More than 2,000 years after Alexander the Great founded Alexandria, archaeologists are discovering its fabled remains

Trudging through swamp mud on a cold February day in 1608, Capt. John Smith and a small band of armed men approached a rickety wooden bridge. On the other side of a sluggish creek was the capital of the powerful Algonquian chief Powhatan, who ruled a vast territory across the Virginia tidewater. Smith, a canny mercenary who once did time as a Turkish slave, had reason to be wary. The first time he had seen Powhatan’s capital, two months before, he had been a captive. Only the intervention of Powhatan’s young daughter Pocahontas, as the English explorer would dramatize the scene years later, had saved him from execution.

This time, Smith was an invited guest at the Algonquian settlement, Werowocomoco. He was escorted by Powhatan’s son into the chief’s longhouse, built of saplings, reeds and bark and set apart from the village. He promised to help subjugate Powhatan’s enemies to the west, and Powhatan formally declared the pale-faced foreigner a weroance, or Algonquian chief.

The survival of Jamestown—established 400 years ago next month—hinged on this encounter at Werowocomoco. The English had unknowingly built their small rude settlement just a dozen miles from the center of Powhatan’s confederacy. In the midst of their first long winter, with insufficient food supplies, the foreigners were depending on exchanging copper ware, glass beads and iron hatchets for Algonquian corn. But the peace did not hold, and within a year Powhatan relocated his capital farther west. Werowocomoco was abandoned, and the location of the dramatic confrontations between Smith and Powhatan that ensured the English foothold in North America was lost to history.

Until Lynn Ripley got a dog.

Walking her Chesapeake Bay retriever on her York River property a decade ago, Ripley noticed potsherds sticking up from the clay. “They seemed to jump out at me,” she recalls in her garage turned laboratory as she opens a large safe and pulls out drawer after drawer of broken pottery, arrowheads and pipestems.

In 2001, two archaeologists who had visited Ripley told Randolph Turner at the Virginia Department of Historic Resources about her collection. Turner, also an archaeologist, has spent three decades trying to find Werowocomoco, poring over John Smith’s writings, examining a map of the site made by a Spanish spy in the English court and driving the back roads of Gloucester County looking for clues to its location. Even before hearing of Ripley’s finds, Turner’s search had led him to her long driveway, but he had never found anyone home.

When he saw her artifacts, he was convinced they came from the place where Powhatan ruled. For one thing, Smith had described Werowocomoco as situated on a shallow bay along the York River and bounded by three creeks within a mile of each other. “Everything fits—there’s no [other] place where it all comes together,” Turner says as we stand on the Ripleys’ pier surveying the creeks and river. “This is Werowocomoco.”

With the blessing of Lynn Ripley and her husband, Bob, Turner and other archaeologists set out in 2003 to uncover Powhatan’s town. They examined 20 small copper pieces, a cache larger than any ever found at a Native site in Virginia. The chemical signature of the copper matched that traded by Jamestown settlers between 1607 and 1609. Other metal items and glass beads found at the site also dated to the Jamestown era, as did at least one building.

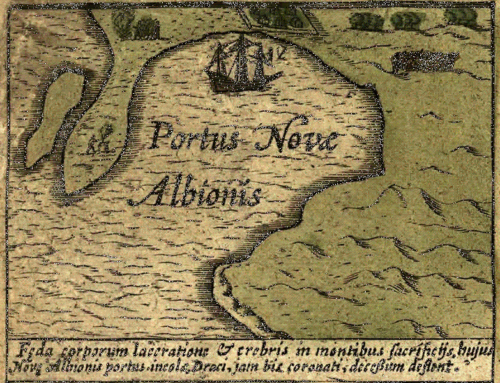

But most surprising were the faint remains of two great parallel ditches, each longer than two football fields. On the 1608 map made by Don Pedro de Zuñiga—the Spanish ambassador to England and a spy for King Philip III—is an odd double “D” shape at the site marked as Werowocomoco. The marking had been dismissed by many scholars as a misprint, but the archaeologists argue that it described the ditches, with the long stretches visible today forming the straight edges of the “Ds,” which then curved in an arc following nearby creeks. The ditches may have set off religious or ritual spaces from day-to-day activity. Radiocarbon analysis revealed that they were created in the 13th century—predating Jamestown by some 400 years.

Since historians long assumed that Powhatan founded Werowocomoco, the age of the ditches astonished archaeologists—and changed their understanding of Algonquian culture. They now believe that Powhatan, who came from a village to the west, placed his capital at what was already an ancient settlement.

Walking with me to the river’s edge, Martin Gallivan, an archaeologist at nearby William and Mary College, points out the spots—now green with new grass—where excavations first revealed an occupation centuries before Powhatan. “This was a big village,” he says, encompassing 45 acres. He estimates that hundreds of people may have lived here, working the fields and orchards that the digs show existed just inland.

On his 1608 visit, Smith and his men walked through the village and the fields, and then into the chief’s impressive residence. We know this because the explorer, with his eye for detail even in a moment of extreme tension, noted in his journal that the distance from the shore to Powhatan’s longhouse was “some thirtie score.” Accounting for erosion of the shoreline, Gallivan walked off about 1,500 feet—and found himself standing just inside the sacred area.

David Brown, a William and Mary graduate student working with Gallivan, is trying to make sense of a jigsaw puzzle of building post molds found in a large trench dug by the archaeologists. One of them has been radiocarbon dated to 1600. “We may have a structure here that is roughly 15 feet by 45 feet,” he says. Its large size, its location within the ditches and the shards of fine pottery and a fragment of copper found here hint that the building was part of Powhatan’s royal compound, though neither Brown nor Gallivan will go so far as to say this is the place where Smith met Powhatan and Pocahontas.

Smith and Powhatan parted friends after their winter meeting in 1608, but soon the two peoples would be locked in a spiral of violence that doomed Werowocomoco and ultimately Powhatan’s entire empire. Though he lived until 1618, the chief’s power would decline steadily. Oddly, the abandoned but fertile fields and orchards around the village do not seem to have immediately drawn English settlers. Perhaps a few Algonquians continued to live there or returned to bury their dead. “Or it may be a case of bad juju,” Brown says, speculating that whites might have been reluctant to inhabit an area once occupied by those they regarded as devil-worshiping savages.

Now, four centuries later, two of the archaeologists working at the site are Virginia Indians, several Native Americans have constructed a traditional house of saplings for education purposes, and a council of Virginia tribes keeps a close eye on the project to ensure proper treatment of any human remains. As Americans celebrate the 400th anniversary of the first permanent English settlement next month, it’s a good time to remember that earlier Americans had built a nearby village twice as old.

Andrew Lawler grew up just off Powhatan Avenue in Norfolk, a few dozen miles from Werowocomoco.