent “a democratic way to curate history.” Given that the average marker has a price tag of around $2,500, it won’t bust tight state budgets. And the event or person commemorated doesn’t have to date back centuries. A sign went up in 2015 memorializing the massacre of five anti-Ku Klux Klan protestors in Greensboro, North Carolina, in 1979.

Such plaques increasingly provide needed context. New York City is adding signs to existing controversial monuments, such as the one to Christopher Columbus in Columbus Circle and to France’s Nazi-collaborating Marshall Petain on lower Broadway. “Reckoning with our collective histories is a complicated undertaking with no easy solution,” according to New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio. “Our approach will focus on adding detail and nuance to — instead of removing entirely — the representations of these histories.”

The furor over Confederate statues in high-profile places, such as courthouse steps and squares, is sure to continue, even if “explanatory” signs are added. But new historical markers can provide a fuller accounting of our history. The Gans marker may not heal deep-seated anti-Semitism, but the humble historical marker can be an important step in confronting–and celebrating–our shared past.