BOOK AUTHOR | MAGAZINE WRITER | TRAVELER

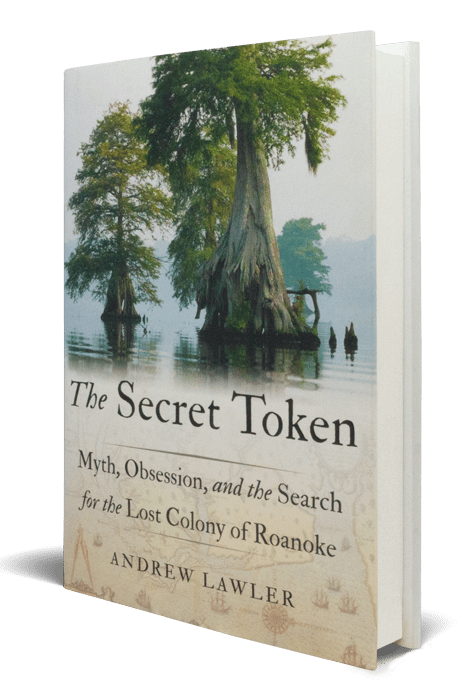

ANDREW LAWLER

“Just plain fascinating”

–The Washington Post

“A book that is hard to put down”

–American Archaeology

“A lively and engaging read”

–The Economist

“A thoughtful and timely discourse about race and identity”

–Publishers Weekly

“The most authoritative account of the Lost Colony to date, if not the last word”

–Wall Street Journal

“[An] enjoyable historical adventure”

–Kirkus

Order The Secret Token at these booksellers, or visit your local bookstore!

“Just plain fascinating”

–The Washington Post

“A book that is hard to put down”

–American Archaeology

“A lively and engaging read”

–The Economist

“A thoughtful and timely discourse about race and identity”

–Publishers Weekly

“The most authoritative account of the Lost Colony to date, if not the last word”

–Wall Street Journal

“[An] enjoyable historical adventure”

–Kirkus

Order The Secret Token at these booksellers, or visit your local bookstore!

BOOK AUTHOR | MAGAZINE WRITER | TRAVELER

ANDREW LAWLER

“Just plain fascinating”

–The Washington Post

“A book that is hard to put down”

–American Archaeology

“A lively and engaging read”

–The Economist

“A thoughtful and timely discourse about race and identity”

–Publishers Weekly

“The most authoritative account of the Lost Colony to date, if not the last word”

–Wall Street Journal

“[An] enjoyable historical adventure”

–Kirkus

Order The Secret Token at these booksellers, or visit your local bookstore!

REVIEWS

The Washington Post

The Washington Post

The lost colony of Roanoke Island will always be one of the weirdest episodes in American history. It has managed to stay in the news, off and on, for 431 years: the case of 100-plus English settlers vanishing in the woods and marshes of coastal North Carolina. But most Americans who know the basic mystery have no idea of the deep, tantalizing layers of strangeness that underlie almost every aspect of the tale.

Things were off-kilter from the beginning. Sir Walter Raleigh had bankrolled a settlement for the shores of the Chesapeake Bay. But when the ship containing some 115 settlers arrived in the New World in July 1587, the captain and pilot mysteriously dumped them at Roanoke Island instead. Tucked behind today’s Outer Banks, the island was reachable through some of the most dangerous waters of the East Coast. The native inhabitants had already been insulted and mistreated by other Englishmen, so this wasn’t the most welcoming location.

The man Raleigh chose to lead the colony, John White, was an artist, not an explorer. He brought his pregnant daughter and her husband. A few weeks after landing, daughter Eleanor gave birth to the first English baby born in America, Virginia Dare. At which point White — who was supposed to be running things — sailed all the way back to England to ask for more supplies.

He didn’t return for three years. By then, the settlers were gone. There were intriguing clues to their whereabouts carved on a tree and a post, including the name of a nearby native village. But rather than check that out, White sailed again for England.

And the colony has been lost ever since.

It’s human nature to wonder what happened to those men, women and children. Capt. John Smith tried to figure it out after arriving at Jamestown in 1607. But it seems that every effort to solve the mystery has spun out strange tendrils of its own.

Andrew Lawler warns in his new book, “The Secret Token: Myth, Obsession, and the Search for the Lost Colony of Roanoke,” that Lost Colony fever is a kind of madness. Happily, that doesn’t stop him from plunging into the wild terrain of theories and conflicting evidence where so many others have disappeared. Lawler manages to do this in a clear-eyed way, conscious of whether he, too, is getting lost. He makes a good case that the search itself goes to the heart of what it means to be American. Plus, it’s just plain fascinating.

As a writer for Science magazine, National Geographic and Smithsonian, Lawler has a polished, pop-history writing style — informative without seeming dense, entertaining but not pandering.

One of the strengths of the first section of the book is its depiction of the civilizations that had already been clashing for generations when Raleigh sent out his settlers. Not only were the sophisticated nations of native peoples disrupted by European colonization, but the Spanish had explored and settled along the East Coast for decades before the English arrived. The city of St. Augustine, Fla., boasted 250 houses more than a century before any English colony could claim such a number.

One of Lawler’s most fascinating points — which he touches on too briefly — is that the English pirate Sir Francis Drake may have left a large group of formerly enslaved workers on the Carolina coast in the year before the Lost Colony. Drake had captured the Africans and native South Americans during a raid on the Spanish port of Cartagena. If he left them at Roanoke, as some accounts suggest, they would “form a mysterious other lost colony,” Lawler writes. “Their presence on Roanoke would mean that the bulk of the first permanent settlers of England’s initial New World colony were neither Christian nor European but North African Muslims as well as followers of West African and South American traditions.”

Lawler also does a good job conveying the strangeness of one of the central figures of the Lost Colony mystery: the wayward governor, John White. After describing White’s return to find the colony abandoned and no sign of his daughter or granddaughter, Lawler puts his finger on something that by now has been nagging at the reader. “The record White left behind has a hallucinatory quality unlike almost anything in early American literature,” Lawler writes. “Bonfires ignite as if by ghosts. There are footprints in the sands of a silent forest. . . . There is an otherworldly detachment to his tale, as if the governor were a disembodied witness rather than the main character in an emotionally wrenching journey.”

He’s right. White’s narrative seems like a surreal dream. It brings to mind another strange account of adventures: Edgar Allan Poe’s novel “The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket,” which reads as though written by someone who never traveled the seas and made it up as he went along. Possibly while taking laudanum.

So, what does it all mean? That’s part two of the book, where Lawler tries to mop up the historical mess with centuries of theories about what really happened. He roams from John Smith’s sighting of white children among the Indians, to the mid-20th-century craze for messages supposedly left on stones by Eleanor Dare, to the collection of misfits and competing scholars who toil away at the question today.

It’s frustrating stuff. Every idea that seems to have merit — complete with secret details discovered on ancient maps — either evaporates or remains unresolved. There have been intriguing recent developments, but we won’t spoil some of the book’s juicy tidbits.

Though he presents himself as a skeptical arbiter who will hold any charlatans accountable, Lawler falls into the habit of ending chapters with suggestive cliffhangers. It works, for a while, but gets distracting.

The third and final section of the book aims for a cultural reckoning with the legacy of the Lost Colony. The heavier tone — who knew that Virginia Dare was once a symbol for white supremacists? — is a bit of a comedown after the crazy fun of the conspiracy theories.

But the themes of mingled races, of cultures clashing to create something new, are surprisingly fresh and powerful. The issues raised by the Lost Colony are still playing out. It’s a mystery in which all Americans have a stake.

The Wall Street Journal

The Wall Street Journal

‘Would to God my wealth were answerable to my will,” despaired John White in 1593, having been forced to sail back to England, never again able to return to the Outer Banks of North Carolina to search for the “Lost Colony” of men, women and children marooned 4,000 miles from home. Not for four centuries would anyone make a systematic effort to resume the hunt.

