5,000 years ago, a long-buried society in the Iranian desert helped shape the first urban age

Even local archaeologists with the benefit of air conditioned cars and paved roads think twice about crossing eastern Iran’s rugged terrain. “It’s a tough place,” says Mehdi Mortazavi from the University of Sistan Baluchistan in the far eastern end of Iran, near the Afghan border. At the center of this region is the Dasht e Lut, Persian for the “Empty Desert.” This treacher ous landscape, 300 miles long and 200 miles wide, is covered with sinkholes, steep ravines, and sand dunes, some topping 1,000 feet. It also has the hottest average surface temperature of any place on Earth. The forbidding territory in and around this desert seems like the last place to seek clues to the emergence of the first cities and states 5,000 years ago.

Even local archaeologists with the benefit of air conditioned cars and paved roads think twice about crossing eastern Iran’s rugged terrain. “It’s a tough place,” says Mehdi Mortazavi from the University of Sistan Baluchistan in the far eastern end of Iran, near the Afghan border. At the center of this region is the Dasht e Lut, Persian for the “Empty Desert.” This treacher ous landscape, 300 miles long and 200 miles wide, is covered with sinkholes, steep ravines, and sand dunes, some topping 1,000 feet. It also has the hottest average surface temperature of any place on Earth. The forbidding territory in and around this desert seems like the last place to seek clues to the emergence of the first cities and states 5,000 years ago.

Yet archaeologists are finding an impressive array of ancient settle ments on the edges of the Dasht e Lut dating back to the period when urban civilization was emerging in Egypt, Iraq, and the Indus River Valley in Pakistan and India. In the 1960s and 1970s, they found the great centers of Shahr i Sokhta and Shahdad on the desert’s fringes and another,Tepe Yahya, far to the south. More recent surveys, excavations, and remote sensing work reveal that all of eastern Iran, from near the Persian Gulf in the south to the northern edge of the Iranian plateau, was peppered with hundreds and possibly thousands of small to large settlements. Detailed laboratory analyses of artifacts and human remains from these sites are providing an intimate look at the lives of an enterprising people who helped create the world’s first global trade network.

Far from living in a cultural backwater, eastern Iranians from this period built large cities with palaces, used one of the first writing sys tems, and created sophisticated metal, pottery, and textile industries. They also appear to have shared both administrative and religious ideas as they did business with distant lands. “They connected the great corridors between Mesopotamia and the east,” says Maurizio Tosi, a University of Bologna archaeologist who did pioneering work at Shahr i Sokhta.“They were the world in between.”

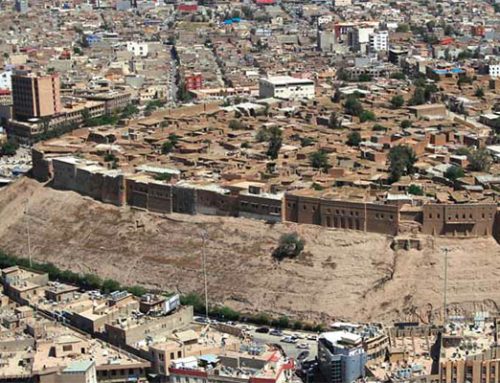

Work continues at Shahr-i-Sokhta, while the standing walls uncovered during earlier campaigns have been preserved. The site was composed of many large structures, including palaces, several large villas, and more modest homes.

By 2000 b.c. these settlements were abandoned. The reasons for this remain unclear and are the source of much scholarly controversy, but urban life didn’t return to eastern Iran for more than 1,500 years. The very existence of this civilization was long forgotten. Recovering its past has not been easy. Parts of the area are close to the Afghan border, long rife with armed smugglers. Revolution and politics have frequently interrupted excavations. And the immensity of the region and its harsh climate make it one of the most challenging places in the world to conduct archaeology.

