In Virginia, members of the Monacan tribe are embroiled in a battle over plans to build a water pumping station on a site they believe is their ancestral capital.

English explorer John Smith drew this detailed map of Virginia and the settlements of its Indigenous inhabitants in 1612. Monacan lands are at the top left. Smith didn’t visit the area but depended on intelligence from Native Americans. COURTESY NATIONAL PARKS SERVICE

IF TWO VIRGINIA counties have their way, a low-lying stub of forest jutting into the James River will host a small water pumping station to meet the needs of their growing populations.

But a determined coalition of Native Americans and preservationists have been battling the $10 million project, arguing that it would destroy Rassawek, the ancient capital of the Monacan tribe.

Today the National Trust for Historic Preservation announced that the embattled peninsula is one of the nation’s 11 most endangered historic sites. The listing is “final proof that the eyes of the nation are on the fate of Rassawek,” said Greg Werkheiser of Cultural Heritage Partners, the tribe’s legal counsel.

The tribe that wanted to be left alone

In 1607, just 10 days after English explorer John Smith and his fellow colonists settled at a marshy site they called Jamestown, an expedition went up the James River to search for precious metals. Their Native American guides, members of the Powhatan confederacy who spoke an Algonquian language, refused to take them beyond the falls at what is today Richmond. They explained that the Monacans who lived upstream were their bitter enemies.

A year later, a few English succeeded in making their way past the falls, but found the tribe uninterested in having any contact with the newcomers. Unlike the Powhatans, these people, who spoke a Siouan language, preferred to keep their distance. (Sequoyah was almost a Native American-governed state, until politicians folded Indigenous lands into Oklahoma.)

“Monacans resisted English settlement, trade, and political control for more than a century,” writes University of Virginia archaeologist Jeff Hantman in a recent book, Monacan Millennium. As a result, Europeans gained little knowledge of the Monacans’ traditions or language.

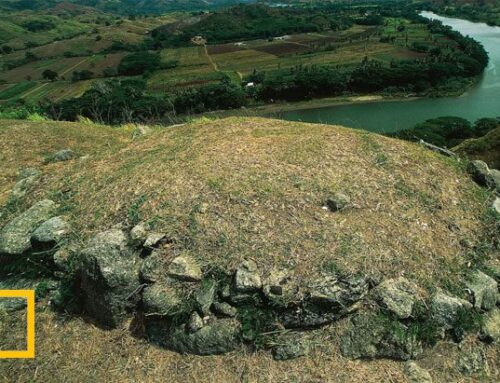

But Smith learned enough from Indian sources to include five of their principal villages on his famous 1612 map of Virginia. He located Rassawek on a peninsula where a substantial river converged with the James. Historians believe that river is the Rivanna, and that Rassawek today is known as Point of Fork, about 50 miles northwest of Richmond.

As colonists flooded in during the 17th and 18th centuries, the tribe abandoned their fertile lands along the rivers. Among those settlers was Thomas Jefferson, who built his famous Monticello estate upstream from Rassawek on ancestral Monacan land. He noted tribal members visiting their ancient burial mounds, and in 1783 excavated a 12-foot-high mound that held the remains of roughly a thousand men, women, and children laid down over several generations.

Some Monacans left the colony, while others moved into the Virginia backwoods. These were denied access to public schools and employment as late as the 1960s, according to Hantam. Not until 1989 did Virginia grant them state tribal status, and they won federal recognition only in 2018.

Today the Monacan tribe numbers more than 2,000 members spread across the country. Some 500 are centered in rural Amherst County, Virginia, just north of Lynchburg and 70 miles west of Point of Fork.

Reasserting rights

A decade ago, facing increasing development and decreasing groundwater, Louisa and Fluvanna counties asked the water authority to find a solution. The cheapest alternative proved to be siphoning water from the place where the Rivanna flows into the James. The next best alternative, said Justin Curtis, an attorney with AquaLaw representing the water authority, would nearly double the costs for two rural counties with limited revenues.

The James River Water Authority voted last month to consider other options to avoid disturbing the site. The authority is trying to think “outside the box,” Curtis said, and will announce its intentions in coming weeks. In the meantime, a completed $30 million water treatment plant on the opposite bank sits idle until a pump station is built, and new business and housing developments are on hold.

“We are in a sticky and tough spot, and there is no easy way out,” Curtis said. “We all acknowledge the site is historically important.” But, he adds, the location of Rassawek is still “open for debate.”

Hantman, who has spent more than three decades excavating western Virginia, calls that assertion “absurd.”

First, he notes that Smith was remarkably accurate in his map making. Second, he says that digs dating back to the 1930s have found a density of Native American artifacts, as well as Indigenous burials, leaving little doubt that the area around Point of Fork was Rassawek. Monacan Chief Kenneth Branham says that tribal members are convinced this was the site of their ancient capital. (Native American imagery is all around us—while Indigenous people are often forgotten.)

Curtis points out that the development would involve a house-size structure and a water pipe that would follow existing railroad, power, and pipeline routes, minimizing the impact on any ancient remains. He also says that the water authority had been working closely with the tribe since 2014, and that relations soured only two years ago, following the tribe winning federal recognition.

“Yes, they were talking to us off and on,” confirms Branham. “They were trying to buy us off.”

The water authority implied that the project was a done deal, Branham says, and that there were no other alternative routes. But after the tribe received federal recognition, some members discovered that the authority had in fact studied alternatives. They also learned that an archaeological survey of the area required by law was conducted by an unqualified contractor who hired unqualified workers.

“It is a good sign they’ve backed off” said Elizabeth Kostelny, director of Preservation Virginia, about the authority’s decision to put a hold on the project. “There is a history of Virginia Indians’ history being ignored. Multiple perspectives of history are necessary.” She added that while an alternative route may cost more, “once you do irreparable harm, there is no going back.”

In June, more than 12,000 individuals and organizations submitted comments opposing the plan to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which will make a decision on the building permit once the authority removes its hold. The Monacans intend to keep up the pressure.

“The longer it takes, the more they will recognize they need an alternative,” Branham said. “If not, we will take it to the Supreme Court.” Marion Werkheiser of Cultural Heritage Partners said if the authority proceeds with the Rassawek site, the tribe is prepared to sue both the Army Corps and the state of Virginia.

Branham hopes that once the battle is won, the water authority and local landowners might sell or donate land to create a wildlife reserve and protect Rassawek for future generations. “We don’t want to ever have this fight again,” he says.