The narrative of America’s oldest mystery unfolds between 1584 and 1590. Over the course of three voyages backed by Sir Walter Raleigh, two dozen vessels and more than 1,000 people crossed the Atlantic trying to establish England’s first permanent New World settlement. Ambitions ran high. In cost and scale, the voyages far exceeded later efforts by the Jamestown settlers and the Pilgrims of Plymouth. “It was the Elizabethan equivalent of the Apollo program,” writes Andrew Lawler in “The Secret Token.” Yet, unlike later ventures, Roanoke was a dismal failure.

After an exploratory expedition of the Carolina coast, some 100 men disembarked in 1585 on a small island within the Outer Banks, only to desert their primitive fort for England when fresh supplies from home didn’t arrive. In 1587 a second attempt landed 118 settlers, including 17 women and 11 children, followed soon afterward by the birth of Virginia Dare, the granddaughter of the colony’s governor, John White.

The rest is well-known. At the colonists’ urging, White returned to England later in 1587 to organize a re-supply mission, but the Battle of the Spanish Armada, pirates off Morocco and harsh weather all thwarted his return until August 1590, when he found Roanoke deserted and its makeshift houses dismantled. The only clues were letters carved into a tree (“CRO”) and a post with an inscription in capital letters (“CROATOAN”). Missing was the emblem of a cross, “a secret token” that the colonists had earlier agreed to leave, if necessary, as a sign of distress.

“The Secret Token,” spanning more than 400 years, offers the most authoritative account of the Lost Colony to date, if not the last word. After describing the failed attempts to establish a beachhead, Mr. Lawler jumps from the 1580s to the 20th century, when fortune hunters tried to resolve the colonists’ fate. Amateur sleuths, genealogists and gold diggers joined the quest—as did con artists, resulting in the sensational “discovery,” in 1937, of a large stone about 60 miles to the west of Roanoke Island. Inscribed on it were not only a cross but also the words of Gov. White’s daughter, Eleanor Dare, lamenting the deaths in 1591 of her husband and the infant Virginia at the hands of Indians.

The “Dare Stone” captured far-flung attention, from university geologists to President Franklin Roosevelt, who visited Roanoke Island and commissioned a commemorative stamp in celebration of Virginia Dare’s birth. Notwithstanding the persistence of true believers, the stone proved to be a hoax, as did subsequent “Dare” gravestones located in South Carolina by a Georgia stonecutter. No artifacts were ever found at the supposed site of the “Dare Stone”—or, for that matter, any subsequent trace of the California couple whose discovery first ignited the frenzy.

Today, rather than Roanoke Island, two spots have excited historians and archaeologists as plausible destinations of the lost colonists. No longer is it thought likely that they migrated to a location in Virginia just south of the Chesapeake Bay. Instead, if they didn’t fall victim to hostile Indians, starvation and sickness, a clutch of survivors or perhaps the entire company may have trickled south to Croatoan (today known as Hatteras Island), where fish and oysters were abundant and the natives were thought to be friendly. John White himself in 1590 had believed this their likely destination from the clues left on Roanoke. Excavation of a site at Cape Creek on Hatteras Island began in 1995, netting a copper signet ring and a rusted rapier, among other tantalizing artifacts. All, however, were of uncertain provenance.

Alternately, in 2012 the discovery of an “X” beneath a patch of paper on an early map of North Carolina in the British Library received widespread publicity, supposedly for disclosing a site lying at the head of the Albemarle Sound, 50 miles west of Roanoke. (Like Croatoan, it would have afforded a central spot for viewing arriving ships.) But digs have yet to yield little more than shards of English pottery of indeterminate age.

“You look lost,” a bartender on Roanoke Island said to Mr. Lawler as she poured him a beer. After months of trudging through swamps and dense underbrush, grappling with misleading claims—to say nothing of ticks, mosquitoes and poison ivy—the author might be forgiven his confusion. In truth, he recounts his arduous travels with clarity and insight.

This much seems possible, perhaps even likely (precious little is certain about the Lost Colony): Bands of colonists may have ventured to both Hatteras Island and Albemarle Sound and joined natives by whom they were assimilated. This theory, in fact, was first publicized in 1834 by the famous historian George Bancroft. Mr. Lawler even speculates that the survivors, embraced by their newfound families, may have hidden upon Gov. White’s return, preferring, in short, to “remain lost.”

It is tempting to exaggerate the enduring fascination of the ill-starred English colony. Occasionally the author overreaches in stressing its “powerful grip” on our imaginations and, in particular, the attraction of Virginia Dare, America’s first offspring of English descent, who over the years has been adopted by movements as disparate as feminists and white supremacists. “This is a haunting as much as history,” the author asserts, “a spooky tale reinterpreted by each generation to reflect our current national dreams and anxieties.”

In Mr. Lawler’s case, his notions of the New World as a multicultural melting pot come closer to reflecting current conceptions of “social justice” than do traditional stories of massacres and mayhem. Would that his vision had been so.

The Economist

The Economist

The tale of the “Lost Colony” is a 400-year chronicle of madness and delusion. As Andrew Lawler recounts in “The Secret Token”, it begins in 1587 with the ill-conceived, ill-executed attempt to found the New World’s first English settlement on Roanoke Island, and continues to this day in the obsessive quest to discover how and why the colony disappeared. Both the original settlers and those who, over the subsequent centuries, have quixotically tried to trace them seem equally deluded. They are all mirage-chasers, confident (despite ample evidence to the contrary) that the ultimate prize is within their grasp.

In the case of the colonists, that prize was mountains of diamonds or gold, or a quick passage to Asia. For historians, archaeologists and amateur sleuths, it is the equally elusive object or text that will reveal the Lost Colony’s fate. Yet in truth there is nothing very mysterious about the failure of the Roanoke settlement.

This bid to establish a European outpost off what is now the coast of North Carolina was doomed by ignorance of the basic facts of geography, geology and geopolitics. Conceived by Sir Walter Raleigh, a favoured courtier of Elizabeth I, as a means to “wrest the keys of the world from Spain”, the site was chosen “because on the mainland there is much gold”—and because Raleigh assumed it was strategically placed near an easy passage between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

None of these assumptions was grounded in reality. And reality quickly struck back, in the form of disease, starvation, hostile natives and even more hostile Spaniards. Hoping to obtain desperately needed supplies, John White, the governor, sailed for England. Delays caused by war, storms and other catastrophes meant it was three years before he was able to make it back. By then, the colony—which included his granddaughter, Virginia Dare, the first English child born in North America, according to legend—had vanished, leaving only a few tantalising clues behind.

Thus begins the second part of this saga: the fruitless search for answers—and the strange form of madness that seems to overcome anyone who gets too close to the subject. “The Lost Colony has a kind of inexorable pull, like a black hole,” a researcher tells Mr Lawler. But if the hunt itself is a matter of “chasing ghosts”, Mr Lawler is on firmer ground in his effort to explain its hold on the American imagination. Above all, the legend of the Lost Colony fulfils the need for an origin story, one that is all the more powerful for its pathos.

Still, it is an origin story of an exclusionary, even racist, cast. Given the devastation wrought on native populations, the obsessive focus on a handful of Anglo-Saxon settlers—including, most poignantly, the infant Virginia—is overblown. The notion that America began here, in the bogs and shifting sands of Roanoke Island, provides a distinctly Waspy pedigree for a nation with a far more complicated heritage.

Mr Lawler is an intrepid guide to this treacherous territory. When he attempts to track down one of the most controversial artefacts associated with the Lost Colony, he confesses: “No scholar in his right mind would risk his reputation on the Dare Stone, which by now was academically radioactive. Fortunately, I was no scholar.” This can-do spirit serves him well. His willingness to chase down every lead, no matter how outlandish, and his enthusiasm for the journey as much as the destination, make “The Secret Token” a lively and engaging read.

