Find provides “compelling evidence” to help solve one of America’s oldest historical mysteries.

Pieces of broken crockery recently unearthed in a North Carolina field belonged to survivors of the ill-fated Lost Colony, the first English settlement in the Americas. That dramatic claim has stoked a long-simmering debate over what happened to the 115 men, women, and children abandoned on North Carolina’s Roanoke Island in 1587.

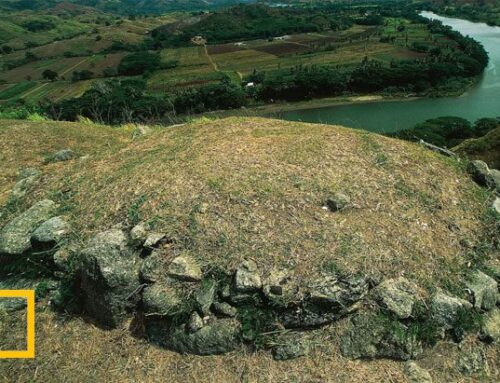

Working on a bluff overlooking Albemarle Sound, 50 miles west of Roanoke Island, a team from the First Colony Foundation uncovered a trove of English, German, French, and Spanish pottery pieces.

“The number and variety of artifacts recovered provide compelling evidence that the site was inhabited by several settlers from Sir Walter Raleigh’s vanished 1587 colony,” said archaeologist Nick Luccketti, the team’s leader.

The announcement came just months after another archaeologist claimed to have found objects related to the lost settlers on Hatteras Island, located about 50 miles south of Roanoke Island. If both discoveries hold up, they support the theory that the colonists split up into two or more widely separated survivor camps, almost certainly aided by Native Americans with whom they likely assimilated.

Clues to colonists’ fate

The Lost Colony was made up largely of middle-class Londoners who found themselves stranded on the North Carolina shore when the Spanish Armada attacked England, plunging their nation into war. At the time, the colony’s governor, John White, was in London gathering supplies and additional colonists. When he finally returned to the settlement three years later, he found it deserted.

The sole clue to the settlers’ fate was a post carved with the word “Croatoan,” then the name of Hatteras Island and its native inhabitants, who had been on friendly terms with the English. One of them, Manteo, traveled twice to England and was made a lord by Queen Elizabeth I.

White also wrote that the settlers intended to move “fifty miles into the main,” an apparent reference to an inland site. The governor never located the settlers, who included his daughter Eleanor Dare and his granddaughter, Virginia Dare, the first English child born in the New World.

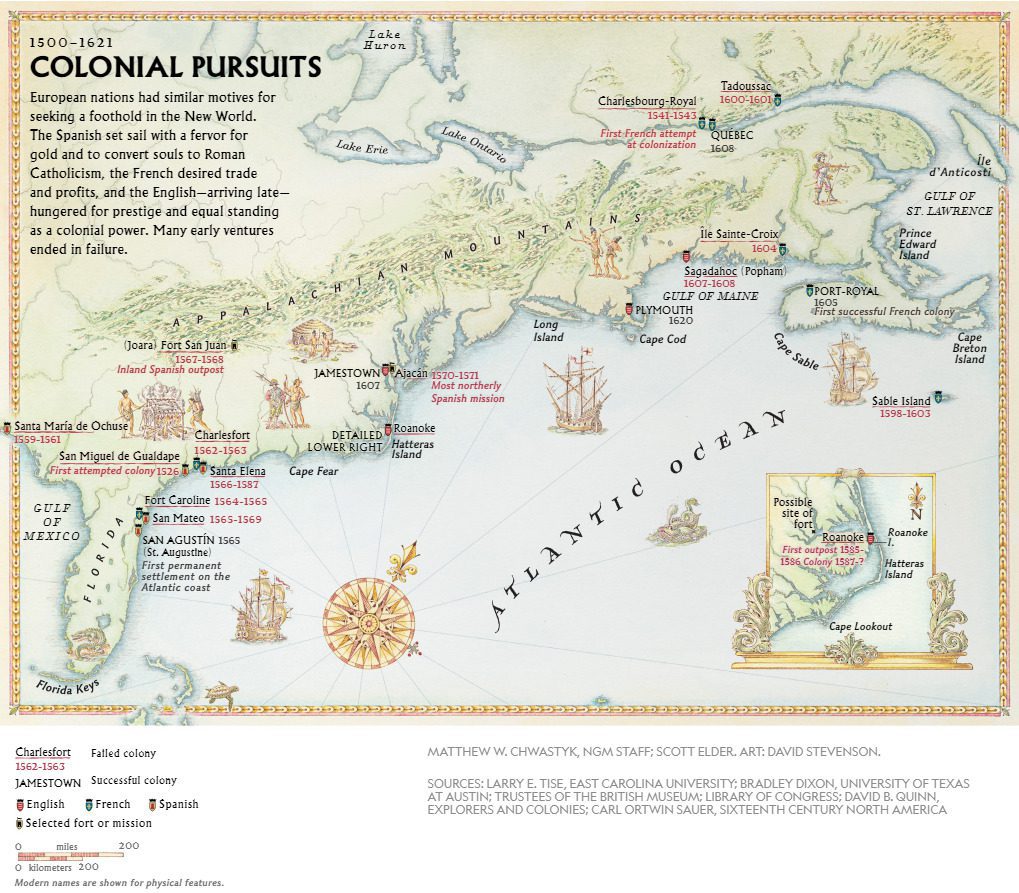

The case went cold until 2012, when researchers noticed a patch on a watercolor map of eastern North Carolina painted by White. Beneath the patch they found the image of a fort at the head of Albemarle Sound. Its location is 50 miles to the west of Roanoke Island, matching the governor’s account. On top of the patch was another faint outline of a fort, this one drawn in what analysts said was invisible ink.

