Artifacts suggest some members of ill-fated English settlement survived and assimilated with Native Americans.

European artifacts, including (clockwise from top left) pieces of a slate writing tablet, clay tobacco pipes, a stoneware vessel, and a German token could help pinpoint where colonists retreated after abandoning Roanoke Island, North Carolina. PHOTOGRAPH BY MARK THIESSEN, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

The search began when an anxious Englishman named John White waded ashore on North Carolina’s Roanoke Island 425 years ago this month. Appointed governor of the fledgling Roanoke colony by Sir Walter Raleigh, White was returning from England with desperately needed supplies.

But when he stepped ashore on August 18, 1590, he found the settlement looted and abandoned. The vanished colonists had left behind only two clues to their whereabouts: the word “Croatoan” carved on a prominent post and “Cro” etched into a tree.

Ever since, explorers, historians, archaeologists, and enthusiasts have sought to discover the fate of the 115 men, women, and children who were part of England’s first attempt to settle the New World. Efforts to solve America’s longest running historical mystery, dubbed the Lost Colony, produced dozens of theories but no clear answers.

Now two independent teams say they have archaeological remains that suggest at least some of the abandoned colonists may have survived, possibly splitting into two camps that made their homes with Native Americans.

The evidence is that they assimilated with the Native Americans but kept their goods.

Mark Horton, archaeologist

A collection of newly discovered European objects, including a sword hilt, broken English bowls, and a fragment of a slate writing tablet still inscribed with a letter, could point to the presence of the colonists on Hatteras Island, some 50 miles (80 kilometers) southeast of their settlement on Roanoke Island, as well as at a site on the mainland 50 miles to the northwest.

Pictures: Lost Colony Artifacts

- A lump of smelted copper ore found on Roanoke Island is strong evidence of metallurgical work by Europeans in the late 16th century, since Native Americans lacked smelting technology. PHOTOGRAPH BY MARK THIESSEN, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

- This small copper eyelet, discovered in July at the Cape Creek site on Hatteras, might have been used in an article of Elizabethan clothing. PHOTOGRPAH BY MARK THIESSEN, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

- European metallurgists would have used weights like this, found on Roanoke Island at what has been dubbed a science center, to measure materials they were testing. PHOTOGRAPH BY MARK THIESSEN, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

- This lump of European copper was probably imported for trade with Native Americans. Since early 17th century trade typically used copper sheets, archaeologist Mark Horton argues that the bun may be from the time of the Roanoke colony. PHOTOGRAPH BY MARK THIESSEN, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

- Gun parts were among the artifacts discovered at the Cape Creek site during excavations in 1998 during a dig of a Native American site. The object could be part of a weapon made in Elizabethan England. PHOTOGRAPH BY MARK THIESSEN, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

- A peach pit unearthed at the Cape Creek site on Hatteras Island may date to the 16th century. Peaches are native to the Old World, and European settlers brought them to America. PHOTOGRAPH BY MARK THIESSEN, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

- Part of a crucible—perhaps used by 16th-century English metallurgists—was dug from an earthen mound on Roanoke Island in the early 1990s by Ivor Noel Hume. PHOTOGRAPH BY MARK THIESSEN, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

- The copper necklace from Roanoke Island was strung together by short, knotted cords, which rotted away long ago. PHOTOGRAPH MARK THIESEN, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC CREATIVE

- Copper plates made in Europe were once tied together into a necklace for Native Americans. The artifact discovered on Roanoke Island in 2008 by a First Colony Foundation team is one of the few items found there that may date to the 16th century. PHOTOGRAPH BY MARK THIESSEN, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

- Part of an iron rapier handle was unearthed in the spring of 2015 at the Cape Creek site on Hatteras Island. Such weapons were used by Englishmen of high status. PHOTOGRAPH BY MARK THIESSEN

“The evidence is that they assimilated with the Native Americans but kept their goods,” says Mark Horton, an archaeologist at Britain’s Bristol University, who heads the excavation on Hatteras.

Meanwhile, at the mainland site on the Albemarle Sound near Edenton, N.C., Nick Luccketti of the First Colony Foundation believes that his group has unearthed pottery used by the lost colonists after they deserted their Roanoke settlement.