Publishers Weekly

Publishers Weekly

Part detective novel, part historical reckoning, Lawler’s engrossing book traces the story of—and the obsessive search for—the lost colony of Roanoke, the first English settlement in the New World, which disappeared without a trace in 1590, save for a “secret token” carved into a tree: “Croatoan.” Lawler (Why Did the Chicken Cross the World?), a contributing editor for Archaeologymagazine, provides detailed historical context about early North American colonization and brings to life the personalities behind the colony, including Walter Raleigh, its powerful backer, and Simão Fernandes, a Portuguese-born pilot often painted as the villain of the expedition. Digging in archives, visiting archeological excavations, and consulting previous leads, Lawler tries to wring a conclusion from the extant evidence: did the settlers die; did they merge with local Native American villages; did they leave the area? In the end, he decides it is more important to ponder why the story of Roanoke still resonates today, leading to a thoughtful and timely discourse about race and identity centered on Virginia Dare, the first English child born in the Americas, and since appropriated by both pro- and anti-immigrant voices. Without solving a long-standing (and likely unsolvable) historical mystery, Lawler makes a strong case for why historical myths matter.

Salon

Salon

“The Secret Token: Myth, Obsession, and the Search for the Lost Colony of Roanoke” is a very special kind of popular history. While most students of American colonial history are at least vaguely familiar with the mystery of Roanoke Island — the famous “lost colony,” the first permanent English settlement in the so-called New World that seemingly vanished into thin air — this new book by Andrew Lawler explores not only what might have happened to those colonists, but why their disappearance is shrouded in enigma for so many Americans.

In 1587, the colony of 115 people settled in what is now Hatteras Island, North Carolina, to form the very first outpost in what would eventually become the American colonies. Development of the colony seemed promising at first, but when colonial governor John White returned in 1590 on a resupply mission, he found that all of the inhabitants had vanished. The only clue as to what had happened to them was a “lost token” carved into a post on the fence around the village — the word “CROATOAN.” The letters “C-R-O” has also been carved into the wood of a tree.

Of course, the failure of the Roanoke Colony did not put an end to the British imperial project in North America, not by a long shot. By 1607, the colony of Jamestown in modern Virginia was founded and made to last, and less than 170 years after that (a blink of an eye in terms of human history), a collection of 13 much larger colonies would rebel against the Crown to form their own country, where this writer can be found in 2018 writing his review of “The Secret Token.”

Yet the legend of the Roanoke Colony has endured, a haunting reminder both of the perils of the early colonial days and a giant question mark at the center of America’s origin story. This is where Lawler’s book comes into the picture, diving headfirst into the latest developments regarding the fate of the colonists and providing colorful, affectionate portraits of the modern men and women who have been involved in cutting-edge forensic and archaeological investigations into the Lost Colony. Most importantly, though, Lawler sheds light on why the story of the Roanoke Colony remains so important today.

It wasn’t just the archaeology,” Lawler told Salon. “I went into it as a science writer following this mystery that archaeologists were going to solve. And in the course of that, I began to dig into the history of the Lost Colony itself and I asked a simple question: When did the term ‘Lost Colony’ come into use? And this is what led to what I think is an even more interesting aspect to this story than ‘solving the mystery,’ and that is that the ‘Lost Colony’ is a product of the 19th century. It was only in the 19th century that the Lost Colony was ‘lost.'”

As Lawler explained, there was a specific reason why Americans in the 19th century were so attracted to the story of the Roanoke Colony — namely, that it played into prevalent ideas about race.

“And the reason I discovered it was ‘lost’ was that the idea of the colonists assimilating with the Native Americans was a taboo,” Lawler told Salon. “Not only was it a taboo, the very idea was illegal, because at that point it was illegal [for] ‘colored’ — or non-whites, or blacks — to mix with one another.”

“So I realized there was something more interesting here than a mystery,” Lawler continued. “There was a way in which the ‘Lost Colony’ told us a lot about American anxieties about race, and also about immigration. Because the Lost Colony and Virginia Dare, who was the first English child born in America and born on Roanoke Island, they became legends in the 19th century.”

The 19th century, as Lawler points out, was a time when Andrew Jackson became a widely beloved populist president in large part by stoking fears of slave rebellions and Native American uprisings. It was also a time when new immigrants from places like Ireland, Italy and Eastern Europe poured onto America’s shores — immigrants who were not considered white by the Americans who already lived here. These fears about interracial mingling and foreign influence were at the root of the Roanoke Colony’s mystery, especially since one of the most likely explanations for its disappearance is that the colonists were absorbed into the nearby Native American tribes.

This history of racism was not far from Lawler’s mind when I spoke to him about his book; he pointed out how at least one popular anti-immigrant website (which has published work by white nationalists) directly references Virginia Dare.

“You can check out VDare.com, which is a website run by a man named Peter Brimelow, an English immigrant who has an anti-immigrant website, a website where he raises concerns about the influx of particularly African and South American peoples into the United States, basically ‘the brown peoples,'” Lawler told Salon. “So it’s very much alive. And this idea of white Americans being surrounded and endangered and encircled by ‘brown people’ is a very old idea, it’s not new, and the ‘Lost Colony’ is very much a way into that story.”

Lawler perhaps identified the political relevance of his book, and the Lost Colony’s story, most poignantly in a May editorial for the Washington Post:

Virginia Dare’s story reveals our desire to assimilate and our anxiety about doing just that. This conflict is at the root of the cultural battle that led to violence last summer in Charlottesville, as white Americans confront the growing numbers of black and brown people with whom they share a country. The infant of Roanoke offers us two very different futures. We can be martyred for some imagined race, or we can recognize that to be American is, in its essence, to be willing to redefine our beliefs, goals and even our ethnicity. Only by getting lost can we become something new.

Kirkus

Kirkus

Early settlers vanish, spawning centuries of speculation.

In 1587, more than 100 men, women, and children landed on Roanoke Island to become the first English settlers in the New World. In 1590, when the group’s leader returned from England with supplies, the settlement had disappeared, never to be found again. Lawler (Why Did the Chicken Cross the World?: The Epic Saga of the Bird that Powers Civilization, 2014, etc.), a contributing writer for Science and contributing editor for Archaeology, clearly has been infected with the “Lost Colony syndrome…an urgent and overwhelming need to resolve the question of what happened to the colonists.” He creates a vivid picture of the roiling, politically contentious, economically stressed Elizabethan world from which they sailed and a thorough—sometimes needlessly so—recounting of historical, archaeological, and weird theories to explain the disappearance. Besides visiting numerous archaeological digs, historical archives, and libraries in America, Portugal, and Britain and interviewing scores of experts, the author doggedly traces down frauds and hoaxes, no matter how improbable. The Zombie Research Society, he reports, warns of “something sinister still in the ground on Roanoke Island, waiting to be released into a modern population that is more advanced, more connected, but just as unprepared as ever.” Something sinister certainly emerged in the settlers’ relationship with Native Americans. At first, they “traded peacefully,” learned each other’s languages, and “formed mutually advantageous alliances.” But the English spread deadly disease among tribes with no immunities to Old-World pathogens, decimating communities, and although some leaders tried to treat Native Americans with gentleness, others lashed out against those they considered depraved savages. Native Americans responded with ruthless violence. Massacre is one theory of the settlers’ fate; another, equally possible, is assimilation. Most historians believe that the colonists, “if they survived, merged with indigenous society,” miscegenation that some found unpalatable. An 18th-century traveler, for example, “recoiled” from the idea that “white women found Indian husbands.”

In this enjoyable historical adventure, an unsolved mystery reveals violent political and economic rivalries and dire personal struggles.

American Archaeology Magazine

American Archaeology Review

In July 1587, ninety men, seventeen women, and eleven children sponsored by Sir Walter Raleigh and Queen Elizabeth landed on Roanoke Island in Pamlico Sound on the North Carolina coast. Their mission was to create the first English colony in the New World. Soon after landing, the governor’s daughter gave birth to the first English child born in America, Virginia Dare.

Because of hostile natives and lack of food and supplies, Governor John White returned to England that fall to resupply the colony. Due to various circumstances and the outbreak of war with Spain, White was unable to return for three years. When he finally reached the colony, it was deserted and the buildings dismantled. The word “Croatoan” was carved on the stockade and the letters C-R-O were carved on a nearby tree. But there was no carved cross, which was meant to signal that the colonists were under duress. White found no graves or other signs of foul play, and his search turned up nothing of interest.

