Two centuries of excavations on six continents have given voice to a past that previously lay mostly hidden. Now breakthroughs in technology promise even more revelations.

By Andrew Lawler, Published October 21, 2021

Digging for treasure is as old as the first plundered grave.

The urge to uncover buried wealth has obsessed countless searchers, enriching a few and driving others to the brink of madness.

“There are certain men who spend nearly all their lives in seeking for—kanûz—hidden treasures,” wrote the British traveler Mary Eliza Rogers after she visited Palestine in the middle of the 19th century. “Some of them become maniacs, desert their families, and though they are often so poor that they beg their way from door to door, and from village to village, they believe themselves to be rich.”

Not all the fortune hunters whom Rogers came across were desperate vagabonds. She also encountered sahiri, roughly translated as necromancers, “who are believed to have the power of seeing objects concealed in the earth.” These esteemed clairvoyants, often women, entered a trance that Rogers said allowed them to describe in minute detail the hiding places of valuable goods.

Archaeology transformed those “objects concealed in the earth” from simple treasures into powerful tools that allow us to glimpse the hidden past.

At first, the fledgling science emerging in Rogers’s day differed little from old-fashioned plundering, as European colonialists competed to fill their display cabinets with ancient statues and jewelry from faraway lands. But the new discipline also ushered in an unprecedented era of discovery that revolutionized the understanding of our species’ rich diversity, as well as our common humanity.

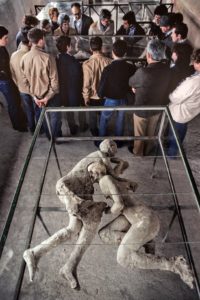

If this seems an exaggeration, imagine a world without archaeology. No luxurious Pompeii. No breathtaking Thracian gold. No Maya cities looming out of dense jungle. A Chinese emperor’s terra-cotta army would still be hidden beneath the dark soil of a farmer’s field.

TERRA-COTTA WARRIORS, 210 B.C. Buried to accompany China’s first emperor in the afterlife, life-size statues of soldiers and servants were discovered by farmers in 1974. Since then, archaeologists have unearthed some 8,000 warriors. Photograph by O. LOUIS MAZZATENTA

Without archaeology, we would know little about the world’s earliest civilizations. Lacking a Rosetta stone, we would still puzzle over the enigmatic symbols on the walls of Egyptian tombs and temples. The world’s first literate and urban society, which flourished in Mesopotamia, would be known only dimly through the Bible. And the largest and most populous of these early cultures, clustered around the Indus River on the Indian subcontinent, would never have been revealed at all.

Without the systematic study of sites and artifacts, history would be held hostage by those few texts and monumental buildings that survived the vagaries of time. The immense Pacific of our past would be broken only by scattered atolls: a battered scroll here, a pyramid there.

Two centuries of excavations on six continents have given voice to a past that previously lay mostly submerged. Through recovered sites and objects, our distant ancestors—many of whom we didn’t know existed—can tell their stories.

That dialogue has grown contentious—and even violent—in the wake of Charlottesville’s white supremacist rally in 2018, centering on statues of Jefferson and Confederate leaders, that turned deadly. The debate intensified after the May 2020 death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police sparked protests and riots across the nation. The half-dozen rebel memorials on Richmond’s famed Monument Avenue, for example, came down in the summer of 2020. The remaining statue, of Confederate General Robert E. Lee, was removed earlier this month after a legal case that went to the Virginia Supreme Court.

Thompson estimates that some 170 monuments—less than half of one percent— were dismantled in the wake of Floyd’s death. More than 80 percent of those were removed as the result of decisions by municipalities, while the remainder were toppled by demonstrators. The vast majority were memorials to Confederate leaders or increasingly divisive figures like Columbus. (See how memorials to 9/11 help us remember and mourn.)

The monument audit confirmed that 99.4 percent of American monuments remain securely on their plinths following the upheavals of the last year. It also emphasizes that monuments as a group have never been static, and that over time hundreds have been moved, altered, or taken down for a wide variety of reasons—from community repugnance to road construction. “When power shifts and values evolve, monuments are replaced,” said Greg Werkheimer, a cultural heritage attorney in Richmond involved with the dismantling of Confederate statues there.