Members of both teams admit they can’t yet claim to have solved the vexing riddle. And many of their colleagues are skeptical that the artifacts can be definitively tied to the ill-fated colonists, given difficulties in dating them precisely.

“You have more work to do,” warned Ivor Noel Hume, a former Colonial Williamsburg archaeologist who excavated at Roanoke Island in the 1990s. Hume met with Horton and Luccketti last month to discuss their finds.

Picture of Gov. John White’s 1585 map of the area from today’s Cape Henry, Va, to Cape Lookout, N.C.

Governor John White’s 1585 map of the area from today’s Cape Henry, Virginia, to Cape Lookout, North Carolina, was remarkably accurate. In 2012 researchers discovered a symbol hidden beneath a patch that may have marked the location of a fort.

© THE TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM

MORE ON THE LOST COLONY

Learn how Governor John White’s map reignited the search for the colonists

But the digs signal an important shift away from Roanoke Island, where researchers have found frustratingly few signs of an early European presence.

A Gentleman’s Ring

“Hey, a chunk of iron!” exclaims Margaret Dawson, a nurse and volunteer excavator, as she sorts through black earth at a site on Hatteras Island called Cape Creek. She and her husband Scott, a local teacher, founded the Croatoan Archaeological Society—named after the island’s native inhabitants—in 2009 and have sponsored Horton’s annual digs ever since.

Hidden in a live oak forest close to Pamlico Sound, Cape Creek was the site of a major Croatoan town and trade hub. Under Horton’s supervision, volunteers are busy searching through fine-mesh screens filled with mud from a nearby trench. The Dawson’s two young daughters are quick to spot tiny Venetian glass beads.

During a two-day excavation in July, the sieves produced ample Native American as well as European materials, including deer and turtle bones, homemade and imported brick, Native American pottery, hunks of European iron, parts of a 16th century gun, and a tiny copper eyelet that may have been used in clothing.

In 1998, archaeologists from East Carolina University found a ten-carat gold signet ring here engraved with a prancing lion or horse, an unprecedented find in early British America. The well-worn object may date to the 16th century and was almost certainly owned by an English nobleman.

Like most of the European finds at Cape Creek, however, the artifact was mixed in with objects that date to the mid-17th century, a full lifetime after the Roanoke colony was abandoned.

Horton argues that members of the lost colony living among the Croatoan may have kept their few heirlooms even as they slowly adopted Indian ways.

A gold signet ring excavated from the Cape Creek site on Hatteras Island, engraved with a prancing lion or horse, may have belonged to a prominent member of the Roanoke colony.

PHOTOGRAPH BY MARK THIESSEN, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

One of the most unusual recent discoveries is a small piece of slate that was used as a writing tablet, along with a lead pencil. A tiny letter “M” can just be made out on one corner. A similar, though much larger, slate was found at Jamestown.

“This was owned by somebody who could read or write,” Horton says. “This wasn’t useful for trade, but was owned by an educated European.”

Another artifact unearthed recently at Cape Creek is part of the hilt of a rapier, a light sword of a type used in England in the late 16th century. In addition, a large copper ingot, a long iron bar, and German stoneware show up in what appear to be late 16th century levels. These may be signs of metallurgical work by Europeans—and possibly by Roanoke settlers—since Native Americans lacked this technology.

“There are trade items here,” Horton says, gesturing at the artifacts. “But there is also material that doesn’t come from trade.” Were these the personal possessions of the colonists?

Does X Mark the Spot?

If the gold ring inspired Horton’s digs on Hatteras, then a 1585 watercolor map drawn by White prompted the First Colony Foundation to turn its attention to the mainland.

Known as La Virginea Pars map and part of the British Museum’s permanent collection, the document made headlines in 2012 when researchers discovered a tiny, four-pointed star hidden under a patch layered atop the map. One theory is that the symbol may have marked the location of an inland fort.

“We think this represents the Roanoke colonists,” says Luccketti, holding out two slivers of green pottery.

If such a fort was built in that location, or even planned or discussed, then it might have been a logical destination for at least some of the displaced colonists.