Croatoan presumably referred to a friendly tribe on the Outer Banks, but a storm was approaching and White was unable to travel there. No confirmed trace of the “Lost Colony” has ever been found, even though a lot of people have been looking for some 400 years. This volume details the many attempts to answer, often with a touch of humor and irony, the question of what became of the colony by archaeologists, historians, hoaxers, actors, priests, Native Americans, and others.

The author, Andrew Lawler, is a free-lance science writer who has more than thousand newspaper and magazine articles (including in American Archaeology) to his credit. He chases clues from the Mid-Atlantic to London and encounters a cast of characters worthy of a great novel, including serious scholars and cranks. He visits archives and archaeological digs to get first hand impressions from the experts. Everyone has a theory of what happened to the Lost Colony, but no smoking gun of evidence is forthcoming. This is also the story of Virginia Dare, the first English child born in the New World. Lawler documents how her compelling story drives the search for the Lost Colony, how she became a symbol for feminine innocence and white Americans subjected to the cruelty of people of color.

The Secret Token is a highly readable story of myth and history, science and fraud, and of mystery and adventure. It is a book that is hard to put down. The mystery of the Lost Colony may never be solved, but it is intriguing to explore.

The North Carolina Historical Review

Chapter 16

Chapter 16

-Emily Choate

In The Secret Token: Myth, Obsession, and The Search for the Lost Colony of Roanoke, Andrew Lawler ironically makes a decent case against getting too curious about the first English settlement in North America. Get too close to the puzzling details of Roanoke — a vanished community, a handful of contradictory clues, a cast of eccentric characters making inexplicable decisions — and you might just find yourself sucked into an enigma with no end.

Lawler creates a vibrant portrait of the historical events surrounding the establishment of the Roanoke colony in the Outer Banks region of North Carolina and the colony’s subsequent disappearance. He also illuminates the “gravitational attraction” of this mystery for generations of historians, archaeologists, genealogists, and conspiracists. After more than four centuries, the search for answers about the fate of the vanished settlers continues to lure fresh recruits.

From the start, Lawler presents the story of Roanoke as a “haunting as much as a history.” “To die is tragic,” Lawler writes in his introduction, “but to go missing is to become a legend, a mystery.” Lawler argues that the “delicious dread” Roanoke provokes in us feeds the part of our story-loving psyches that are drawn to unresolved destinies.

As an extension of that fascination, Lawler also positions Roanoke as a potent, emblematic national myth. One purpose of his investigation is to reveal the legacy of the story, not just the events. Such national myths, he writes, “help us get our bearings in each age.” The Roanoke story acts as a touchstone for the cultural landscape surrounding it in any given era.

In the book’s first section, Lawler provides detailed context for the motives and hopes that likely drove 115 middle-class Elizabethan Londoners to brave huge unknowns in order to reach the New World, which at the time was dominated by Spanish colonizers, not English ones. Immune to romanticism about the European explorers, Lawler recounts the series of disastrous blunders the earliest English settlers made toward the Native American communities whose lives they disrupted or destroyed. His descriptions of this 16th-century world are seamless and atmospheric.

Part Two of The Secret Token focuses on the search for the lost colonists and features an array of figures who are—like the Roanoke mystery itself—vexing and fascinating. For example, the late-19th-century North Carolina politician Hamilton McMillan used the rumor of the Roanoke settlers’ white lineage blended into the local Lumbee tribe as pretext to offer the Lumbee concessions that raised their status above African Americans, thereby securing the tribe’s vote. But McMillan didn’t stop with political maneuvering; the legend hooked him, and he set out to research the truth for himself.

Modern-day Roanoke researchers include engaging figures like the British archaeologist Mark Horton, a scruffy “human Google” determined to discover from evidence in the marshy landscape whether or not the colonists fled to live with the nearby Croatoan tribe.

Acknowledging the evolving place of Roanoke in the larger picture of our world, Lawler concedes that “on a planet with a surfeit of missing people and forgotten refugees, this search feels at best quixotic and at worst perverse.” But stories like McMillan’s underscore the darker elements of racial turmoil that are interwoven through our history, stretching all the way back to those first settlers. Tracking this national origin myth through centuries inevitably raises stark questions about where we stand now.

Like America itself, Roanoke’s myth is by turns grand and maddening, full of loose ends and red herrings. Through lively prose, Lawler succeeds in making this story as irresistible as it is emblematic of our nation’s complex history.

The Asheville Citizen Times

The Asheville Citizen Times

—Patricia Furnish

Read on CitizenTimes.com

In search of the Lost Colony

Since elementary school, children from North Carolina and the surrounding area have learned about one of the founding mysteries of the state: what happened to the Lost Colony?

In his book “The Secret Token: Myth, Obsession, and the Search for the Lost Colony of Roanoke,” Andrew Lawler writes engagingly, and with a sense of humor, about how this mystery can overtake you.

Even the straightforward narrative of how the English tried to establish a colony off the coast of North Carolina in 1587 is layered in misdirection and falsehoods. Yes, the new arrivals consisted of 115 men, women and children who landed on Roanoke Island to create the first English settlement in the “New World.” But how they landed and what followed is unclear.

When the colony’s leader, John White, left for provisions and returned after a three-year delay, the settlers had vanished from the site. The only piece of evidence was a “secret token” carved into a tree. That agreed-upon sign and a lot of other clues are hotly debated in their meaning.

Lawler’s research did not take him where he thought it would. At a key point, he realized, “This story will not be so easily solved.” Archaeological work has not even found the actual location of the town now known as “The Lost Colony.”

According to Lawler, he had “bumped up against what we know from hard science.” He, then, decided to find out what the amateur investigators and history buffs were doing.

Archeologists have been digging in and around the location thought to be where the colony was established, but that has led to many false starts and a few misleading discoveries. It’s frustrating to professionals and amateurs who think this mystery can be solved. The investigations continue to this day.

For me, as a student of history, this is where Lawler’s book capably straddles the two overlapping worlds of experts and amateurs. What better subject than the Lost Colony, where people feel passionately about conspiracy theories, hoaxes, and verifiable facts?

“The Secret Token” also delves into how the Lost Colony became known as “lost” in the first place and when the obsession with finding out what happened began. The answers are surprising.

Lawler has discovered a larger historical truth: The Lost Colony tells us about ourselves as a nation. The enigma of what happened to the English settlers reveals our nation’s own intermingled early history, which includes Native Americans, Africans, and Europeans. We have what Lawler described as “an anxiety about assimilation” and the idea of America’s Manifest Destiny.

While it doesn’t fit the definition of true crime, Lawler rightly calls the mystery of the Lost Colony “America’s first cold case

Greensboro News and Record

Greensboro News and Record

–Linda C. Brinson

Virginia has Jamestown, Massachusetts has Plymouth, but the failed English colony on Roanoke Island in North Carolina has the most enduring place in the imagination of the nation that arose from these early settlements.

North Carolinians, reared on tales of The Lost Colony and Virginia Dare, taken as schoolchildren to see the outdoor drama at Manteo, may think we know all there is to know about this story.

But in his new book, “The Secret Token,” Andrew Lawler, an award-winning journalist and author, sheds new light on the colony and — equally fascinating — on the myths that have grown up around the mystery and their importance in the national story that Americans tell ourselves.

We know the basic facts: The colony that was supposed to have been the first permanent English settlement in the New World was established in 1587, organized by Sir Walter Raleigh, a knight who had a favored place in the court of Queen Elizabeth I. John White, a middle-age English merchant who was a keen observer and good artist, was the governor. Not long after the 115 colonists arrived on Roanoke Island, White’s daughter, Eleanor Dare, gave birth to the first English child born in America, a daughter named Virginia in honor of the queen. Late in 1587, White returned to England to get supplies for the fledgling colony, but various complications, most notably the war with Spain, prevented him from returning for three years, until the summer of 1590.

When White did return, he found that the colonists had vanished, leaving the three letters “CRO” carved into a tree, and the word Croatoan carved into a fencepost. That word is the “secret token” of Lawler’s title. According to White’s account, he and the colonists had agreed that if they left the island, they would leave behind the name of the place they went. If their departure was an emergency, they were to carve a cross over the name.

