Researchers zero in on a little-known landscape that offers some chilling lessons on the future of global warming.

|

| Scientists say Greenland’s glaciers are melting twice as fast as they were even five years ago, and that the amount of fresh water running into the ocean has tripled in a decade. Photos by Nick Cobbing | Still Pictures/Peter Arnold Inc. Courtesy Greenpeace International |

|

| Tourists frequently visit this glacier near Narsaq. The underlying ice core is visible in the bright blue patches, which are exposed as chunks calve from the glacier, forming icebergs when they hit the fjord. Photos by Nick Cobbing | Still Pictures/Peter Arnold Inc. Courtesy Greenpeace International |

|

| Although melt lakes have long been common on Greenland’s ice cap, their size and frequency show signs of increasing. Only now are scientists closely monitoring this development. Photos by Nick Cobbing | Still Pictures/Peter Arnold Inc. Courtesy Greenpeace International |

|

| Focusing on Narsaq, Greenland, where global warming is an everday affair. Photos by Nick Cobbing | Still Pictures/Peter Arnold Inc. Courtesy Greenpeace International |

Let’s face it. Look on any world map and Greenland is pretty nondescript, a featureless white plain neatly bordered by a rocky fringe. Although scientific papers may dutifully warn us that Greenland’s ice sheet is melting, for most of us the enormous island remains distant and abstract. But while leaning out of a small helicopter, photographer Nick Cobbing encountered a landscape that was more visceral, beautiful—and terrifying. In this Greenland, the surface is anything but featureless. It cracks, bows, and trembles.

A glacial pace becomes a trot, then a torrent. Huge unnamed lakes emerge silently in a thaw that is remaking the landscape.

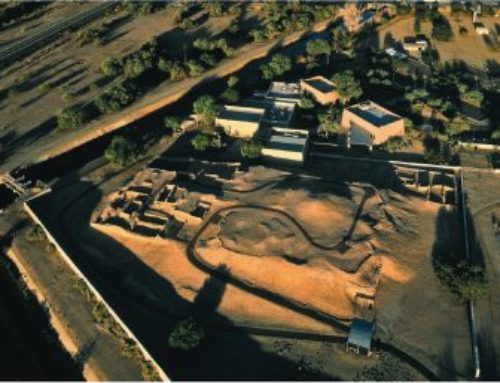

Today researchers are closely monitoring Greenland’s harsh and uncharted environment, forming an astonishingly detailed view of this remote land that is an epicenter of global warming. Cobbing visited the island as part of a 2005 Greenpeace expedition to gather scientific data and the testimonies of local people on the changes now reshaping Greenland. His job was to document the melt lakes that increasingly dot the ice cap during the summer months. On its two-month cruise the Greenpeace icebreaker Arctic Sunrise worked its way deep into Greenland’s fjords, providing a launchpad for helicopter surveys far inland and good access to the remote interior. Still, the actual photography was, to say the least, physically challenging. Shooting from “a rattling, doorless 1970s helicopter about 2,000 feet above only broken ice and meltwater, days away from any possibility of rescue, is scary,” says Cobbing, who was strapped in and guided by a veteran pilot. “You knew if you pitched down, no one was going to get you.”

Such expeditions in the summer months are increasingly common, and automated American and Dutch research stations now dot the central plateau to gather data year-round. Next year Danish scientists will start constructing a similar automated network along the coasts. Combining data gleaned from expeditions, robotic stations, and orbiting satellites, they hope to judge precisely how quickly Greenland’s ice cap—an area almost as large as Mexico—is melting, and how it will shed its icy skin. Answering those questions is far from some abstract exercise. Were Greenland to lose its covering tomorrow, the world’s seas would jump about 20 feet, drowning nearly every major coastal city on earth.

Even if a disaster of this proportion is not in the cards, in the past decade melting began to accelerate ominously. The area now actively melting—approximately half of Greenland’s entire ice cap—is twice what it was in 1992. The amount of fresh water entering the ocean is triple what it was a decade ago. Last year Greenland lost 52 cubic miles of ice, according to NASA measurements, and though that is only a tiny fraction of the ice cap’s total of nearly 600,000 cubic miles, the rate is increasing. As the meltwater drips down to the bedrock, it lubricates the movement of ice sheets toward the sea. The Kangerdlugssuaq Glacier, on the island’s eastern coast, is now moving twice as fast as it was in 2002. To the south of Kangerdlugssuaq, the Helheim Glacier slides about 110 feet a day. Researchers reported this spring that the speed and intensity generates noticeable earthquakes, or “glacial quakes.” And some scientists quietly worry that a dramatic collapse of the ice cap could result in huge amounts of water draining into the ocean.

For the 38-year-old Cobbing, the chance to hover over Greenland’s interior offered an unusual, if harrowing, glimpse into both a climatic and a geographic unknown. “Flying with the doors off is bloody scary,” he says. “But it did give us 180-degree views.” These photos, culled from that trip, finally put Greenland on the map, in a fresh and chilling way. —Andrew Lawler