TOMB OF A TEENAGE PHARAOH, 1322 B.C. After archaeologist Howard Carter opened King Tut’s treasure-filled tomb in Egypt in 1922, the young pharaoh became a global celebrity. His gold funerary mask is a star attraction at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. Photograph by KENNETH GARRETT

At least as far back as the last king of Babylon, more than 2,500 years ago, rulers and the rich have collected antiquities to bask in the reflected beauty and glory of previous times. Roman emperors transported at least eight Egyptian obelisks across the Mediterranean to embellish their capital. During the Renaissance, one of these pagan monuments was raised in the heart of St. Peter’s Square.

In 1710, a French aristocrat paid workers to tunnel through Herculaneum, a town near Pompeii that had lain largely undisturbed since the deadly explosion of Vesuvius in A.D. 79. The unearthed marble statues sparked a craze that spread across Europe for digging up ancient sites. In the New World, Thomas Jefferson had trenches cut through a Native American burial mound not to find lucrative grave goods but to assess who built it and why.

LAST MOMENTS OF POMPEII AND HERCULANEUM, A.D. 79 Touring Pompeii in 1981, a group studies victims of the volcanic eruption of Mount Vesuvius that entombed two wealthy Roman towns. “Suddenly we are faced with human beings out of the dim past. Photograph by DAVID HISER

By Mary Eliza Rogers’s day, European excavators were fanning out across the globe. Few were dedicated scholars. More often than not, they were diplomats, military officers, spies, or wealthy businessmen (and they were, with very few exceptions, men) intimately tied to colonial expansion. They used their influence and power abroad to both study and steal, as they filled their notebooks and carted off Egyptian mummies, Assyrian statues, and Greek friezes for their national museums or private collections.

Fast-forward to the Roaring Twenties. The spectacular bling found in the tomb of the Egyptian king Tut and the Royal Graves of Ur captured headlines and altered the course of art, architecture, and fashion. By then, however, educated professionals had begun to grasp that the most valuable material from trenches lay not in the gold retrieved but in the data locked within broken pottery and discarded bones.

New methods of recording fine layers of soil provided novel ways to reconstruct day-to-day life. And starting in the 1950s, measuring the radioactive decay of organic matter gave researchers their first reliable clock to date artifacts.

In our own century, archaeology increasingly is done less in the trench than in the lab. What once had little obvious worth—burnt seeds, human feces, the residue at the bottom of a pot—is the new treasure. Through careful analysis, these humble remains can reveal what people ate, with whom they traded, and even where they grew up.

Advanced techniques are even capable of dating rock art, providing insight into cultures such as those of the early Aboriginal peoples of Australia, who left behind little durable evidence. And the sea is no longer the impenetrable barrier that it had been from time immemorial, as divers gain access to shipwrecks ranging from a Bronze Age merchant vessel to the most legendary of all ocean disasters, the Titanic.

The single most revolutionary development of recent decades is our ability to extract genetic material from old bones. Ancient DNA has given us an intimate glimpse into how our ancestors interacted with Neanderthals. It has also led to the discovery of our long-lost cousins the Denisovans, as well as the extraordinarily small people of the Indonesian island of Flores.

A host of new approaches, from satellite images to x-ray fluorescence, allow scientists to probe sites and artifacts without putting a spade into soil or cutting a sample from a valued museum object. This means that we are less likely to inadvertently wipe out data that we don’t recognize but that later generations might yet recover.

ANGKOR WAT, A.D. 802-1431 At its height in the 13th century, the capital of the Khmer Empire was the most extensive urban site in the world. As archaeologists search for clues to the city’s downfall, the temple complex in Cambodia endures as a revered religious shrine. Photograph by KIKE CALVO

Archaeology’s often unsavory past nevertheless continues to cast a long shadow. Not until the past decade has a movement to repatriate ill-gotten foreign artifacts, from the Elgin Marbles to the Benin Bronzes, gained political traction. For centuries, American and European reluctance to train or promote Indigenous archaeologists meant that when the colonial empires crumbled, there were few homegrown researchers with the experience to carry on the work. Those who struggle to do so often are hindered by war, a lack of resources, and development pressures. One of Central Asia’s great ancient Buddhist centers, Mes Aynak in Afghanistan, has been threatened by looters, rocket attacks, and a government plan to mine the site, which sits atop a vast reserve of copper. In August it fell under Taliban control.

The past is a nonrenewable resource, and every ancient site bulldozed or ransacked is a global loss. It is common wisdom today that local communities are an essential part of maintaining the health and well-being of natural ecosystems such as parks and wildlife preserves. The same applies to what our ancestors left behind.

The destruction that has afflicted sites across the Middle East and Central Asia is all the more terrible because impoverished villagers often have little stake in protecting them. Threats to this heritage include idol-smashing groups such as al Qaeda and the Taliban, as well as the buyers and sellers of looted artifacts. Peace and prosperity also pose dangers, when new construction destroys ancient remains.

