The boulevard that long defined Richmond, Virginia, capital of the Confederacy, began as a ploy by a savvy real estate developer.

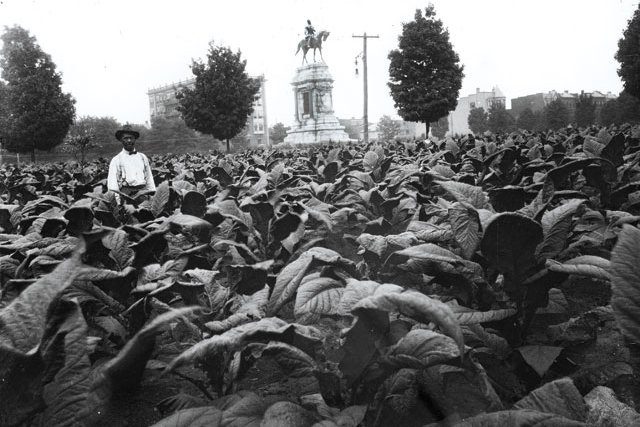

A monument to Confederate General Robert E. Lee was erected in 1890 next to a tobacco field planted as an exhibition garden of Virginia’s leading cash crop. The statue gradually became the center of a fashionable all-white neighborhood along Richmond’s tree-lined Monument Avenue. PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY COOK COLLECTION, THE VALENTINE

Empty plinths colorfully spray-painted with social justice slogans now punctuate the South’s grandest boulevard. In the aftermath of the May 25 killing of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police, protestors and city contractors brought down the immense memorials to Confederate leaders along Richmond’s tree-lined Monument Avenue.

“Times have changed, and removing these statues will allow the healing process to begin,” said Levar Stoney, the city’s 39-year-old African-American mayor. “Richmond is no longer the capital of the Confederacy. It is filled with diversity and love for all.”

Yet the 12-ton equestrian figure of General Robert E. Lee continues to tower over one of the Virginia capital’s most elegant neighborhoods, its fate tied up in litigation. The statue celebrates the leader of Confederate forces, but its origin reveals a bitter struggle between his nephew and a biracial coalition to define the New South in the aftermath of the Civil War.

As Union troops approached the beleaguered city in April 1865, Confederate soldiers set fire to its warehouses, and the conflagration eventually destroyed a quarter of Richmond. The city was slow to recover, but by the early 1880s its factories boomed, drawing Black, white, and immigrant workers. An impressed New York Times lauded Richmond’s “snap and go” that heralded “a new epoch” of commercial ambition.

That new epoch brought political change as well. An alliance of white, working-class Democrats and Black Republicans formed a powerful movement called the Readjusters, a term referring to those who wanted to renegotiate Virginia’s pre-war debt in order to invest in the future. Its leader was William Mahone, an industrialist who had served with General Lee.

The Readjusters quickly won control of the state’s general assembly, the governorship, and municipalities like Richmond, and launched an ambitious effort to boost funding for schools for both Blacks and whites and abolish laws designed to discourage Black voting.

Conservative Democrats resolved to break this formidable alliance by reviving the fading passions for the Lost Cause. Fitzhugh Lee, who had fought under his uncle in the Civil War, led the charge. By 1885, Lee was in the governor’s mansion, and the Democratic Party regained the legislative majority, though a few cities, like Richmond, remained Readjuster strongholds.

Governor Lee made erecting a monument to his uncle a priority, in order to keep the fires of Confederate memory kindled. In 1886 the general assembly put him in charge of a memorial association, and his agents fanned out across the South to solicit donations. The ideal emissary, one of the governor’s secretaries confided, was a handsome but “crippled, maimed Confederate” who could “interest the women.” Contributions poured in. (Here’s why the Confederate battle flag made a 20th century comeback.)

The city’s leading white women advocated a prominent downtown hill as the best site for the equestrian statue, which was cast in Paris at a cost of $77,500. The governor had other ideas. One of his close friends, a real-estate developer named Otway Allen, proposed donating a lot in a field a quarter mile west of the city limits. Allen envisioned the statue as the magnet to create a fashionable—and lucrative—subdivision.