The peripatetic English explorer Sir Aurel Stein, famous for his archaeological work surveying large swaths of Central Asia and the Middle East, slipped into Persia at the end of 1915 and found the first hints of eastern Iran’s lost cities. Stein traversed what he described as “a big stretch of gravel and sandy desert” and encountered “the usual…robber bands from across the Afghan border, without any excit•ing incident.” What did excite Stein was the discovery of what he called “the most surprising prehistoric site” on the eastern edge of the Dasht-e Lut. Locals called it Shahr-i-Sokhta (“Burnt City”) because of signs of ancient destruction.

It wasn’t until a half-century later that Tosi and his team hacked their way through the thick salt crust and discovered a metropolis rivaling those of the first great urban centers in Mesopotamia and the Indus. Radiocarbon data showed that the site was founded around 3200 b.c., just as the first substantial cities in Mesopotamia were being built, and flourished for more than a thousand years. During its heyday in the middle of the third millennium b.c., the city covered more than 150 hectares and may have been home to more than 20,000 people, perhaps as populous as the large cities of Umma in Mesopotamia and Mohenjo-Daro on the Indus River. A vast shallow lake and wells likely provided the nec•essary water, allowing for cultivated fields and grazing for animals.

It wasn’t until a half-century later that Tosi and his team hacked their way through the thick salt crust and discovered a metropolis rivaling those of the first great urban centers in Mesopotamia and the Indus. Radiocarbon data showed that the site was founded around 3200 b.c., just as the first substantial cities in Mesopotamia were being built, and flourished for more than a thousand years. During its heyday in the middle of the third millennium b.c., the city covered more than 150 hectares and may have been home to more than 20,000 people, perhaps as populous as the large cities of Umma in Mesopotamia and Mohenjo-Daro on the Indus River. A vast shallow lake and wells likely provided the nec•essary water, allowing for cultivated fields and grazing for animals.

Built of mudbrick, the city boasted a large palace, separate neighborhoods for pottery-making, metalworking, and other industrial activities, and distinct areas for the production of local goods. Most residents lived in modest one-room houses, though some were larger compounds with six to eight rooms. Bags of goods and storerooms were often “locked” with stamp seals, a procedure common in Mesopotamia in the era.

Shahr-i-Sokhta boomed as the demand for precious goods among elites in the region and elsewhere grew. Though situated in inhospitable terrain, the city was close to tin, copper, and turquoise mines, and lay on the route bringing lapis lazuli from Afghanistan to the west. Craftsmen worked shells from the Persian Gulf, carnelian from India, and local metals such as tin and copper. Some they made into finished products, and others were exported in unfinished form. Lapis blocks brought from the Hindu Kush mountains, for example, were cut into smaller chunks and sent on to Mesopotamia and as far west as Syria. Unworked blocks of lapis weighing more than 100 pounds in total were unearthed in the ruined palace of Ebla, close to the Mediterranean Sea. Archaeologist Massimo Vidale of the University of Padua says that the elites in eastern Iranian cities like Shahr-i-Sokhta were not simply slaves to Mesopotamian markets. They apparently kept the best-quality lapis for themselves, and sent west what they did not want. Lapis beads found in the royal tombs of Ur, for example, are intricately carved, but of generally low-quality stone compared to those of Shahr-i-Sokhta.

Pottery was produced on a massive scale. Nearly 100 kilns were clustered in one part of town and the craftspeople also had a thriving textile industry. Hundreds of wooden spindle whorls and combs were uncovered, as were well-preserved textile fragments made of goat hair and wool that show a wide variation in their weave. According to Irene Good, a specialist in ancient textiles at Oxford University, this group of textile fragments constitutes one of the most important in the world, given their great antiquity and the insight they provide into an early stage of the evolution of wool production. Textiles were big business in the third millennium b.c., according to Mesopotamian texts, but actual textiles from this era had never before been found.

Situated at the end of a small delta on a dry plain, Shahdad was excavated by an Iranian team in the 1970s (below). An Iranian-Italian team (bottom), including archaeologist Massimo Vidale (right), surveyed the site in 2009.