There was no cross, and there was also no other clue as to where the colonists had gone. There are many more questions than answers, giving rise over the next 400 years to all sorts of theories, speculations and claims.

Lawler grew up not in North Carolina but just over the Virginia line in Norfolk, and his family’s summers on the Outer Banks included treks to see “The Lost Colony” drama. He grew up to be a freelance journalist who writes for such publications as Science, Archaeology, National Geographic and Smithsonian.

In the book’s introduction, he tells how, despite warnings, he was drawn into the “black hole” of obsession about the fate of the vanished colony.

Fortunately for readers, Lawler’s obsession led him into extensive research on both sides of the Atlantic. He learned a great deal about the politics and ambitions that led to the attempted colony, the explorations that preceded it and what can be known about the personalities involved. North Carolinians may find themselves wishing that our state capital were not named in honor of Walter Raleigh, and those who have seen the outdoor drama may revise their opinion of the supposed villain, Fernandes, the Portuguese-born ship’s pilot.

What Lawler tells us about the origins and context of the attempted colony, as well as about Manteo, Wanchese and other Native Americans who were involved, is an engrossing story.

That’s only the beginning, however. The story gets livelier as he recounts various theories and claims over the years about the fate of the colonists, some fraudulent, others downright wacky, and even the more scientific ones speculative and incomplete. He talks about the Dare Stones, the Lumbee Indians, searches on Hatteras Island, the recent announcements about evidence that some of the colonists might have taken refuge in Bertie County, among other things.

Lawler’s investigations led him to wonder about the nature of the obsession he now shares. Because so little is known, he says, the Lost Colony gave Americans a legend and a story in which they could fill in the blanks as they see fit.

He relates how this story of failure was transformed over the years into an enduring mystery and a romantic story, how Virginia Dare was made into a symbol and something of a saint, and how she’s been used by various causes including the white supremacist movement.

He makes a good case that the story and the ways in which it has been spun, have much to do with the historic and continuing struggles in this country to deal with our complex racial heritage and identity.

Does Lawler solve the mystery of the Lost Colony? He has his theories.

He may have learned more, though, and helped readers to learn more, about why this enigma has such a lasting and compelling place in our national consciousness.

Library Hub

Library Hub

–Molly Odintz, Crime Reads Associate Editor

I’ve been on a true crime kick this week, immersing myself in my favorite childhood mystery: the lost colony of Roanoke. I spent many hours (or, you know, minutes) contemplating the the mystery of the word Croatoan as a child, but have only intermittently thought of the lost colonists since. As a rabid fan of American Horror Story, I adored Ryan Murphy’s take on the denizens of Roanoke, and I enjoyed the Roanoke chapter in Dixie Be Damned: 300 Years of Insurrection in the American South, which posits that the colonists of Roanoke formed a swampy socialist utopia with the Lumbee tribe of North Carolina. Yet not since childhood have I dived into the Roanoke mystery as thoroughly as I have over the past week, as I’ve been reading The Secret Token: Myth, Obsession, and the Search for the Lost Colony of Roanoke, by Andrew Lawler. Does Lawler solve the mystery? You’ll have to read the book (and I’ll have to finish reading the book) to find that out.

Open Letters Review

Open Letters Review

– Steve Donoghue

The sheer unlikeliness of Andrew Lawler’s previous book, Why Did the Chicken Cross the World? The Epic Saga of the Bird That Powers Civilization, threw into sharp relief the author’s writing ability; he carried the whole thing off so smartly and engagingly that he made a book about chickens a wholesale success. In light of the fact that Lawler has been freelancing newspaper and magazine articles for many, many venues for a long time, this is probably not surprising; he’s long since learned how to turn any subject into an interesting reading experience. Readers who missed all those articles and only discovered Lawler through Why Did the Chicken Cross the World might naturally have wondered what amazing things this author could do if he turned his skills to a subject with a bit more inherent dramatic potential than the international poultry industry.

Lawler’s newest is just such a book. The Secret Token: Myth, Obsession, and the Search for the Lost Colony of Roanoke focuses not just on the very sturdy evergreen mystery the lost colony of Roanoke (which, as he points out, historians and archeologists have for years been patiently pointing out was not actually “lost”) but also on the origin and growth of the legend itself.

The story was once a familiar part of any elementary-school American history education: in 1587, an English expedition of 115 men, women, and children arrived at Roanoke Island off the North Carolina coast with the intention of establishing the first English colony in the New World. But when a re-supply mission reached the colony three years later, they found it deserted – even the houses and barricades were gone. The only clue was the “secret token” of Lawler’s title, carved into a tree at the settlement site. Nearly a century later, when a beaver trader made his way to the island, a native calling himself “the emperor of Roanoke” offered to show the man “the ruins of Sir Walter Raleigh’s fort.”

The New World expedition had been the darling project of Raleigh, who features prominently in Lawler’s book. Indeed, The Secret Token is even stronger in its extensive sections back in Elizabethan England than it is on the shores of the Chesapeake; readers are taken on a fascinating, readable inquiry into the allure – not just financial but also imaginative – that the New World had the merchants, privateers, speculators, and ordinary citizens of the Old. All this careful grounding and broadening makes Lawler’s the best account of Roanoke to appear in many years.

“Geography colluded with the final passing of the Roanoke generation to consign the fate of the vanished settlers to oblivion – at least among Europeans,” Lawler writes. “Sailors steered clear of the treacherous shoals of the Outer Banks, considered the most dangerous waters south of Nova Scotia.” Likewise the “mystery” of the disappearance of the Roanoke colony was accidentally deepened by the prevailing cultural attitudes that prevailed for centuries after the event – cultural attitudes that avoided the obvious solution to the mystery: that the colonists, faced with fierce weather, grudging soil, and the threat of disease and starvation, willingly assimilated themselves into Native populations near and far – no mysterious disappearance, just a failed colony desperate to scatter and survive.

Of course The Secret Token won’t stop or even stall the outlandish speculation about Roanoke’s fate (space aliens have, inevitably, been dragged into the whole thing many times), but readers who prefer the facts need look no further.

Alternet

Alternet

–Matthew Rozsa

Read on alternet.org

“The Secret Token: Myth, Obsession, and the Search for the Lost Colony of Roanoke” is a very special kind of popular history. While most students of American colonial history are at least vaguely familiar with the mystery of Roanoke Island — the famous “lost colony,” the first permanent English settlement in the so-called New World that seemingly vanished into thin air — this new book by Andrew Lawler explores not only what might have happened to those colonists, but why their disappearance is shrouded in enigma for so many Americans.

In 1587, the colony of 115 people settled in what is now Hatteras Island, North Carolina, to form the very first outpost in what would eventually become the American colonies. Development of the colony seemed promising at first, but when colonial governor John White returned in 1590 on a resupply mission, he found that all of the inhabitants had vanished. The only clue as to what had happened to them was a “lost token” carved into a post on the fence around the village — the word “CROATOAN.” The letters “C-R-O” has also been carved into the wood of a tree.

Of course, the failure of the Roanoke Colony did not put an end to the British imperial project in North America, not by a long shot. By 1607, the colony of Jamestown in modern Virginia was founded and made to last, and less than 170 years after that (a blink of an eye in terms of human history), a collection of 13 much larger colonies would rebel against the Crown to form their own country, where this writer can be found in 2018 writing his review of “The Secret Token.”

Yet the legend of the Roanoke Colony has endured, a haunting reminder both of the perils of the early colonial days and a giant question mark at the center of America’s origin story. This is where Lawler’s book comes into the picture, diving headfirst into the latest developments regarding the fate of the colonists and providing colorful, affectionate portraits of the modern men and women who have been involved in cutting-edge forensic and archaeological investigations into the Lost Colony. Most importantly, though, Lawler sheds light on why the story of the Roanoke Colony remains so important today.

“It wasn’t just the archaeology,” Lawler told Salon. “I went into it as a science writer following this mystery that archaeologists were going to solve. And in the course of that, I began to dig into the history of the Lost Colony itself and I asked a simple question: When did the term ‘Lost Colony’ come into use? And this is what led to what I think is an even more interesting aspect to this story than ‘solving the mystery,’ and that is that the ‘Lost Colony’ is a product of the 19th century. It was only in the 19th century that the Lost Colony was ‘lost.’”