The proposal drew outrage across the state for seeming to trade on the dead general’s prestige for financial gain. A Lynchburg newspaper accused the association “of betraying its high public mission in favor of crass private interests” by relegating the statue to “a remote and inaccessible suburb.”

Whether Lee’s nephew stood to benefit directly from the deal is not clear, said University of Pittsburgh historian Kirk Savage. But the governor brushed aside the clamor, arguing that the plan would increase tax revenues for the fast-expanding city. Yet when he sought $15,000 from the Richmond city council in the fall of 1887 to cover the cost of a celebration at the laying of the cornerstone, he met spirited resistance.

One city council member dismissed the project as “merely an effort to boom an old field,” while two African-American council members openly ridiculed the request. “If I had a different complexion, I would vote for the appropriation,” joked Anderson Hayes, drawing laughs from the audience. “General Lee was a good man, and I hope he is at rest,” added Edinboro Archer. “He had his opinions and I have mine.” In the end, the request was soundly rejected 17 to 8.

The cornerstone nevertheless was laid, and the May 1890 dedication was timed to coincide with a massive Confederate veterans’ reunion that drew 50 former generals, 15,000 uniformed veterans, and more than 100,000 onlookers. By then, an ominous new era of white supremacy had dawned that would last seven decades. (Related:Today’s toppling of Richmond’s statues is the first step toward ending Confederate myths.)

When the governor sought $7,500 from the city to help cover the cost of the ceremony, the three remaining African Americans on the council found it prudent to abstain rather than vote for the measure, which easily passed. Soon after, the Democrats gerrymandered the largely African-American ward that they represented out of existence, effectively removing Blacks—and therefore nearly half of Richmond’s population—from city leadership. That was just the start. African Americans across the state subsequently were largely disenfranchised and subject to a battery of new laws enforcing strict segregation.

“Few doubt that in the course of five years the Lee circle will be in the very heart of the fashionable neighborhood of Richmond,” a newspaper reported around the time of the dedication. When novelist Henry James visited in 1905, however, he compared the general’s figure to “some precious pearl of ocean washed up on a rude bare strand.” Over time, however, the subdivision became an exclusive and wealthy enclave where African-American residents were prohibited.

After the Lee dedication, new Confederate monuments sprang up in the city “with something akin to a vengeance,” wrote historian Kathy Edwards. Along what was dubbed Monument Avenue, statues of General “Jeb” Stuart and Confederate President Jefferson Davis were unveiled in 1907. General Stonewall Jackson took his place in 1919, followed a decade later by Confederate Navy chief Matthew Fontaine Maury. By then the boulevard had emerged as what historian Charles Reagan Wilson called “the sacred road” of “Southern civil religion.” Its only addition came in 1996, when a statue of African-American tennis pro and Richmond native Arthur Ashe was erected.

Floyd’s death abruptly changed all that. By July 2, four of the five Confederate memorials were in storage behind the fence at Richmond’s wastewater treatment plant. “For too long, we have overlooked the inherent racism of these monuments, and for too long we have allowed the grandeur of the architecture to blind us to the insult of glorifying men for their roles in fighting to perpetuate the inhumanity of slavery,” the Monument Avenue Preservation Society said in a statement supporting the eviction. (As monuments fall, the world reckons with which relics to preserve—and which to remove.)

Yet Lee remains. His memorial rests on land given by private owners to the state on the condition that “she will faithfully guard it and affectionately protect it.” In June, a great-grandson of one of those owners sued to force Virginia to keep that promise, though the state’s attorney general called it “a grandiose monument to a racist insurrection” that was “designed to demean Black Virginians” and should be taken down. For the moment, a court injunction prevents that. On July 23, a Richmond judge said he would soon issue a written opinion on the fate of Fitzhugh Lee’s creation.