The artifacts also show the breadth of Shahr-i-Sokhta’s connections. Some excavated red-and-black ceramics share traits with those found in the hills and steppes of distant Turkmenistan to the north, while others are similar to pots made in Pakistan to the east, then home to the Indus civilization. Tosi’s team found a clay tablet written in a script called Proto-Elamite, which emerged at the end of the fourth millennium b.c., just after the advent of the first known writing system, cuneiform, which evolved in Mesopotamia. Other such tablets and sealings with Proto-Elamite signs have also been found in eastern Iran, such as at Tepe Yahya. This script was used for only a few centuries starting around 3200 b.c. and may have emerged in Susa, just east of Mesopotamia. By the middle of the third millennium b.c., however, it was no longer in use. Most of the eastern Iranian tablets record simple transactions involving sheep, goats, and grain and could have been used to keep track of goods in large households.

|

Burial GoodsIf there were any doubts that eastern Iran was a sophisticated and populous region in the third millennium b.c., the vast cemetery at Shahr-i-Sokhta has put them to rest. Over the past two decades, a team led by Iranian archaeologist Mansour Sajjadi has been working in a 100-acre area that includes an estimated 40,000 graves—and possibly as many as 200,000—dug over a period of many centuries, only 100 of which have thus far been exca-vated.According to archaeologist Kirsi Lorentz at the University of Newcastle, who is working on the finds from the site, the cemetery offers “a unique record with which to study the development of urban civilization in the third millennium b.c.” One of the most intriguing finds is the well-preserved remains of a woman in her late 20s who died between 2900 and 2800 b.c. She was buried with an ornate bronze mirror and what Sajjadi and Ital-ian excavators believe is an artificial eyeball made of bitumen paste and gold that was once held in place with fine thread. Microscopic examination showed that the artificial eyeball left an imprint in her eye socket, a sign that it was there for a long period of time before her death. Other archaeologists insist that the object is more likely an eyepatch held in place by string threaded through holes on each side. Another important find was an intricate rectangular wooden board with 60 small, round pieces made from wood inlaid with bone and limestone, likely an early form of backgammon. Similar sets have been found in the Indus far to the east, as well as in the tomb of Queen Puabi in the Royal Graves of Ur. The board in Shahr-i-Sokhta is approximately the same date as the Indus and Mesopotamian artifacts, and suggests that the people of eastern Iran traded not only goods, but ideas for entertainment as well. Lorentz says that the cemetery’s large numbers will allow for statistical analysis of health, diet, and mobility among the ancient residents. And though the bones are often in poor condition, she adds that there is “exceptional preservation” of human hair, nails, and skin. Grooves found in the teeth of many individuals may be a sign that weavers used their teeth as third hands. Short hair found on the skulls may show that crew cuts were the fashion—at least in death if not in life. —A.L. |

While Tosi’s team was digging at Shahr-i-Sokhta, Iranian archaeologist Ali Hakemi was working at another site, Shahdad, on the western side of the Dasht-e Lut. This settlement emerged as early as the fifth millennium b.c. on a delta at the edge of the desert. By the early third millennium b.c., Shahdad began to grow quickly as international trade with Meso•potamia expanded. Tomb excavations revealed spectacular artifacts amid stone blocks once painted in vibrant colors. These include several extraordinary, nearly life-size clay statues placed with the dead. The city’s artisans worked lapis lazuli, silver, lead, turquoise, and other materials imported from as far away as eastern Afghanistan, as well as shells from the distant Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean.

Evidence shows that ancient Shahdad had a large metalworking industry by this time. During a recent survey, a new generation of archaeologists found a vast hill—nearly 300 feet by 300 feet— covered with slag from smelting copper. Vidale says that analysis of the copper ore suggests that the smiths were savvy enough to add a small amount of arsenic in the later stages of the process to strengthen the final product. Shahdad’s metalworkers also created such remarkable artifacts as a metal flag dating to about 2400 b.c. Mounted on a copper pole topped with a bird, perhaps an eagle, the squared flag depicts two figures facing one another on a rich background of animals, plants, and goddesses. The flag has no parallels and its use is unknown.