As Lawler explained, there was a specific reason why Americans in the 19th century were so attracted to the story of the Roanoke Colony — namely, that it played into prevalent ideas about race.

“And the reason I discovered it was ‘lost’ was that the idea of the colonists assimilating with the Native Americans was a taboo,” Lawler told Salon. “Not only was it a taboo, the very idea was illegal, because at that point it was illegal [for] ‘colored’ — or non-whites, or blacks — to mix with one another.”

“So I realized there was something more interesting here than a mystery,” Lawler continued. “There was a way in which the ‘Lost Colony’ told us a lot about American anxieties about race, and also about immigration. Because the Lost Colony and Virginia Dare, who was the first English child born in America and born on Roanoke Island, they became legends in the 19th century.”

Yet the legend of the Roanoke Colony has endured, a haunting reminder both of the perils of the early colonial days and a giant question mark at the center of America’s origin story. This is where Lawler’s book comes into the picture, diving headfirst into the latest developments regarding the fate of the colonists and providing colorful, affectionate portraits of the modern men and women who have been involved in cutting-edge forensic and archaeological investigations into the Lost Colony. Most importantly, though, Lawler sheds light on why the story of the Roanoke Colony remains so important today.

“It wasn’t just the archaeology,” Lawler told Salon. “I went into it as a science writer following this mystery that archaeologists were going to solve. And in the course of that, I began to dig into the history of the Lost Colony itself and I asked a simple question: When did the term ‘Lost Colony’ come into use? And this is what led to what I think is an even more interesting aspect to this story than ‘solving the mystery,’ and that is that the ‘Lost Colony’ is a product of the 19th century. It was only in the 19th century that the Lost Colony was ‘lost.’”

As Lawler explained, there was a specific reason why Americans in the 19th century were so attracted to the story of the Roanoke Colony — namely, that it played into prevalent ideas about race.

“And the reason I discovered it was ‘lost’ was that the idea of the colonists assimilating with the Native Americans was a taboo,” Lawler told Salon. “Not only was it a taboo, the very idea was illegal, because at that point it was illegal [for] ‘colored’ — or non-whites, or blacks — to mix with one another.”

“So I realized there was something more interesting here than a mystery,” Lawler continued. “There was a way in which the ‘Lost Colony’ told us a lot about American anxieties about race, and also about immigration. Because the Lost Colony and Virginia Dare, who was the first English child born in America and born on Roanoke Island, they became legends in the 19th century.”

Virginia Dare’s story reveals our desire to assimilate and our anxiety about doing just that. This conflict is at the root of the cultural battle that led to violence last summer in Charlottesville, as white Americans confront the growing numbers of black and brown people with whom they share a country. The infant of Roanoke offers us two very different futures. We can be martyred for some imagined race, or we can recognize that to be American is, in its essence, to be willing to redefine our beliefs, goals and even our ethnicity. Only by getting lost can we become something new.

Bookmarks

Coastal Review Online

Coastal Review Online

–Kip Tabb

MANTEO – The question of what happened to the 115 men, women and children of the Lost Colony of Roanoke Island has endured in the American psyche for generations.

Established in 1587 and soon abandoned in a land of warring Native American tribes, short on supplies and lacking the skills needed to survive, the mystery of their fate has been unsolved since John White found the word “Croatoan” carved into a tree in 1590.

Using his perspective as a journalist and science writer, Andrew Lawler weaves a compelling and remarkable tale in “The Secret Token: Myth, Obsession and the Search for the Lost Colony of Roanoke.” Lawler is also the author of “Why Did the Chicken Cross the World? The Epic Saga of the Bird that Powers Civilization,” the story of how a semi-flightless Asian bird spread across the globe and become a source of food and power. As a journalist, his byline has appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, National Geographic, Smithsonian and others. He is a contributing writer for Science and contributing editor for Archaeology.

Lawler’s research bringing “The Secret Token” to life is astonishing, traipsing back and forth across the Atlantic to research original sources. Interviewing researchers, archaeologists, historians and the occasional quixotic theorists in his quest to discover what truly happened, he guides the reader on a journey of discovery, and he is a wide-eyed guide, as astonished at what he discovers as his tour group.

“I thought I knew the story when this all began,” he said.

The writing reflects Lawler’s journalism background. The sense of wonder comes in the sheer volume of information; the style though is objective and fact-based, and if there are conclusions to be drawn, it is because of the details that are presented in the book and not because of any opinion that he ventures.

Because he avoids expressing an opinion, as the facts build, “The Secret Token” seems, at times, like a mystery novel constructing a compelling case. Yet there is no smoking gun in this instance, saying “This is what happened.” What there is, rather, is the tapestry of the American experience as it has evolved over 400 years.

The search for the lost colonists becomes a reflection of the evolution of American thought.

“It was lost by us only in the 19th century,” he said, pointing to the first comprehensive history of this country, George Bancroft’s “A History of the United States.” The first three volumes of his 10-volume set were published in 1834 and covered the time from the first attempt at colonizing America to the Revolution.

Although Harvard-trained Bancroft had spent considerable time in Europe, especially Germany, at a time of rising romanticism in thought and a belief in myth to define an emerging German society.

“He cast it in those Gothic terms,” Lawler said

Seeped in the romantic writings of Europe, Bancroft wove a tale that fit the narrative.

“He called Virginia Dare the first English child born in the New World. He made her into a national symbol,” Lawler said.

That romanticized 19th century view of a white babe born among the “savages” still lingers. It can be seen even today in Paul Green’s “The Lost Colony,” the outdoor drama performed, in theory, upon the very land of the Lost Colony.

The play ends with the weakened yet determined colonists walking off into the wilderness, her father Anais dead at the hands of the savages, her mother holding the babe in her hands.

Green, though, was a radical in his day. During a period in U.S. history when miscegenation was illegal, especially in the South, his English settler Old Tom and native Agona marry, foretelling, perhaps what many archaeologists and historians feel eventually did happen.

“He (Green) supposed an assimilation there, with Old Tom and Agona marrying,” Lawler said.

Lawler does not just look at the influence of the Lost Colony on American thought, he also examines in detail the events that were occurring in Europe at the time.

What emerges is a place of political machination and intrigue. Spain, the dominant power of its time, pitted against England, an impoverished backwater land suspicious of science and innovation.

The detail is extraordinary but important in carrying the story forward.

In Green’s play the colonists are terrified of the Spanish. History demonstrates they were justified in their fear. On more than one occasion, all the inhabitants of a non-Spanish colony were put to the sword, and Roanoke Island was well within land Spain claimed.

The power struggle for control of the Americas and the seas played out in those 115 colonists. The colonists were seeking opportunity — a chance to better themselves economically and socially.

Whatever the game Raleigh, Queen Elizabeth and Simao Fernandes may have been playing is not as clear.

Fernandes, the pilot who insisted the colonists be deposited on Roanoke Island even though plans called for them to begin their life in the Chesapeake area, has always been suspect. But in Lawler’s nuanced examination of the man and the times his motivation does not seem nearly as sinister.

The modern characters who comprise the search for the Lost Colony may be the most fascinating. A remarkable conglomerate of scientists, quasi-scientists and crackpots fill the pages.

Lawler’s eye for detail in describing them is wonderful.

There is British archaeologist Mark Horton, who “… to the dismay of his dig team, refuses to wear a belt around his perpetually sagging trousers.” Nor does the man bathe as often as the people he is working with would wish.

Fred Willard, who lived on the Outer Banks, was convinced the Dare Stone, a rock brought to light in the 1930s that seemed to tell the story of Virginia Dare’s demise, was real. He led his own excavations trying to find proof. “His bald pate, scraggly beard and piercing eyes gave him the look of a vengeful marsh prophet,” Lawler writes in describing him.

But the physical descriptions are the frame of a picture, a way to introduce the personalities. What emerges from Lawler’s interviews and observations are nuanced and complex characters who believe the quest for the truth will have an ending.

