Long before today’s anxiety about terror attacks, Spain and England feared that enslaved Africans would be more susceptible to revolt if they were Muslim

(Wikimedia Commons)

On Christmas Day, 1522, 20 enslaved Muslim Africans used machetes to attack their Christian masters on the island of Hispaniola, then governed by the son of Christopher Columbus. The assailants, condemned to the grinding toil of a Caribbean sugar plantation, killed several Spanish and freed a dozen enslaved Native Americans in what was the first recorded slave revolt in the New World.

The uprising was quickly suppressed, but it prompted the newly crowned Charles V of Spain to exclude from the Americas “slaves suspected of Islamic leanings.” He blamed the revolt on their radical ideology rather than the harsh realities of living a life of slavery.

By the time of the Hispaniola revolt, Spanish authorities had already forbidden travel by any infidel, whether Muslim, Jewish, or Protestant, to its New World colonies, which at the time included the land that is now the United States. They subjected any potential emigrant with a suspicious background to intense vetting. A person had to prove not just that they were Christian, but that there was no Muslim or Jewish blood among their ancestors. Exceptions were granted solely by the king. Catholic Europe was locked in a fierce struggle with the Ottoman Empire, and Muslims were uniformly labeled as possible security risks. After the uprising, the ban applied even to those enslaved in the New World, writes historian Sylviane Diouf in a study of the African diaspora.

“The decree had little effect,” adds historian Toby Green in Inquisition: The Reign of Fear. Bribes and forged papers could get Jews to the New World with its greater opportunities. Slave traders largely ignored the order because West Africa Muslims often were more literate and skilled in trades, and therefore more valuable, than their non-Muslim counterparts. Ottoman and North Africans captives from the Mediterranean region, usually called Turks and Moors, respectively, were needed to row Caribbean galleys or perform menial duties for their Spanish overlords in towns and on plantations.

In the strategic port of Cartagena, in what is now Colombia, an estimated half of the city’s slave population were transported there illegally and many were Muslim. In 1586, the English privateer Sir Francis Drake besieged and captured the town, instructing his men to treat Frenchmen, Turks, and black Africans with respect. A Spanish source tells us “especially Moors deserted to the Englishman, as did the blacks of the city.” Presumably they were promised their freedom, although Drake was a notorious slave trader. A Spanish prisoner later related that 300 Indians—mostly women—as well as 200 Africans, Turks, and Moors who were servants or slaves boarded the English fleet.

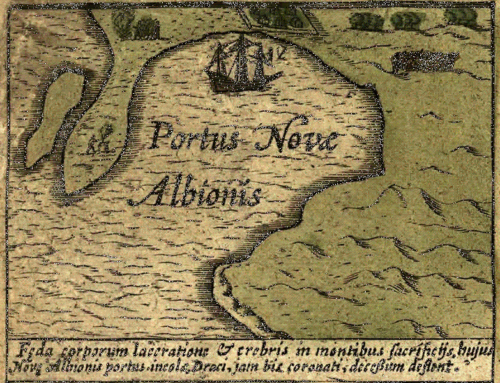

En route to the English colony on Roanoke Island, Drake and his fleet raided the small Spanish settlement of St. Augustine, on Florida’s Atlantic Coast, and stripped it of its doors, locks and other valuable hardware. With the pirated slaves and stolen goods aboard, Drake intended to bolster Roanoke, situated on the Outer Banks of North Carolina and the first English effort at settling the New World. “All the Negroes, male and female, the enemy had with him, and certain other equipment which had taken…were to be left at the fort and settlement which they say exists on the coast,” a Spanish report states.

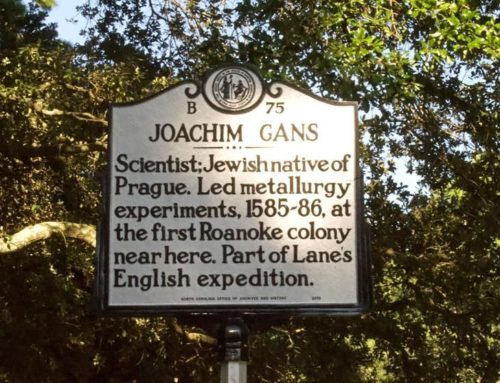

Drake sought to help his friend, Sir Walter Raleigh, who had settled Roanoke the year prior with more than 100 men and the goal of establishing a base for privateering and extracting the wealth that made Spain the richest and most powerful nation on Earth. Among them was a German metallurgist named Joachim Gans, the first Jewish-born person known to have set foot on American soil. Jews were forbidden to live or even visit England then—the ban lasted from 1290 to 1657—but Raleigh needed scientific expertise that could not be found among the Englishmen of his day. He won for Gans today’s equivalent of an H-1B visa so that the accomplished scientist could travel to Roanoke and report on any valuable metals found there. Gans built a workshop there and conducted extensive experiments.

Shortly after Drake’s fleet arrived off the Carolina coast, a fierce hurricane pummeled the island and scattered the ships. The English colonists abruptly chose to abandon their battered fort and return home with the fleet. Had the weather been more fortunate, the fragile settlement on Roanoke might have emerged as a remarkably mixed community of Christian, Jewish and Muslim Europeans and Africans, as well as Indians from both South and North America. The Drake fleet returned safely to England, and Elizabeth I returned 100 Ottoman slaves to Istanbul in a bid to win favor with the anti-Spanish sultan.

The fate of the Moors, Africans and the Indians, however, remains an enduring mystery. There is no record of them reaching England. “Drake thought he was going to find a flourishing colony on Roanoke, so he brought a labor supply,” says New York University historian Karen Kupperman. She and other historians believe that many of the men and women captured in Cartagena were put ashore after the storm.

Drake was always eager to make a profit from human or material cargo, and not inclined to liberate a valuable commodity, but there was little market in England for enslaved persons. To make room for the Roanoke colonists, he may well have dumped the remaining men and women on the Carolina coast and sailed away. Some of the refugees may have drowned in the hurricane.

Less than a year later, a second wave of English settlers sailed to Roanoke—the famous Lost Colonists–but they made no mention of meeting hundreds of refugees. The Cartagena captives might have scattered among the local Native American population to avoid detection by the slave raiders who prowled the North American coast in the 16th century. The new colonists were themselves abandoned in the New World and never heard from again—including Virginia Dare, the first English child born in America.

The Jamestown settlement that followed adopted a policy similar to that of the Spanish with regards to Muslims. Christian baptism was a requirement for entering the country, even for enslaved Africans, who first arrived in Virginia in 1619. In 1682, the Virginia colony went a step further, ordering that all “Negroes, Moors, mulattoes or Indians who and whose parentage and native countries are not Christian” automatically be deemed slaves.

Of course, suppressing “Islamic leanings” did little to halt slave insurrections in either Spanish or British America. Escaped slaves in Panama in the 16th century founded their own communities and fought a long guerilla war against Spain. The Haitian slave revolt at the turn of the 19th century was instigated by and for Christianized Africans, although whites depicted those seeking their freedom as irreligious savages. Nat Turner’s rebellion in Virginia in 1831 stemmed in part from his visions of Christ granting him authority to battle evil.

The real threat to peace and security, of course, was the system of slavery itself and a Christianity that countenanced it. The problem wasn’t the faith of the immigrants, but the injustice that they encountered on their arrival in a new land.