Vidale has also found evidence of a sweet-smelling nature. During a spring 2009 visit to Shahdad, he discovered a small stone container lying on the ground. The vessel, which appears to date to the late fourth millennium b.c., was made of chlorite, a dark soft stone favored by ancient artisans in southeast Iran. Using X-ray diffraction at an Iranian lab, he discovered lead carbonate—used as a white cosmetic—sealed in the bottom of the jar. He identified fatty material that likely was added as a binder, as well as traces of coumarin, a fragrant chemical compound found in plants and used in some perfumes. Further analysis showed small traces of copper, possibly the result of a user dipping a small metal applicator into the container.

|

| A metal flag found at Shahdad, one of eastern Iran’s early urban sites, dates to around 2400 b.c. The flag depicts a man and woman facing each other, one of the recurrent themes in the region’s art at this time. |

Other sites in eastern Iran are only now being investigated. For the past two years, Iranian archae•ologists Hassan Fazeli Nashli and Hassain Ali Kavosh from the University of Tehran have been digging in a small settlement a few miles east of Shahdad called Tepe Graziani, named for the Italian archaeologist who first surveyed the site. They are trying to understand the role of the city’s outer settlements by examining this ancient mound, which is 30 feet high, 525 feet wide, and 720 feet long. Excavators have uncovered a wealth of artifacts including a variety of small sculptures depicting crude human figures, humped bulls, and a Bactrian camel dating to approximately 2900 b.c. A bronze mirror, fishhooks, daggers, and pins are among the metal finds. There are also wooden combs that survived in the arid climate. “The site is small but very rich,” says Fazeli, adding that it may have been a prosperous suburban production center for Shahdad.

Sites such as Shahdad and Shahr-i-Sokhta and their suburbs were not simply islands of settlements in what otherwise was empty desert. Fazeli adds that some 900 Bronze Age sites have been found on the Sistan plain, which borders Afghanistan and Pakistan. Mortazavi, meanwhile, has been examining the area around the Bampur Valley, in Iran’s extreme southeast. This area was a corridor between the Iranian plateau and the Indus Valley, as well as between Shahr-i-Sokhta to the north and the Persian Gulf to the south. A 2006 survey along the Damin River identified 19 Bronze Age sites in an area of less than 20 square miles. That river periodically vanishes, and farmers depend on underground

channels called qanats to transport water.

Despite the lack of large rivers, ancient eastern Iranians were very savvy in marshaling their few water resources. Using satellite remote sensing data, Vidale has found remains of what might be ancient canals or qanats around Shahdad, but more work is necessary to understand how inhabitants supported themselves in this harsh climate 5,000 years ago, as they still do today.

| This plain ceramic jar, found recently at Shahdad, contains residue of a white cosmetic whose complex formula is evidence for an extensive knowledge of chemistry among the city’s ancient inhabitant |

Meanwhile, archaeologists also hope to soon continue work that began a decade ago at Konar Sandal, 55 miles north of Yahya near the modern city of Jiroft in southeastern Iran. France-based archaeologist Yusef Madjizadeh has spent six seasons working at the site, which revealed a large city centered on a high citadel with massive walls beside the Halil River. That city and neighboring settlements like Yahya produced artfully carved dark stone vessels that have been found in Mesopotamian temples. Vidale notes that Indus weights, seals, and etched carnelian beads found at Konar Sandal demonstrate connections with that civilization as well.

Many of these settlements were abandoned in the latter half of the third millennium b.c., and, by 2000 b.c., the vibrant urban life of eastern Iran was history. Barbara Helwig of Berlin’s German Archaeological Institute suspects a radical shift in trade patterns precipitated the decline. Instead of moving in caravans across the deserts and plateau of Iran, Indus traders began sailing directly to Arabia and then on to Mesopotamia, while to the north, the growing power of the Oxus civilization in today’s

The large eastern Iranian settlement of Tepe Yahya produced clear evidence for the manufacture of a type of black stone jar for export that has been found as far away as Mesopotamia

Turkmenistan may have further weakened the role of cities such as Shahdad. Others blame climate change. The lagoons, marshes, and streams may have dried up, since even small shifts in rainfall can have a dramatic effect on water sources in the area. Here, there is no Nile, Tigris and Euphrates, or Indus to provide agricultural bounty through a drought, and even the most sophisticated water systems may have failed during a prolonged dry spell.