Despite daunting setbacks, there is good reason to believe that a second golden age of archaeology—one largely shorn of its colonialist trappings and racist assumptions—has begun.

An influx of women and Indigenous researchers is revitalizing the field, while archaeologists (often an insular bunch) are now working more closely with their colleagues in other disciplines. They are charting global change through the ages with the help of climatologists, collaborating with chemists to trace the ancient spread of drugs such as marijuana and opium, and investigating more precise dating methods with physicists.

Recent finds, meanwhile, show the power of archaeology to radically reshape the way we relate to our past. Göbekli Tepe in Turkey, the world’s oldest known temple, dating back some 12,000 years, suggests that our urge to practice communal religious rites may have spurred us to settle down and plant crops, not the other way around. Egypt’s pyramid builders were not enslaved people but skilled workers who earned decent wages and drank good beer. And ancient DNA paints a jumbled and complicated tale of our ancestors’ journey across the planet that can’t be contained within race theories and national myths.

But archaeology’s real power remains rooted in its capacity to transcend intellectual knowledge and the creeds of the moment. Uncovering what has long been hidden connects us viscerally to our vanished ancestors. In that moment when an excavator brushes away the dirt to reveal an ancient coin or gingerly removes caked soil from a votive statue’s delicately chiseled face, the immense distances of time, culture, language, and beliefs can fall away.

Even if we are just gazing through the glass of a museum case or at the pages of a magazine, we can find ourselves closely linked to the person who shaped a pot, secured a dazzling brooch, or carried a finely wrought sword into battle. There is a haunting poignancy to those 3.7-million-year-old footprints left one rainy day on the Tanzanian savanna, as if we are present at the dawn of our own creation.

The task of archaeologists is not to find buried treasure but to resurrect the long dead, turning them back into individuals who, like us, struggled and loved, created and destroyed, and who, in the end, left behind something of themselves.

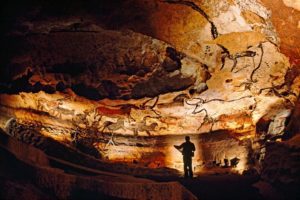

The Lascaux Cave in southwestern France preserves the artwork of Paleolithic painters who evoked on a grand scale the animals they knew nearly 20,000 years ago. Photograph by SISSE BRIMBERG

Ice Age Artists

20,000 years ago, France

On a September afternoon in 1940, four teenage boys made their way through the woods on a hill overlooking Montignac in southwestern France. They had come to explore a dark, deep hole rumored to be an underground passage to the nearby manor of Lascaux. Squeezing through the entrance one by one, they soon saw wonderfully lifelike paintings of running horses, swimming deer, wounded bison, and other beings—works of art that may be up to 20,000 years old.

The collection of paintings in Lascaux is among some 150 prehistoric sites dating from the Paleolithic period that have been documented in France’s Vézère Valley. This corner of southwestern Europe seems to have been a hot spot for figurative art. The biggest discovery since Lascaux occurred in December 1994, when three spelunkers laid eyes on artworks that had not been seen since a rockslide 22,000 years ago closed off a cavern in southern France. Here, by flickering firelight, prehistoric artists drew profiles of cave lions, herds of rhinos and mammoths, magnificent bison, horses, ibex, aurochs, cave bears. In all, the artists depicted 442 animals over perhaps thousands of years, using nearly 400,000 square feet of cave surface as their canvas. The site, now known as Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc Cave, is sometimes considered the Sistine Chapel of prehistory.

For decades scholars had theorized that art had advanced in slow stages from primitive scratchings to lively, naturalistic renderings. Surely the subtle shading and elegant lines of Chauvet’s masterworks placed them at the pinnacle of that progression. Then carbon dates came in, and prehistorians reeled. At some 36,000 years old—nearly twice as old as those in Lascaux—Chauvet’s images represented not the culmination of prehistoric art but its earliest known beginnings.

The search for the world’s oldest cave paintings continues. On the Indonesian island of Sulawesi, for example, scientists found a chamber of paintings of part-human, part-animal beings that are estimated to be 44,000 years old, older than any figurative art seen in Europe.

Scholars don’t know if art was invented many times over or if it was a skill developed early in our evolution. What we do know is that artistic expression runs deep in our ancestry.