“The Secret Token” is a great read. It does not give a definitive answer to what happened to the Lost Colony. And in reading the book, the thought that there may not be a definitive answer seems likely. Yet what Lawler has done is expand the search for the inexplicable and unknowable into an examination of how we think of ourselves and our history.

Richmond Times-Dispatch

Richmond Times-Dispatch

–Drew Gallagher

If you are headed to the Outer Banks this summer, pick up a copy of Andrew Lawler’s “The Secret Token: Myth, Obsession, and the Search for the Lost Colony of Roanoke.”

And it’s probably not a bad idea to pick up a shovel and metal detector while you’re at it, because after you finish Lawler’s book, you’ll have some notion that you are now prepared to solve the single greatest mystery in American history.

That is what happened to the English settlers who were left on Roanoke Island in North Carolina to establish the first colony in North America in 1587. Circumstances forced the colony’s governor, John White, to sail back to England and abandon his colonists and settlement, but with the vow that he would return in a few months with much-needed supplies and more colonists.

For myriad reasons, the desperate White was unable to return to Roanoke Island until 1590, and when he finally did, there was no living trace of the colonists.

White discovered two messages (the “Secret Token”) carved into wood at the abandoned colony that indicated the colonists had moved 50 miles south to Croatoan Island (now Hatteras Island).

But when White tried to sail the following day, fate intervened again. He was never able to reach the island and confirm their existence or story. His ship returned to England, and White was never able to return to the New World. His colony was “lost” to both White and to history.

The mystery of the Lost Colony has hounded scholars and sleuths for centuries, and Lawler delves deep into the pages of history and follows some threads and rumors all the way to Spain and Portugal in search of sailors’ logs and clues tucked away in musty old libraries.

He also joins a number of current excavations in North Carolina as assorted parties attempt to locate the Lost Colony over 400 years later. Spoiler alert: They have yet to find it.

There are many theories as to what became of the colonists. The one that is most pervasive skews similar to the plot of the play “The Lost Colony” that is produced every summer in Manteo mostly because every visitor to the Outer Banks has seen the play at some point in their visits.

Lawler sifts through these theories at length. What emerges is a brilliant work of scholarship that may not explain the fate of the colonists, but it certainly gives plenty of fodder for the next generation of amateur history sleuths.

Outer Banks Common Good

Outer Banks Common Good

–Kip Tabb

Read on obxcommongood.org

Andrew Lawler is a master storyteller. The author of The Secret Token-Myth, Obsession and the Search for the Lost Colony visited the Outer Banks to talk about his book—just released last month—and what the search for the 115 colonists has meant to him.

The Bryan Cultural Series was host to two events this past weekend featuring Lawler. On Friday evening he was at All Saints Episcopal Church in Southern Shores and he appeared Sunday afternoon with ECU archaeologist Charles Ewen at the Dare County Arts Council Gallery in Manteo.

Lawler began his talk in Southern Shores by telling the audience that at one time he thought he knew the story of the Lost Colony.

“Growing up in Norfolk, Virginia, (visiting the Outer Banks) was the thing we would do every summer. There were two things to do. Bingo and cross the bridge to Roanoke Island and sit on the park benches for three and a half hours. I did that every year from when I was three until I was 18. So I thought I knew everything there was to know about it,” he said.

A science writer whose articles have appeared in the New York Times and National Geographic, Lawler was in England working on a story and a chance encounter began his obsession.

“One evening on a rainy night in Oxford or Cambridge I was seated by an English archaeologist and I asked him where he was digging,” Lawler said. “And he said, ‘Zanzibar.’”

Curious, Lawler asked if there were any digs in the United States.

“Oh there’s a place but you’ve never heard of it. It’s called Hatteras” his British archaeologist said.

“And I said ‘Hatteras Island.’”

“Why yes.”

“And I asked, ‘Have you found the lost Colony?’ And he said, ‘As a matter of fact we did.’”

The archaeologist was Mark Horton who with Hatteras naive Scott Dawson has been digging at Buxton since 2009.

In The Secret Token, Horton portrays the artifacts that have been found at Buxton as conclusive.

Other archaeologists are not so sure.

When ECU Charles Ewen joined Lawler for a discussion of The Secret Token and what the various artifacts mean, he began by noting that our entire body of historic documentation for the Lost Colony consists of the writings of John White.

“Since there is so little factual evidence I always have to say, ‘How much of what John White actually wrote is all the truth?’” he asked. “There are two camps. One of them has a bumper sticker that says, ‘John White said it. I believe it. That settles it.’ And then there’s the more skeptical.”

Ewen is clearly in the skeptical camp.

He pointed out that although there is suggestive evidence at the Hatteras dig, none of it is conclusive and all of it can be explained in equally as convincing ways that would not include the Lost Colonists.

In his book, Lawler discusses at some length those very issues, and it is that full range of discussion that makes The Secret Token such a absorbing book.

The book is rich in detail, filled with facts that trace the historic and political forces at work that created the Lost Colony in the 1580s.

In the world Lawler uncovers, England is a backward nation lacking trained navigators, scientists and resources to colonize the New World. He explains how Sir Walther Raleigh, very much in Queen Elizabeth’s favor, was granted the right to license all liquor establishments in England and that revenue is how he financed a venture the government did not have the money to undertake.

The world the Colonists enter in 1587 is far more complex than they realize with Indian tribes and kingdoms forming alliances and seeking political advantage with a lust for power that was remarkably similar to Europe.

What Lawler has done—and it is what makes The Secret Token so compelling—is examine what the disappearance of the 115 colonist has come to mean.

It wasn’t until the 1830s that most people in America realized there was a Lost Colony—and that came about because of Harvard trained historian George Bancroft’s A History of the United States.

Heavily influenced by the romantic philosophies that were sweeping across Europe at the time, he cast the birth of Virginia Dare as an innocent child born in a world of savages.

Before that time, if it was contemplated at all, the Roanoke colony was thought of as a failed attempt. But when Bancroft recast its fate, Virginia Dare became an icon of the struggle to tame the United States and create a world in which an innocent white child would be safe.

“He made her into a national symbol,” Lawler said.

That symbolism continues until this day.

Paul Green was radical for his time. During a period when miscegenation was illegal—even a felony in some states—he has Old Tom, the comic relief, marrying the Native woman Agona. And it is Old Tom who, with Agona asleep at his feet as he stands guard, talks about personal redemption and his hope for the future.

But in the end, the weak but determined colonists, walk off into the wilderness, Virginia Dare in her mother’s arms and her father dead at the hands of Wanchese and his tribe of savages.

If that is the myth, the reality, however, is something we still don’t know, and Lawler explores in wonderful detail the archaeologists, historians and occasional crackpot that have spent their lives in search of the answer to the Lost Colony.

The book is a fantastic read, very well written with an amazing amount of research. It is detailed, with each fact carefully layered upon other facts so that the entire fantastic story of the 115 men, women and children who sailed from England hoping to discover a new life for themselves, becomes the story of who we are as a nation and a people.

“What I discovered, is this is really the American creation story. This is the story about how we became who we are. It’s where our national DNA formed,” Lawler said.

Next on the schedule for the Bryan Cultural Series is the 4th Annual Surf and Sounds Chamber Music Series. These free concerts are scheduled from Tuesday August 21 through Friday August 24 at sites scattered from Duck to Buxton. The concerts feature a group of talented professional musicians offering exceptional performances. For more information about the concerts visit bryanculturalseries.org

The Bryan Cultural Series is a non-profit organization formed in 2012. The board of directors is composed of nine community leaders dedicated to offering a series of high quality cultural events. These events will include a variety of visual, literary and performing arts. The board strives to glean from talent that has attained regional as well as national recognition to maintain a high standard.

Substantial support for this annual cultural offering of events is provided by Towne Bank, Village Realty, Ramada Plaza Hotel of Kill Devil Hills and Hilton Garden Inn of Kitty Hawk. For more information about this events and future programs, visit bryanculturalseries.org.

