Ancient sites in contested areas are more vulnerable to looting and destruction than those in ISIS-controlled territory.

Videos of Islamic State militants shattering ancient statues and blowing up classical temples have shocked the world. But according to a new analysis of satellite images by U.S. archaeologists, these high-profile acts obscure the actual extent of damage to Syria’s rich cultural heritage.

The team examined images of 1,450 ancient sites across the shattered nation and found that one in four has been damaged or looted in the civil war that began in 2011.

More than half of those sites are in rebel-controlled areas, followed by those dominated by Kurdish forces. Damage at sites claimed by the Islamic State, also known as ISIS or ISIL, accounts for a quarter of the destruction, with the remainder in areas loyal to Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

“It is quite evident that overall incidents of looting are much higher in Kurdish and opposition-held areas than in either Syrian regime or ISIL areas,” said Jesse Casana, a Dartmouth University archaeologist who is leading the analysis.

This finding should not be surprising, given that looting tends to spike in places with no civil authority, Casana told a gathering of the American Schools for Oriental Research in Atlanta earlier this month. Contested areas, such as those around the ancient city of Aleppo, have suffered even more extensively than sites under ISIS control.

It is quite evident that overall incidents of looting are much higher in Kurdish and opposition-held areas than in either Syrian regime or ISIL areas.

Archaeologist Jesse Casana

Dartmouth University

Syria boasts more than 6,500 mapped ancient sites that range from Neolithic settlements to medieval mosques. When the team categorized damage as minor, moderate, or severe, sites in ISIS-controlled areas were more likely to have suffered severe damage than those in other parts of Syria. “This could be read as evidence of more organized, potentially state-sanctioned looting in those areas,” Casana added.

The 2,000-year-old Baal temple in Palmyra was destroyed in September after ISIS invaded this desert region. Above, the temple can be seen in the center of the massive platform before the destruction; below shows the site after. PHOTOGRAPH BY DIGITALGLOBE, GETTY IMAGES

Yet chaos has proved even more destructive than ISIS’ publicity campaign to rid its area of ancient monuments. A lack of civil control encourages groups and individuals to dig up artifacts to sell on the international art market. And military action in more contested areas also poses a threat to cultural heritage.

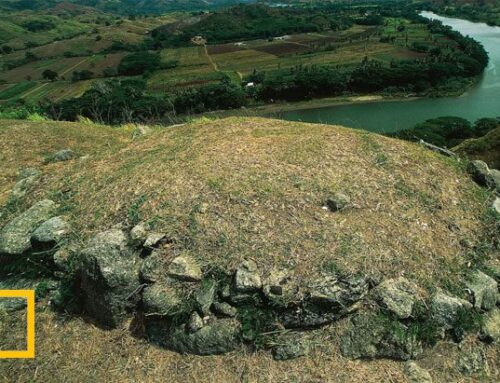

For example, the human-made mounds that dot the Syrian landscape, remnants of ancient settlements, can serve as strategic defenses. Casana’s team tracked bulldozers constructing troop garrisons at sites like Tell Jifar, which is under Syrian government control. That site also has been severely looted, either with the approval or involvement of government troops there.

“The extreme actions by ISIL have led to understandable outrage across the globe,” said Casana. “But our focus on ISIL has also led to some misunderstandings about the scope of the antiquities crisis in the region, and about who is responsible for it, and therefore how best to address it.”

Elise Laugier, an archaeologist at the University of Arkansas also working on the assessment, which is still ongoing, added that there has been as much looting in Syria in the past five years as in all the decades prior to the conflict.

Looting by Decree

Ironically, the lower percentage of looting in areas controlled by ISIS appears to be the result of the self-serving order the terrorist group has imposed on northern and eastern Syria. “They have a framework to regulate looting and punish those who don’t get looting permits,” said Casana.

In May, U.S. Special Forces raided a village in eastern Syria in the search for a senior ISIS official named Abu Sayyaf. He was killed in the ensuing shootout, and the military team captured artifacts—many of them fake—as well as a cache of documents that revealed ISIS complicity in the antiquities trade.

Chaos has proved even more destructive than ISIS’ publicity campaign to rid its area of ancient monuments.

According to the documents released by the U.S. State Department, Sayyaf was in charge of the antiquities division of ISIS’ Diwan of Natural Resources, which also oversees oil. Sayyaf was the official who provided permits for looters within Syria.

ISIS officials confirmed this in September in a memo from its General Committee. “It is prohibited for any brother from the Islamic State to excavate antiquities or give the permit to anyone from the public without receiving a stamped permit.”

Aleppo once was home to one of the finest collections of medieval architecture in the Middle East. After a November 7 attack by the Syrian army, residents of the city’s Salahiye neighborhood dig through the rubble. PHOTOGRAPH BY IBRAHIM EBU LEYS, ANADOLU AGENCY, GETTY IMAGES

Permit holders are expected to give 20 percent of their profits to ISIS—a traditional Islamic “war booty” fee—or face punishment. According to the captured memos, in the four months leading up to April, ISIS received $265,000 in taxes on total sales of $1.25 million.

“That is just one snapshot” of a limited period of time, said Andrew Keller, a U.S. State Department official who monitors ISIS revenue streams. In a September speech, he added that the total figure for that period is likely much higher, and that ISIS “does not just passively tax the sale of antiquities by others. It actively controls the trade to ensure maximum profits.”

Permit holders are expected to give 20 percent of their profits to ISIS—a traditional Islamic “war booty” fee—or face punishment.

He estimates that the organization has made several million dollars from antiquities sales since mid-2014, but the precise amount is unknown.

The U.S. government is now trying to shut down these looting networks in part by offering up to $5 million for information leading to the significant disruption of the antiquities flowing out of Syria, said Andrew Cohen, an official at the State Department who spoke at the Atlanta meeting.

Low Priority

Given that ISIS beheaded a Syrian archaeologist at the classical site of Palmyra earlier this year, researchers dare not stray into its territory. This limitation makes satellite images vital for tracking the crisis.

While Casana’s team is examining photos, some more than a year old, other archaeologists and cultural heritage experts at the conference complained that they are stymied in attempts to monitor the situation in a more timely way.

“We are crying out for images,” said Scott Branting, director of mapping and data integration for the American Schools of Oriental Research’s Cultural Heritage Initiatives.

He said that the problem is that the U.S. Department of Defense puts cultural heritage low on its priority list. “There is a pecking order, and military priorities can block us.”

He added that satellite photos that his group does obtain can often be six to nine months old. Even for targets important to the military, cultural heritage analysts often remain in the dark about the current situation. Aleppo, for example, is home to a medieval souk and ancient citadel that have been at the heart of fighting, but Branting’s group has been unable to obtain any recent images. “This is a major bottleneck,” he adds.

To overcome this obstacle, Branting proposes “a suite of satellites” that would focus solely on cultural heritage imaging. The spacecraft could be based on the CubeSat series. These are small and can be built with off-the-shelf components, and are popular with academic researchers looking for low-cost access to space.

Branting acknowledges that the time and funding required to build and launch a satellite series would take years and tens of millions of dollars, but he argues it could offer a long-term solution for researchers who want to monitor cultural heritage sites under threat on a regular basis.