In a lab in Bolzano, Italy, scientists use an endoscope to view a lethal arrowhead lodged in the shoulder of Ötzi, the prehistoric iceman. The arrow’s shaft was broken, suggesting Ötzi struggled to extract it or that his killer tried to remove it. Photograph by ROBERT CLARK

Ötzi the Iceman

Circa 3300 B.C., Ötztal Alps, Italy

Frozen in time under a glacier in the Alps, this Neolithic hunter felled by a foe’s arrow about 5,300 years ago is the oldest intact human ever discovered.

In 1991, hikers high in the mountains on Italy’s border with Austria discovered a mummified body protruding from a glacier. Little did they suspect that this “iceman” was a time traveler from the Copper Age. Indeed, further investigation revealed that the 5,300-year-old Ötzi the Iceman—named for the Ötztal Valley near his death site—is the oldest intact human ever found. “Not since Howard Carter unlocked the tomb of King Tutankhamun in the early 1920s had an ancient human so seized the world’s imagination,” wrote mountaineer and author David Roberts.

Over the ensuing three decades, scientists have used an array of high-tech tools, including 3D endoscopy and DNA analysis, to examine the iceman and refine his biography in exquisite detail. What at first appeared to be a tale of a solitary Neolithic hunter overtaken by the elements has morphed into a riveting murder mystery.

He was in his mid-40s, a rather elderly man for his time. He suffered from worn joints, hardened arteries, gallstones, advanced gum disease, and tooth decay. While these health factors made his life uncomfortable, they did not kill him.

In 2001, a radiologist x-rayed Ötzi’s chest and detected a stone arrowhead, smaller than a quarter, lodged beneath the left shoulder blade. The forensic evidence became even more intriguing in 2005, when new CT scan technology revealed that the arrowhead, probably flint, had made a half-inch gash in the iceman’s left subclavian artery. Such a serious wound would have been almost immediately fatal. The conclusion: An attacker, positioned behind and below his target, fired an arrow that struck Ötzi’s left shoulder. Within minutes, the victim collapsed, lost consciousness, and bled out.

For all the answers that scientists have found about the iceman, many questions still remain. At the top of the list: Who killed this prehistoric hunter, and why?

Sudanese camel drivers pass the 2,000-year-old tombs of Nubian kings and queens at Jebel Barkal. Nubian kings ruled over ancient Egypt for about 75 years, reunifying the country and building an empire. Photograph by ENRICO FERORELLI

The Black Pharaohs

730-656 B.C., Sudan and Egypt

In a long-ignored chapter of history, kings from a land to the south conquered Egypt, then kept the country’s ancient burial traditions alive.

In the year 730 B.C., a man named Piye decided the only way to save Egypt from itself was to invade it. The magnificent civilization that had built the Pyramids at Giza had lost its way, torn apart by petty warlords. For two decades Piye had ruled over his own kingdom in Nubia, a swath of Africa located mostly in present-day Sudan. But he considered himself the rightful heir to the traditions practiced by the great pharaohs.

By the end of a yearlong campaign, every leader in Egypt had capitulated. In exchange for their lives, the vanquished urged Piye to worship at their temples, pocket their finest jewels, and claim their best horses. He obliged them and became the anointed Lord of Upper and Middle Egypt.

When Piye died at the end of his decades-long reign, his subjects honored his wishes by burying him in an Egyptian-style pyramid at a site known today as El Kurru. No pharaoh had received such entombment in more than 500 years.

Piye was the first of the so-called Black pharaohs, the Nubian rulers of Egypt’s 25th dynasty. Over the course of 75 years, those kings reunified a tattered Egypt and created an empire that stretched from the southern border at present-day Khartoum all the way north to the Mediterranean Sea.

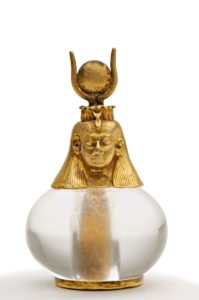

About two inches tall, an amulet found in a Kushite queen’s tomb is topped with a golden head of the Egyptian goddess Hathor. Photograph by KENNETH GARRETT

Until recently, theirs was a chapter of history that largely went untold. “The first time I came to Sudan, people said, You’re mad! There’s no history there! It’s all in Egypt!” says Swiss archaeologist Charles Bonnet. But he and other modern researchers are now revealing the rich history of a long-ignored culture. Archaeologists have recognized that the Black pharaohs didn’t appear out of nowhere. They sprang from a robust African civilization in a land the Egyptians called Kush that flourished on the southern banks of the Nile as far back as the first Egyptian dynasty, around 3000 B.C.

