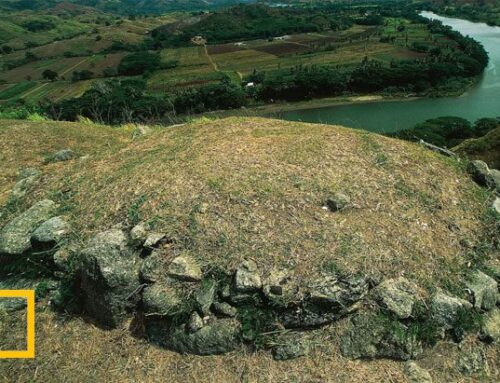

An aerial view of the archaeological excavation at Berkeley Plantation on the James River in Virginia.

PHOTOGRAPH BY MARK THIESSEN

An excavation provides tantalizing hints about a little-known group that celebrated Thanksgiving two years before the New England Pilgrims.

Berkeley Plantation, VA: The autumn sun was rapidly dropping toward the broad James River when two pieces of reddish baked clay, each not much larger than a thumbnail, emerged from the Virginia mud. Mark Horton, an archaeologist from the UK’s University of Bristol, gave the fragments a lick with his tongue and peered closely at tiny patterns incised into the objects. After a moment’s pause, he said, “We are looking for a needle in a haystack—I wonder if this is it!”

Horton’s needle is physical evidence from the site of the first English Thanksgiving in the New World—one that took place five hundred miles south of Plymouth Rock and nearly two years earlier. Here, just thirty miles upstream from Jamestown, a little-known group of religious-minded settlers celebrated with prayer their successful voyage from England in December 1619, and pledged to do so annually on the same date.

In just three years, however, the settlers’ community, known as Berkeley Hundred, came to a sudden and bloody end after a deadly attack by Native Americans, part of a larger uprising that nearly wiped out the entire Virginia colony. Eighteenth-century colonists subsequently built an elegant plantation house on the site that still looms over the James. Here, President William Henry Harrison was born and the melancholic tune Taps was first played by a Union soldier during the Civil War. But until now, no seventeenth-century artifacts have ever been found on the thousand-acre property that might point to the location of the original Berkeley Hundred settlement.

The challenge drew Horton, who has spent the last decade digging on the grounds of Berkeley Castle in Gloucestershire—the English estate which gave the Virginia effort its name—uncovering coins, pottery, and buildings from Roman to modern times. He enlisted collaborators from the University of Tennessee at Knoxville to conduct a first season of excavation at the Berkeley Plantation in October. “The landscape here is remarkably similar to Gloucestershire,” said Horton as the team dug a single trench in a field just a few dozen yards from the river. “The James is here as wide as the Severn—this was a landscape [the settlers] could understand.”

Thanksgiving Without the Turkey

Unlike most of their Virginia counterparts, who were focused exclusively on profiting from tobacco, the Berkeley expedition was a tight-knit group with a strong religious sensibility. They also were the first boatload of settlers from western England, and Horton hopes to find evidence of their distinctive way of life.

A remarkable cache of papers discovered in the late nineteenth century details plans for the colony, listing supplies down to the required 5.5 tons of beer and 127 pounds of bacon and horsemeat.

Among the requirements was an assembly house (a combination church and meeting hall) as well as 400 acres of common land to be set aside for grazing. The Berkeley settlers were also to gather together daily to eat and pray.

Archaeologists on a joint U.K.-U.S. excavation team conduct a ground-penetrating radar survey at Berkeley Plantation. PHOTOGRAPH BY REBECCA HALE

These signs of a communal sensibility were common to religious groups in England at the time, said James Horn, a historian and president of Jamestown Rediscovery, who is not involved in the Berkeley dig. “They are Anglicans, not Pilgrims, but they have a similar tenor.”

Three dozen male Berkeley settlers landed here on December 4, 1619. Their first order of business, according to their instructions, was to say the following prayer: “We ordain that this day of our ships arrival, at the place assigned for plantation, in the land of Virginia, shall be yearly and perpetually kept holy as a day of Thanksgiving to Almighty God.”

The men likely knelt on the cold ground by the shore. So far as can be known, there was no feast and no Native Americans were present. In fact, under Anglican tradition, they may have fasted rather than feasted.

That this celebration occurred two years before its more famous counterpart in New England has long rankled Virginians. When Massachusetts-born President John F. Kennedy issued a Thanksgiving proclamation in 1962 touting the Pilgrim’s establishment of the holiday, a Virginia senator complained. One of the president’s last acts before his assassination the following year was to acknowledge “over three centuries ago, our forefathers in Virginia and Massachusetts, far from home, in a lonely wilderness set aside a time of Thanksgiving.”

A broken clay pipe found during the excavation dates to the first half of the 1600s. Colonists arrived at Berkeley in December 1619.

PHOTOGRAPH BY REBECCA HALE

A Richmond newspaper crowed in a headline that “President Concedes: Virginia Receives Thanksgiving Credit.” (Historians point out, however, that there are several examples of Spanish feasts of thanksgiving prior to the arrival of the English in the New World.)

“Chaps! Let’s dig!”

In 1620, more settlers and supplies arrived at Berkeley Hundred from England. Two years later, English hunger for Indian land, driven by lucrative prices in London for Virginia-grown tobacco, prompted the local Powhatan to strike, killing a dozen people at Berkeley Hundred and some four hundred across the colony.

Berkeley was abandoned until later in the century and its original settlement location forgotten, says Malcolm Jamieson, the owner of Berkeley Plantation, who gave Horton permission to excavate. Before digging, the team chose a promising area on the working farm. “We are between two bluffs, near fresh water, and close to the river,” Horton explained, standing in a field just a few dozen yards from the shore. Using ground-penetrating radar and a magnetometer, the archaeologists located a disturbed chevron-shaped area that the excavators hoped might signal a buried structure.

“Chaps!” Horton called out to the team after examining the maps on a laptop. “The answer lies in the soil! Let’s dig!” Within hours, a small trench revealed a handful of Native American arrowheads, as well as native and colonial pottery.

Archaeologists sift soil from an excavation trench at Berkeley Plantation. Native American and European-style artifacts were found during the dig. PHOTOGRAPH BY REBECCA HALE

Two pieces of tobacco pipe found in the last hour of excavations prompted particular excitement. Preliminary analysis by the team suggests that the pipes, made from local material, date to between 1607—when the English arrived at Jamestown—and the mid seventeenth century. At least one closely resembles a 1610 pipe from Jamestown. “This would give us a nice clue that the colony was located on land already occupied and cleared by Native Americans,” said Horton, gesturing at a Ziploc bag of Indian pottery and arrowheads. The artifacts suggest an Indian settlement was here prior to the arrival of the English. He added that while the pipes are not a “smoking gun,” they hint at the European settlement’s location.

Horton’s team hopes to return for more extensive excavations in 2019, the four hundredth anniversary of the colony’s founding, as well as the first recorded English Thanksgiving in the New World. “We want to find a tangible link to this place and this period, about which we know so little,” he added.

Horn agrees that the effort could shed much needed light on a critical moment in American history. The same year that the initial Berkeley settlers arrived, the first Africans and large numbers of women landed at Jamestown; that summer, the first representative assembly in the New World gathered there as well. “This is a dramatic story that took place in a dramatic time,” Horn added. “A sustained dig here could be incredible.”