A long-buried street that led pilgrims to the Jewish Temple 2,000 years ago was commissioned by Roman governor Pontius Pilate.

To uncover an ancient stepped street in Jerusalem, Israeli archaeologists and engineers are building what resembles a subway tunnel under a Palestinian neighborhood. PHOTOGRAPH BY SIMON NORFOLK, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

PONTIUS PILATE IS a man many Jews and Christians love to hate. For Christians, the Roman governor of Judaea played a central role in the execution of Jesus around A.D. 30, while for Jews he was a callous ruler who set the stage for the rebellion that led to the destruction of Jerusalem four decades later.

But a new discovery suggests that Pilate also spent a good deal of time and money embellishing the famous city that drew Jewish pilgrims as well as visitors from around the Roman Empire.

Archaeologists tunneling beneath a Palestinian neighborhood just south of Jerusalem’s walls are uncovering a monumental stepped street that led to the foot of the Temple Mount, the sacred platform that once held the Jewish Temple and now is home to some of Islam’s holiest sites.

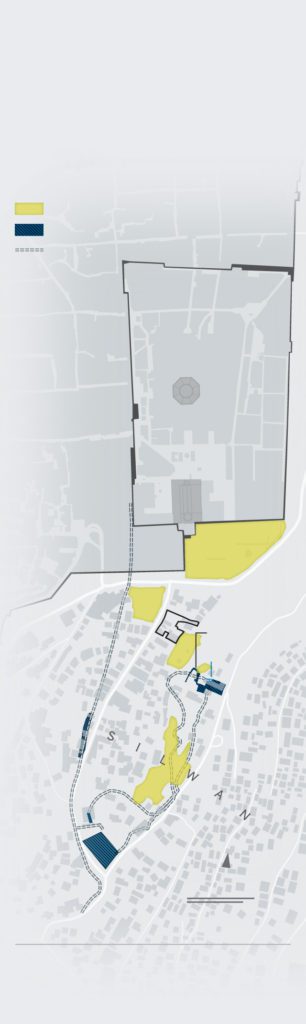

ALBERTO LUCAS LÓPEZ, MATTHEW W. CHWASTYK, AND KAYA BERNE, NGM STAFF; PATRICIA HEALY SOURCES: JOE UZIEL, IAA; JODI MAGNESS, UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA AT CHAPEL HILL; OPENSTREETMAP CONTRIBUTORS, AVAILABLE UNDER OPEN DATABASE LICENSE

The impressive walkway stretched more than a third of a mile, was 26 feet wide, and required some ten thousand tons of limestone slabs. “We think it was a single project built at one time,” says Joe Uziel, the Israel Antiquities Authority archaeologist in charge of the effort. Uziel and his colleagues recently published their findings in Tel Aviv: Journal of the Institute of Archaeology.

Historians long assumed that the Roman-appointed King Herod the Great, who died around 4 B.C., was responsible for most of the great construction efforts that transformed ancient Jerusalem into a major pilgrimage and tourist center. But analysis of more than 100 coins found beneath the stepped street point to the start and completion of the effort under Pilate, who ruled for about a decade starting in A.D. 26 or 27.

The latest coins discovered beneath the paving stones date to around A.D. 31. The most common Jerusalem coins from the first century were minted after 40, “so not having them beneath the street means the street was built before their appearance, in other words only in the time of Pilate,” says Donald Ariel, a coin expert with the Israel Antiquities Authority.

Pilate served under Emperor Tiberius, and contemporary writers mention incidents in which the governor incited Jewish anger by ignoring the taboo on graven images, and incurred the people’s wrath for stealing Temple funds to pay for a new aqueduct. (See maps that imagine what Jerusalem looked like in the time of Jesus.)

The Christian Gospels also accuse the governor of ordering the Crucifixion of Jesus, likely on charges of sedition. The Roman-Jewish historian Josephus contends that Pilate was removed by the emperor for ordering an attack on Samaritans in the north of Judaea and returned to Rome in disgrace. (Meet the high priest behind Jesus’s rushed trial.)

Tel Aviv University archaeologist Nahshon Szanton, the lead author of the study, speculates that Pilate’s construction of the street “may have been to appease the residents of Jerusalem,” as well as to “aggrandize his name through major building projects.” In A.D. 70 the street was buried under rubble following a revolt between Jewish groups that led to the Roman destruction of the city. Many of its slabs were subsequently reused for later projects.

Matthew Adams, director of Jerusalem’s W.F. Albright Institute of Archaeological Research, who was not involved in the work, says the results provide insight into the time when Rome exerted direct control over Judaea. “It also provides some evidence of cooperation between the Roman authorities and the Jewish religious authorities,” he adds, noting that most known sources emphasize tension between the two.

But Jodi Magness, an archaeologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, is not wholly convinced. “The material they are finding is coming from fills that might have been brought in with wheelbarrows from anywhere, so I’m skeptical of the dating,” she says. “It is not impossible that Pilate was responsible for the construction, but that is not the only, or even the most likely, possibility.”

Magness is also critical of the method used to unearth the stepped street. Instead of digging from the surface down, excavators are boring a subway-size tunnel to expose the street. “You don’t have context—you can’t see what’s above or to the side. It’s unacceptable.”

Uziel argues that tunneling was necessary, given the densely populated neighborhood above, and that the team is able to collect careful stratigraphic information.

The effort, funded in large part by a Jewish organization called the City of David Foundation, has drawn international criticism for its location as well as methods. Palestinians living and working in this East Jerusalem area complain about damage to their homes and businesses from the digging, while the central focus on a famous period of Jewish history has irked others. The Palestinian Authority decried the tunnel as part of a plan to “Judaize” East Jerusalem, which it and much of the rest of the world considers occupied territory.

During a ceremony last June inaugurating part of the tunnel, U.S. Ambassador to Israel David Friedman dismissed these concerns. The project, he said, “confirms with evidence, with science, with archaeological studies that which many of us already knew, certainly in our heart: the centrality of Jerusalem to the Jewish people.”

And, if the science proves correct, it was a despised Roman who helped make it a city renowned across the empire for its holy sites and monumental architecture.