The Egyptians didn’t like having such a powerful neighbor to the south, especially since they depended on Nubia’s gold mines to bankroll their dominance of western Asia. So the pharaohs of the 18th dynasty (1539-1292 B.C.) sent armies to conquer Nubia and built garrisons along the Nile. Subjugated, the elite Nubians began to embrace Egypt’s cultural and spiritual customs—venerating Egyptian gods, using the Egyptian language, and adopting Egyptian burial styles.

The Nubians were arguably the first people to be struck by “Egyptomania.” Without setting foot inside Egypt, they preserved Egyptian traditions and revived the pyramid—a burial monument forsaken by the Egyptians centuries earlier—for their royal tombs. As archaeologist Timothy Kendall puts it, the Nubians “had become more Catholic than the pope.”

Skilled goldsmiths created masterpieces such as this breastplate pendant of the goddess Isis, which lay across the mummy of a Nubian king entombed at Nuri. Photograph by KENNETH GARRETT

In the seventh century B.C., Assyrians invaded Egypt from the north. The Nubians retreated permanently to their homeland, but they continued to mark their royal tombs with pyramids, dotting sites such as El Kurru, Nuri, and Meroë with the steep-sided profiles that characterize their interpretation of ancient Egyptian monuments. Like their mentors, Kushite kings filled their burial chambers with treasure and decorated them with images that would ensure a rich afterlife.

Little was known of these kings until Harvard Egyptologist George Reisner arrived in Sudan in the early 20th century. Reisner located the tombs of five Nubian pharaohs of Egypt and many of their successors. These discoveries, and subsequent investigations, have resurrected from obscurity the first high civilization in sub-Saharan Africa.

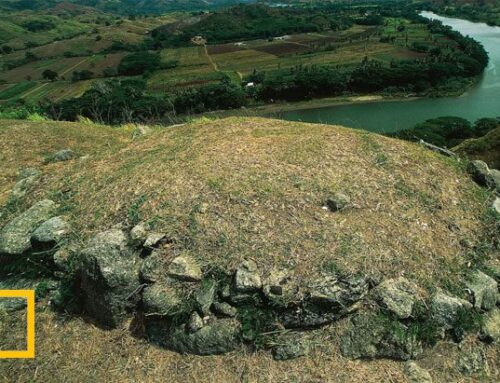

Archaeologists made a stunning discovery in 1989 at the ancient Maya city of Copán in Honduras: the grave of a mighty king and founder of a dynasty that held sway for some 400 years. Photograph by KENNETH GARRETT

A Maya King’s Domain

1000 B.C.–A.D. 900, Honduras

Extraordinary finds at the site of the ancient city of Copán in recent decades have helped archaeologists take a giant step forward in learning about the Maya.

In a tunnel 50 feet below the grassy plazas of Copán, an ancient Maya city in what is now Honduras, National Geographic staff archaeologist George Stuart peered through an opening in a wall of dirt and stone. There, in a hot, stuffy, earthquake-prone space, he saw a skeleton on a large stone slab. Stuart’s archaeological colleagues had discovered a royal burial—most likely that of K’inich Yax K’uk’ Mo’, or Sun-Eyed Green Quetzal Macaw. The revered god-king, whose name appears in many of the site’s hieroglyphic texts, was the founder of a dynasty that maintained the power of this Maya valley kingdom for some 400 years.

Burial goods in the royal grave included this deer-shaped vessel that held chocolate. Photograph by KENNETH GARRETT

That momentous discovery was made in 1989, but Maya scholars had long recognized the enormous significance of Copán. From more than a century of research, they knew that the ruined buildings beside the Copán River served as the political and religious capital of an important kingdom before its collapse more than a thousand years ago. Early on, investigators came to realize that the section now known as the Acropolis—a roughly rectangular area that rises high above the river—served not only as the locus of some of the city’s most spectacular architecture and sculpture but also as the seat of governing power during the height of the Maya Classic period, from about A.D. 400 to 850.

The rulers of Copán claimed descent from the sun and ruled by that right. They presided over a kingdom of some 20,000 subjects, ranging from farmers who lived in pole-and-thatch houses to the elite who occupied palaces near the Acropolis. As the archaeologists tunneled into the Acropolis, they came upon the most elaborately constructed and furnished tomb yet uncovered at the site. The remains of a noble lady rested on a thick rectangle of stone. She was richly attired and wore one of the most extraordinary arrays of Maya jade ever found. She was probably the wife of the founder, archaeologists believe, the queen mother of the next 15 rulers of the Copán dynasty.