Unbaked clay figurines like this one, dated to 2400–2000 b.c., were found in several graves at Shahdad. Unbaked clay figurines like this one, dated to 2400–2000 b.c., were found in several graves at Shahdad. |

It is also possible that an international economic downturn played a role. The destruction of the Mesopotamian city of Ur around 2000 b.c. and the later decline of Indus metropolises such as Mohenjo-Daro might have spelled doom for a trading people. The market for precious goods such as lapis collapsed. There is no clear evidence of widespread warfare, though Shahr-i-Sokhta appears to have been destroyed by fire several times. But a combination of drought, changes in trade routes, and economic trouble might have led people to abandon their cities to return to a simpler existence of herding and small-scale farming. Not until the Persian Empire rose 1,500 years later did people again live in any large numbers in eastern Iran, and not until modern times did cities again emerge. This also means that countless ancient sites are still awaiting exploration on the plains, in the deserts, and among the rocky valleys of the region.

Andrew Lawler is a contributing editor at Archaeology. For our 1975 coverage of the excavations at Shahr-i-Sokhta, see www.archaeology.org/iran

Lasting Impression

They are tiny and often faded and fragmented. But one abundant source of evidence for both international trade and the role of women in eastern Iran during the third millennium b.c. are the tiny images found on seals and seal-ings throughout this area. The small impressions were designed to mark ownership and control of goods, from bags of barley to a storeroom filled with oil jugs. Holly Pittman, an art historian at the University of Pennsylva-nia who has worked throughout the Middle East and Central Asia, is examining the fragile impressions. She is attempting to build a clearer picture of the lives of ancient inhabitants in large centers such as Shahr-i-Sokhta, Shahdad, and Konar Sandal, near today’s modern city of Jiroft. Pittman now believes these people of eastern Iran shared common ideas and beliefs while also participating in the first age of long-distance exchange. Female deities with vegetation growing out of their bodies are one common element on the seals found in eastern Iran and, as on the Shahdad flag, figures confronting one another also appear frequently. A distinctive type of white stone seals that have been found in Central Asia and the Indus appear to have been made in a similar style by eastern Iranians. “There are relationships between sites, and certainly this part of eastern Iran is participat-ing in a global network,” she says. “This is a world of merchants and traders.” Pittman believes that by early in the third millennium b.c., the network linking Mesopotamia and southeastern Iran resulted in a mixing of cultures across this enormous area. Seals that were used to close storage rooms in Konar Sandal, for example, are of a specific Mesopotamian type common in the major Iraqi port of Ur. That hints strongly at the presence of Mesopotamian inhabit-ants in Konar Sandal who had almost certainly come from Ur. She also suggests that Mesopotamian artifacts absorbed style elements from southeastern Iran. Another example is the famous inlaid lyre found at Ur, which has the face of a bearded bull typical of eastern Iran. Other seals found in ruins such as Konar Sandal are Proto- Elamite in style, showing strong connections with western and central Iran, where the Proto-Elamite writing system is believed to have originated at the same time that Mesopotamian urban life began to flourish in the late fourth millennium b.c. Seals were powerful markers of economic, political, and social clout. At some eastern Iranian sites such as Shahr-i-Sokhta, they appear to have been largely in the hands of women. Marta Ameri, an archaeologist at the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York, notes that two-thirds of the seals found in Shahr-i-Sokhta’s graves are found in female burials. While the grander bronze seals are uncovered mostly in male tombs, the more common bone seals are more often associated with women. Based on remains of seal-ings made to doors, vases, bags, and other objects, the bone seals were in more frequent use than the bronze. This suggests, Ameri says, that women were in control of food storage and possibly trade goods as well. Until more intact graves are found at other sites such as Shahdad,“we at least have a tantalizing look at the roles women may have played,” says Ameri. —A.L. |