Scholars speculated that White wanted to hide the existence of the fort from the Spanish, who viewed the Roanoke venture as a threat to their domination of North America and the critical shipping lanes off North Carolina’s Outer Banks. The Spanish sent an expedition to wipe out the rogue colony, but they, too, failed to find the settlers.

In 2015 Luccketti’s team excavated the area marked on the map, close to a Native American village called Mettaquem. Since early European colonists typically built their settlements near Native American sites, this seemed a good place to start.

Clay Swindell, an archaeologist associated with the First Colony Foundation who examined Mettaquem, said the palisaded village was home to some 80 to 100 people. Just outside its wall, at a place they called Site X, Luccketti’s team found no fort, but they did uncover two dozen pieces of English pottery that they maintained likely belonged to Lost Colony survivors.

In January, the archaeologists excavated in a field two miles north of Site X, which they dubbed Site Y. Here they found European ceramics in far greater number and variety than at Site X. Luccketti contends that at least some of the settlers moved from Roanoke after White’s 1587 departure, bringing along their European ceramics. He says that a small group, possibly a single family, may have taken up farming alongside their Native American neighbors as they waited in vain for rescue.

Mystery solved?

William Kelso, an archaeologist who led the effort to uncover the 1607 Jamestown fort, is confident the finds “solve one of the greatest mysteries in early American history—the odyssey of the Lost Colony.” Other archaeologists, however, warn against jumping to conclusions.

“I am skeptical,” says Charles Ewen, an archaeologist at East Carolina University. “They are looking to prove rather than seeking to disprove their theory, which is the scientific way.”

Luccketti’s assertion hinges on dating the small pieces of pottery—no easy task since styles remained the same for long periods of time. The ceramics at Site X and Site Y conceivably could have been left by later English traders who came from Jamestown, which was settled two decades after the failed attempt at Roanoke. Researchers agree, however, that the discovery of two separate caches strengthens Luccketti’s case.

“I have no problem with their interpretation of the ceramics in question as possibly late 16th century and potentially associated with the Lost Colony,” concludes Jacqui Pearce, a ceramic expert at the Museum of London. While all of the pottery continued to be made well in the 17th century, she says it seems unlikely this particular collection of pots was made after 1650, when the first known English traders began to infiltrate the area.

Still, the finds were mixed with soil plowed in subsequent centuries by later settlers and enslaved Africans, and the team has yet to find clear remains of an Elizabethan homestead. “One must find artifacts of known 16th-century date in a stratigraphically sealed context,” says Henry Wright, an archaeologist at the University of Michigan.

One intriguing clue that points to Roanoke colonists rather than Jamestown traders is the lack of early 17th-century clay pipes at Site X and Site Y. Early Roanoke expeditions appropriated pipe smoking from the Native Americans, and Raleigh made it fashionable in England. Slender clay pipes with small bowls, quite distinct from their indigenous counterparts in material and style, were inevitable parts of any English trader’s kit by the early 1600s.

But these pipes did not turn up at Site Y. Pearce called the absence of these significant. “If any of the inhabitants of the Lost Colony smoked, then they would have used native pipes rather than London-made ones,” she said.

Second survivor camp?

While Luccketti’s team was digging at Site X, a group led by Mark Horton, then an archaeologist at the University of Bristol, was excavating the remains of a Native American village on today’s Hatteras Island, the historical Croatoan. Working with volunteers from the Croatan Archaeological Society, he uncovered European artifacts, including the hilt of a 16th century rapier and part of a gun.

Scott Dawson, head of the society, said the artifacts provide evidence that the colonists assimilated with the Croatoan people. “We now know not just where they went but also what happened after they got there,” he wrote of the colonists in a recent book.

Horton, who has not yet published his finds, cautioned that these objects were all found in a context dating from the mid- to late-17th century. That means they might be heirlooms passed down by the descendants of the colonists, or later trade goods obtained from Jamestown.

Luccketti doubts that large numbers of Roanoke colonists descended on Croatoan, in part because environmental evidence indicates that rainfall was scarce in the decade following the settlers’ arrival. “You don’t just dump a hundred people on an island in a drought,” he said.

But Horton said the discoveries from Site X, Site Y, and Hatteras give credence to the increasingly popular theory that the Lost Colonists went their separate ways and merged into the local Native American communities. “This is typical in situations like shipwrecks,” he says. “Order breaks down and you end up with several survivor camps.”

And there is a clear precedent. In 1586, when food ran perilously short for members of the first Roanoke colony, its leader dispersed his hundred settlers across the region, including to Croatoan, so they could forage—a tactic that proved successful until they could hitch a ride back to England.

Dawson hopes to resume digs on other parts of Hatteras in the search for a survivor’s camp, while Luccketti’s team also intends to continue their hunt. “There is not enough data, but they should keep looking,” says Ewen.