“We think this represents the Roanoke colonists,” says Luccketti, holding out two slivers of green pottery. The shards were found on a recent weekend excavation at what the First Colony Foundation calls Site X, on the Albemarle Sound.

Picture of Pieces of English pottery called Border Ware

Pieces of English pottery called Border Ware recently found at a site near Edenton, North Carolina, may shed light on the Lost Colony’s fate. The dig by the First Colony Foundation led by archaeologist Nick Luccketti follows new revelations from the 1585 White map.

PHOTOGRAPH BY MARK THIESSEN, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

In 2006, Luccketti and his colleague Clay Swindell from the Museum of the Albemarle investigated a site in the vicinity of the fort icon spotted later on White’s map. There they found a massive quantity of Indian pottery. Archaeologists suspect the site is a small Native American town named Mettaquem.

More recently, in an area adjacent to the village, the First Colony team uncovered English pottery similar to that dug up on Roanoke Island and common at Jamestown—but not typical in the second half of the 17th century, when English settlers filtered south from Virginia to settle North Carolina. Other pottery typical of the later 17th century is absent.

Excavators also found a metal hook possibly used to stretch hides or tents, as well as an aglet, a tiny copper tube used to secure wool fibers. Aglets were largely replaced with hook and eyes in the first half of the 17th century. They’ve shown up on Roanoke Island and at Cape Creek as well.

In all the team has found 275 pounds (125 kilograms) of Indian pottery covering several centuries of settlement, Swindell says. The English material—called Border Ware—accounts for a few dozen pieces amount to three or four pots.

He notes that the first recorded English settler in the area did not arrive until about 1655. Luccketti adds that, unlike the Cape Creek site, there are no obvious trade goods that suggest exchange instead of resident colonists. He thinks that the colonists may have moved here to live among Indian allies after White’s departure.

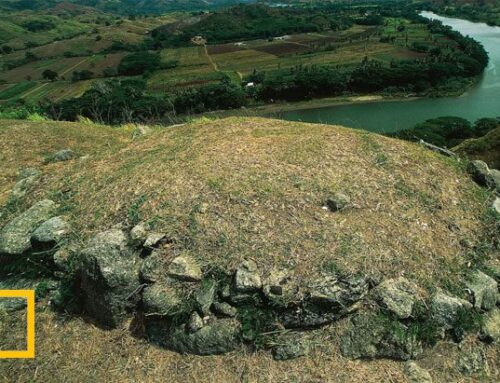

Picture of Professor Mark Horton at the Cape Creek site

Archaeologist Mark Horton oversaw a recent dig at the Cape Creek site on Hatteras Island. He argues that many of the European artifacts discovered here may be associated with the lost colonists.

PHOTOGRAPH BY MARK THIESSEN, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

But Brett Riggs, an archaeologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill not involved with the dig, notes that Native Americans were quick to scavenge any material left by Europeans.

“Anything of utility they took back to their homes,” he says. “They would vacuum it all up.” Even bottle glass was valuable for shaping arrowheads. He warns that European goods don’t equate to European settlers.

Foundation volunteers admit they have not clinched their case. “What we’ve found is tantalizing,” says Martha Williams, as she pauses from her work sifting soil on a recent morning at Site X. “I would love to see some definitive evidence, but what we have is fragmentary.”

We still don’t know what happened, and we are waiting to be persuaded.

Charles Ewen, archaeologist, East Carolina University

Dating material within a few decades to distinguish lost colonists from later settlers is difficult. Radiocarbon and other dating methods are not precise enough, and pottery styles don’t change uniformly over time and space.

For example, remains of a Border Ware pot found across the river in Edenton date to the late 17th century. “I couldn’t date artifacts between 1590 and 1630,” says Hume, a respected expert in colonial material. “Did someone keep something for six weeks or six years? It is very hard to know.”

Amid the new finds and trenches yet to be dug, archaeologists say they are hopeful new clues may yet crack the case of the missing colonists.

“There is still a lot of dirt to move,” says Swindell. And none of the groups have yet published detailed scholarly articles analyzing and cataloguing their discoveries.

“We still don’t know what happened, and we are waiting to be persuaded,” says Charles Ewen, an archaeologist at East Carolina University who is not part of either team. “I don’t think anything is off the table.”