The Intelligencer

The Intelligencer

–Gregory S. Schneider

Read on theintelligencer.com

The lost colony of Roanoke Island will always be one of the weirdest episodes in American history. It has managed to stay in the news, off and on, for 431 years: the case of 100-plus English settlers vanishing in the woods and marshes of coastal North Carolina. But most Americans who know the basic mystery have no idea of the deep, tantalizing layers of strangeness that underlie almost every aspect of the tale.

Things were off-kilter from the beginning. Sir Walter Raleigh had bankrolled a settlement for the shores of the Chesapeake Bay. But when the ship containing some 115 settlers arrived in the New World in July 1587, the captain and pilot mysteriously dumped them at Roanoke Island instead. Tucked behind today’s Outer Banks, the island was reachable through some of the most dangerous waters of the East Coast. The native inhabitants had already been insulted and mistreated by other Englishmen, so this wasn’t the most welcoming location.

The man Raleigh chose to lead the colony, John White, was an artist, not an explorer. He brought his pregnant daughter and her husband. A few weeks after landing, daughter Eleanor gave birth to the first English baby born in America, Virginia Dare. At which point White – who was supposed to be running things – sailed all the way back to England to ask for more supplies.

He didn’t return for three years. By then, the settlers were gone. There were intriguing clues to their whereabouts carved on a tree and a post, including the name of a nearby native village. But rather than check that out, White sailed again for England.

And the colony has been lost ever since.

It’s human nature to wonder what happened to those men, women and children. Capt. John Smith tried to figure it out after arriving at Jamestown in 1607. But it seems that every effort to solve the mystery has spun out strange tendrils of its own.

Andrew Lawler warns in his new book, “The Secret Token: Myth, Obsession, and the Search for the Lost Colony of Roanoke,” that Lost Colony fever is a kind of madness. Happily, that doesn’t stop him from plunging into the wild terrain of theories and conflicting evidence where so many others have disappeared. Lawler manages to do this in a clear-eyed way, conscious of whether he, too, is getting lost. He makes a good case that the search itself goes to the heart of what it means to be American. Plus, it’s just plain fascinating.

As a writer for Science magazine, National Geographic and Smithsonian, Lawler has a polished, pop-history writing style – informative without seeming dense, entertaining but not pandering.

One of the strengths of the first section of the book is its depiction of the civilizations that had already been clashing for generations when Raleigh sent out his settlers. Not only were the sophisticated nations of native peoples disrupted by European colonization, but the Spanish had explored and settled along the East Coast for decades before the English arrived. The city of St. Augustine, Fla., boasted 250 houses more than a century before any English colony could claim such a number.

One of Lawler’s most fascinating points – which he touches on too briefly – is that the English pirate Sir Francis Drake may have left a large group of formerly enslaved workers on the Carolina coast in the year before the Lost Colony. Drake had captured the Africans and native South Americans during a raid on the Spanish port of Cartagena. If he left them at Roanoke, as some accounts suggest, they would “form a mysterious (BEGIN ITAL)other(END ITAL) lost colony,” Lawler writes. “Their presence on Roanoke would mean that the bulk of the first permanent settlers of England’s initial New World colony were neither Christian nor European but North African Muslims as well as followers of West African and South American traditions.”

Lawler also does a good job conveying the strangeness of one of the central figures of the Lost Colony mystery: the wayward governor, John White. After describing White’s return to find the colony abandoned and no sign of his daughter or granddaughter, Lawler puts his finger on something that by now has been nagging at the reader. “The record White left behind has a hallucinatory quality unlike almost anything in early American literature,” Lawler writes. “Bonfires ignite as if by ghosts. There are footprints in the sands of a silent forest. … There is an otherworldly detachment to his tale, as if the governor were a disembodied witness rather than the main character in an emotionally wrenching journey.”

He’s right. White’s narrative seems like a surreal dream. It brings to mind another strange account of adventures: Edgar Allan Poe’s novel “The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket,” which reads as though written by someone who never traveled the seas and made it up as he went along. Possibly while taking laudanum.

So, what does it all mean? That’s part two of the book, where Lawler tries to mop up the historical mess with centuries of theories about what really happened. He roams from John Smith’s sighting of white children among the Indians, to the mid-20th-century craze for messages supposedly left on stones by Eleanor Dare, to the collection of misfits and competing scholars who toil away at the question today.

It’s frustrating stuff. Every idea that seems to have merit – complete with secret details discovered on ancient maps – either evaporates or remains unresolved. There have been intriguing recent developments, but we won’t spoil some of the book’s juicy tidbits.

Though he presents himself as a skeptical arbiter who will hold any charlatans accountable, Lawler falls into the habit of ending chapters with suggestive cliffhangers. It works, for a while, but gets distracting.

The third and final section of the book aims for a cultural reckoning with the legacy of the Lost Colony. The heavier tone – who knew that Virginia Dare was once a symbol for white supremacists? – is a bit of a comedown after the crazy fun of the conspiracy theories.

But the themes of mingled races, of cultures clashing to create something new, are surprisingly fresh and powerful. The issues raised by the Lost Colony are still playing out. It’s a mystery in which all Americans have a stake.

Napa Valley Register

Napa Valley Register

–Gregory S. Schneider

Read on napavalleyregister.com

The lost colony of Roanoke Island will always be one of the weirdest episodes in American history. It has managed to stay in the news, off and on, for 431 years: the case of 100-plus English settlers vanishing in the woods and marshes of coastal North Carolina. But most Americans who know the basic mystery have no idea of the deep, tantalizing layers of strangeness that underlie almost every aspect of the tale.

Things were off-kilter from the beginning. Sir Walter Raleigh had bankrolled a settlement for the shores of the Chesapeake Bay. But when the ship containing some 115 settlers arrived in the New World in July 1587, the captain and pilot mysteriously dumped them at Roanoke Island instead. Tucked behind today’s Outer Banks, the island was reachable through some of the most dangerous waters of the East Coast. The native inhabitants had already been insulted and mistreated by other Englishmen, so this wasn’t the most welcoming location.

The man Raleigh chose to lead the colony, John White, was an artist, not an explorer. He brought his pregnant daughter and her husband. A few weeks after landing, daughter Eleanor gave birth to the first English baby born in America, Virginia Dare. At which point White — who was supposed to be running things — sailed all the way back to England to ask for more supplies.

He didn’t return for three years. By then, the settlers were gone. There were intriguing clues to their whereabouts carved on a tree and a post, including the name of a nearby native village. But rather than check that out, White sailed again for England.

And the colony has been lost ever since.

It’s human nature to wonder what happened to those men, women and children. Capt. John Smith tried to figure it out after arriving at Jamestown in 1607. But it seems that every effort to solve the mystery has spun out strange tendrils of its own.

Andrew Lawler warns in his new book, “The Secret Token: Myth, Obsession, and the Search for the Lost Colony of Roanoke,” that Lost Colony fever is a kind of madness. Happily, that doesn’t stop him from plunging into the wild terrain of theories and conflicting evidence where so many others have disappeared. Lawler manages to do this in a clear-eyed way, conscious of whether he, too, is getting lost. He makes a good case that the search itself goes to the heart of what it means to be American. Plus, it’s just plain fascinating.

As a writer for Science magazine, National Geographic and Smithsonian, Lawler has a polished, pop-history writing style — informative without seeming dense, entertaining but not pandering.

One of the strengths of the first section of the book is its depiction of the civilizations that had already been clashing for generations when Raleigh sent out his settlers. Not only were the sophisticated nations of native peoples disrupted by European colonization, but the Spanish had explored and settled along the East Coast for decades before the English arrived. The city of St. Augustine, Fla., boasted 250 houses more than a century before any English colony could claim such a number.

One of Lawler’s most fascinating points — which he touches on too briefly — is that the English pirate Sir Francis Drake may have left a large group of formerly enslaved workers on the Carolina coast in the year before the Lost Colony. Drake had captured the Africans and native South Americans during a raid on the Spanish port of Cartagena. If he left them at Roanoke, as some accounts suggest, they would “form a mysterious other lost colony,” Lawler writes. “Their presence on Roanoke would mean that the bulk of the first permanent settlers of England’s initial New World colony were neither Christian nor European but North African Muslims as well as followers of West African and South American traditions.”